By: Lisane Thirsk, Ottawa, Canada, SSH Correspondent

After reading SSH blog posts earlier this month about the history of street harassment in the U.S. (book review, author interview, and 100 years of activism), I was inspired to dig up some research I did a couple years ago for my master’s degree. For one assignment I went to the Archives of Ontario and uncovered criminal case files about street harassment around the turn of the 20th century.

According to historians, this period was characterized by “moral panic” in Canada. Social anxiety surrounded immigration, urban growth, and women’s shifting roles in public life.

My search at the Archives was guided by Karen Dubinsky’s Improper Advances: Rape and Heterosexual Conflict in Ontario, 1880-1929. I recommend this book to anyone interested in the history of street harassment – particularly Chapter Two on “The Social and Spatial Settings of Sexual Violence” in rural and northern areas of the province.

The legal records cited in Dubinsky’s book, as well as those I examined on microfilm reels at the Archives, provide vast documentation of sexual violence committed by strangers outdoors.

In rural communities, rape and sexual assault were often reported by women who had been attacked while walking through isolated farm fields. On small-town roads, women more often reported offences such as being chased, insulted or grabbed.

Just like in the U.S., street harassment was known as “mashing” at that time, and it was viewed as undesirable behaviour. The records show that these assaults didn’t just occur at night or when women were walking alone.

Panic emerged in numerous communities in Ontario. Mashers were stereotypically imagined as strangers in berry patches, tramps from Montreal, taxi drivers, and Indigenous men.

One of the most infamous predatory figures was known as Jack the Hugger, the nickname of a serial sexual assaulter (or more likely, several assaulters) appearing in the records from 1894 to 1916.

When confronted by a street masher, women were quite often assertive and resourceful. They defended their right to the street with defiant words, an umbrella, or by slapping the perpetrator.

Meanwhile, the prevalence of street harassment led commentators, including judges, to call for harsher punishment in the name of women’s freedom of mobility. And it was not uncommon for women – at least those who show up in the archives as “respectable” – to successfully pursue justice through legal avenues.

In her book Dubinsky reveals that the willingness of authorities to hold mashers accountable was due in part to the growth of the labour movement in Ontario.

As it became more acceptable for single women to migrate to towns and cities for jobs, scrutiny shifted to young lower-class men harassing female factory workers. Men’s public idleness and aggression were seen as threats to the values of self-control, restraint and productivity.

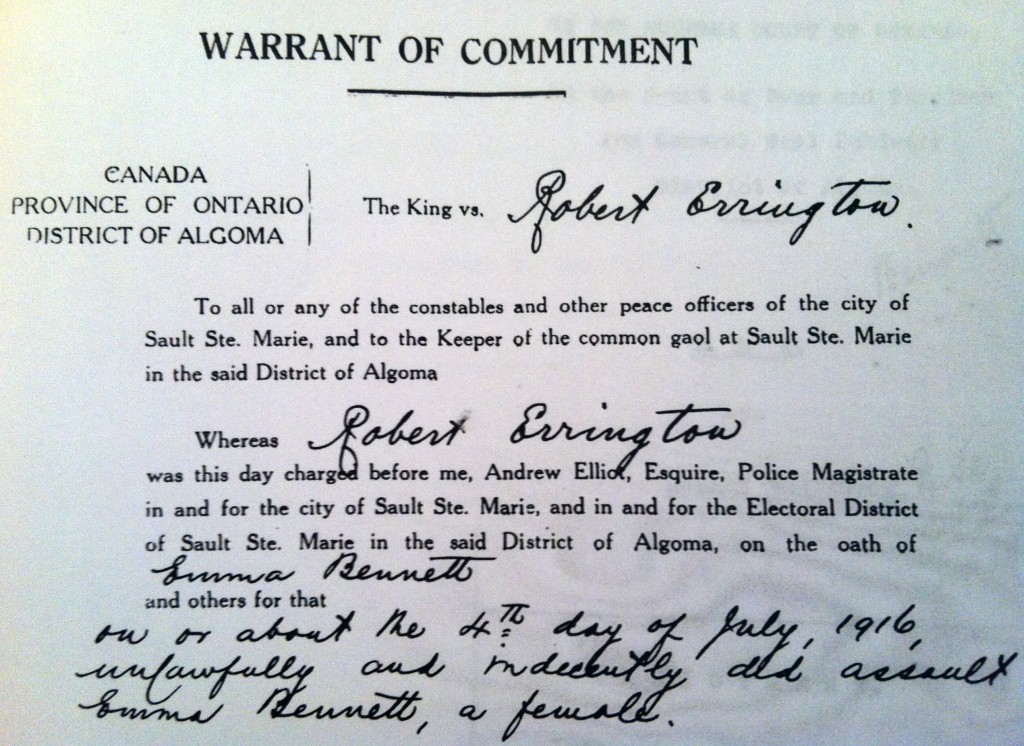

Below are the basic facts from one of the case files from Sault Ste. Marie that I examined at the Archives. It included statements from the complainants, the accused, and witnesses; and it illustrates some of Dubinsky’s conclusions about mashing in early 20th century Ontario.

* Around 7:30 a.m. in July 1916, Robert E. began following Emma B., a young woman who lived at a boarding house and was on her way to work at a tailor’s shop. Emma had been alerted to the Jack-the-Hugger stories circulating in her community, so she turned onto a busier street. Robert caught up to her, grabbed her hip, and said, “You would make good fucking.” He ran away, but Emma caught up to him and told him to keep his hands off her and to mind his own business.

* A few days later, Robert assaulted Louise P. around 5:15 in the evening. In her deposition Louise reported, “a young man caught hold of me by the bre[a]st … He turned around and put his hands down the front of his pants … I asked him what the devil he meant, and I started to follow him up, and then he ran.”

* In September 1916, Robert was charged with two counts of Indecent Assault on a Female. His defence focused on him having been steadily employed at the Steel Plant.

When we look back on the history of sexual violence, we tend to assume one of two things.

We either believe that in “the good old days” women were more respected in public and harassment wasn’t as explicit. Emma and Louise’s stories, along with many others I encountered at the Archives of Ontario, would suggest otherwise.

Or else we believe that as a society we’ve come a long way from the prejudiced thinking of the past. By reading between the lines in documents like Robert E.’s indictment, Dubinsky shows that it wasn’t always women’s wellbeing or principles of social equality that guided the prosecution of street harassers.

If we look carefully at today’s responses to street harassment – legal or otherwise – we might find many of these same patterns playing out.

Lisane works in the non-profit communications sector and supports local anti-street harassment advocacy through Hollaback! Ottawa. In 2012, she completed a Master’s in Socio-Legal Studies at York University in Toronto, where she wrote her Major Research Paper on gender-based street harassment. She holds a B.A. in Latin American Studies and Spanish from the University of British Columbia.