By: Gcobani Qambela, South Africa, SSH Correspondent

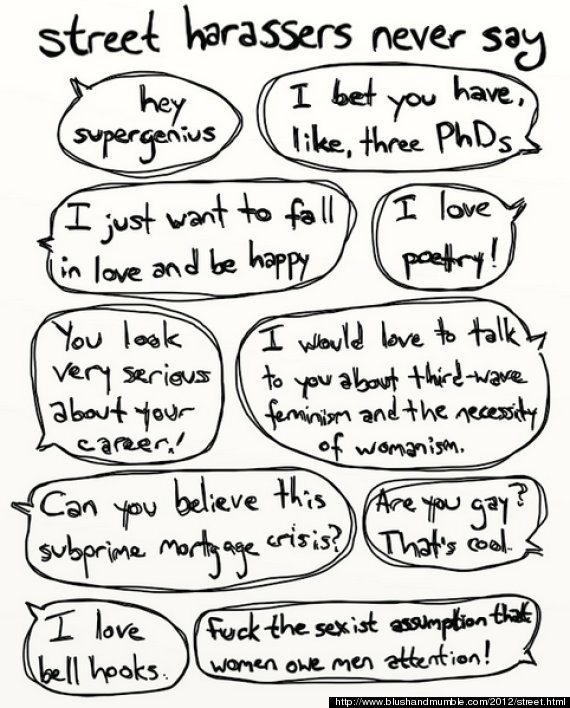

I recently read an interesting article in The Huffington Post titled “What We Wish People Would Say To Us On The Street”. The article covers the illustration by Norma Krautmeyer “which observes what people never say to women on the street.” This month I decided to talk to a small number of South Africans from across genders in various provinces in South Africa about the different ways they would like people to approach them in the street.

I believe street harassment in any form is unacceptable, but where necessary, how can men be better prepared to approach women in respectful and dignified ways in the street? What are the best ways to start a conversation with strangers across genders in a non-threatening way in the streets?

I spoke to gender activist and researcher, Rethabile Mashale, in Cape Town, in the Western Cape province of South Africa. She tells me that she has had her fair share of being subject to “catcalling and harassment” in the street. So what approach does she prefer when strangers, especially men approach her in the street? She says she has devised five basic alternatives. “The first is that a decent and genuine ‘hello’ and ‘how are you?’ which are followed by a genuine concern for whatever happens next” always work she says. Secondly she says “never lick your lips, or do a once over, over my body.

The person, thirdly, must look me in the eye instead of my tits” she continues. Fourthly she says while a clever joke can work, pick up lines are generally also unacceptable. She says lastly and mostly importantly “lead with getting my PERMISSION to engage in conversation, in fact, I would say that is the most important one” to get permission to talk and engage a person and quietly accept should she decline.

I also spoke to Amanda* in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. She told me she feels like street harassment is very degrading and that there is always a very “thin-line” between a stranger cracking a conversation and also at the same time harassing you. However the important distinction she made is that “Harassment is when I say ‘no’ and he doesn’t stop or if he feels the need to touch or say derogatory things to me.”

Tandokazi Mbopa, a university student in Port Elizabeth, in the Eastern Cape province, told me that she just does not want strangers approaching her in the street at all. This, she said, was born out of a horrible experience of being persistently harassed in the street. She told me that last year, she was walking and running late to school and a guy in a car kept hooting at her even though she ignored him. “He really didn’t get the hint ‘because he was driving next to me saying: ‘Oh, where are you going? Do you want a lift?’ as if I was going to get into that car after that hooting” she tells me.

Despite her declination to get into the car she says he refused to take a hint and kept driving slowly next to her saying, “Ooh, baby you’re hot. Baby you’re hot.”

“I felt like meat. The way he was looking at me. I was wearing track pants and a vest down to cover my butt… I wanted to change whatever was making him look at me like that and call me ‘sexy’” she tells me. “I don’t respect any guy approaching me on the street. I never will, unless if I’ve met you before – just not in the streets,” she concludes.

While these are only three interviews that I have included here, what emerged clearly from all the women I spoke to is that the key is consent and permission to approach and talk to women or anyone else in the street should be garnered clearly from the person who is being approached. If the women do not want to speak or engage then one should politely accept that. While Krautmeye’s illustration is encouraging, it is also important to remember that there are people with painful experiences like Tandokazi of dealing with harassers in the street even though the harassers probably thought they were saying something ‘nice’ to her. It is important therefore to treat even what appears to be ‘nice’ harassment with caution for it can also be traumatic for those on the receiving end. Consent and acceptance of a woman’s choice is thus critical in all cases, even if it appears that the guy is saying something that the woman would appreciate.

*The interviewee wished to remain anonymous.

Gcobani is completing his Masters in Medical Anthropology through Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. His research centres around issues of risk, responsibility and vulnerability amongst Xhosa men (and women) in a rural town in South Africa living in the context of HIV/AIDS. Follow him on Twitter, @GcobaniQambela.