By Britnae Purdy, First Peoples Worldwide, Cross-Posted with Permission

In the past 20 years in Canada, over 600 mothers, daughters, sisters, grandmothers, cousins, aunts, and best friends have gone missing. That’s six hundred lives that have suddenly, mysteriously ended – no note, no motive, sometimes hardly even a clue, leaving behind questions, uncelebrated birthdays, motherless children, heartbroken partners, and emptiness. 600 Indigenous women have gone missing or been murdered, and often it seems as though nobody even cares.

Worse still? Though the publicly accepted number is 600, new data estimates that number to be closer to 900 women. And with the complications of underreporting, police mishandling of investigations, and other factors, it is likely the true number is much higher.

“There has been an awful silence around this,” says Otipemiswak/Michif Nation artist Christi Belcourt, of Espanola, Ontario. “There has been a silence by the government, by police and by dominant society; it’s as though Indigenous women’s lives aren’t considered important.”

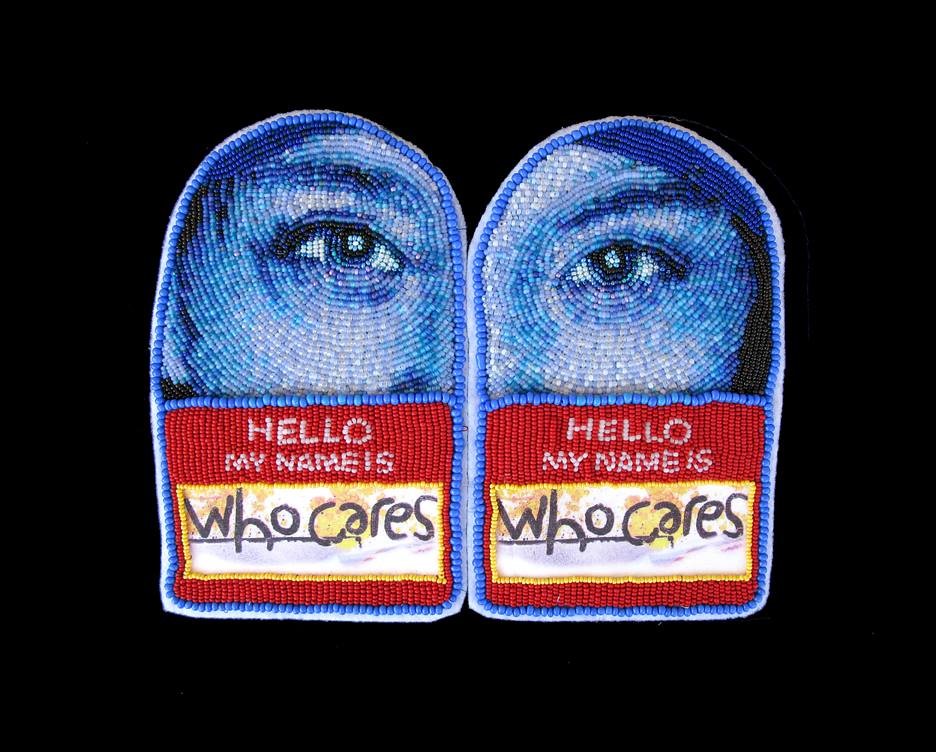

Belcourt’s newest art exhibit, “Walking With Our Sisters,” is hoping to visually demonstrate and bring attention to the hundreds of unsolved disappearances and murders of Indigenous women and girls across the United States and Canada. Belcourt’s idea is stunning and powerful – the exhibit features six hundred vamps, the top part of a moccasin, which is often the most decorated part of the shoe. Each vamp has been hand-beaded by a volunteer. Originally, Belcourt planned to create them all herself, but was daunted by the numbers. Within days of sending out a simple Facebook message, she had gotten commitments from over 200 people promising to help. The project’s Facebook page has grown to nearly 8,000 members, and the page is full of volunteers proudly showing off their exquisite beadwork. Some are veteran or professional beaders or members of beading groups; others are doing this for the very first time. But nearly all of them are dedicating their vamps to women that they have personally known that have gone missing, making this exhibit both a celebration of life and a collective outlet for mourning and remembrance. As Belcourt says, “each pair of vamps represents the unfinished life of one woman.”

To date, Belcourt has received 1725 hand-made vamps created by 1,372 volunteers. This exhibit is extremely interactive – the vamps are laid out on a 300 foot grey stretch of fabric, and visitors remove their shoes and walk alongside the vamps on red fabric. Tobacco will be available if guests wish to use it for prayer.

“The installation becomes a place for prayer,” Belcourt explains. “There is also sensory memory that people will take with them after leaving the exhibit. It’s not like walking into a space and just seeing work – you have to experience this.”

Indigenous women are 5-7 times more likely to die from violence than women of any other race, and experience 3.5 times higher rates of domestic violence and sexual abuse. Amnesty International, Canada, explains that the problem is multilayered and admittedly difficult to address, as “the scale and severity of the human rights violations faced by Indigenous women require a coordinated and comprehensive national response that addresses the social and economic factors that place Indigenous women at heightened risk of violence. Such a response needs to address the police response to violence against Indigenous women; the dramatic gap in standard of living and quality of life which increase the risks to Indigenous women; the continued disruption of Indigenous societies by the higher proportion of children put into state care; and the disproportionate rate of imprisonment of Indigenous women.”

Amnesty International recognize that the following systemic patterns contribute to the problem:

1. Racist and sexist stereotypes deny the dignity and worth of Indigenous women, and encourages some men to feel they can get away with violent acts of hatred against them

2. Decades of government policy have impoverished and broken apart Indigenous families and communities, leaving many Indigenous women and girls extremely vulnerable to exploitation and attack

3. Many police forces have failed to institute necessary measures – such as training, appropriate investigative protocols and accountability mechanisms – to eliminate bias in how they respond to the needs of Indigenous women and their families

The government has been largely unresponsive to the epidemic, and has only lately begun to show an interest in stopping in the rape and murder of Indigenous women. Grassroots organizations like Operation Thunderbird, frustrated with the lack of response from officials, have created crowd-source maps that allow people to compile information about missing loved ones.

“Women – who have been the future of the world in the form of its children – are being killed and tortured for rising up against those who oppress them, their children, and the earth we all share,” says the group. “Women that know about nurture and protection are being marginalized – told to sit down and shut up. Aboriginal women, who carry the wisdom, stories, and ancient teachings from long before the world became the civilized cesspool it is today, have little voice in their own governance. As people who care about others, we could only sit by and watch the horrors scroll in front of our eyes for so long before needing to take action. Operation Thunderbird is our contribution to the action of brave women all over the world who are Rising Up and demanding change.”

“Walking With Our Sisters” opened on August 23, 2013 at the Haida Gwaii Museum in British Columbia. The exhibit has thus far booked 28 exhibits across the United States and Canada, and plans to conclude in March of 2019 with a traditional ceremony in Kenora, Ontario.

“This project is about these women,” Belcourt concludes, “paying respect to their lives and existence on this earth. They are sisters, mothers, daughters, cousins, and grandmothers. They have been cared for, they have been loved, and now they are missing.”

Britnae is currently acting as the communications manager at First Peoples Worldwide, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting Indigenous communities, culture, and rights around the world. Britnae received her BA in International Affairs and Women’s and Gender Studies from the University of Mary Washington in 2013, and is now working on an MA in Global Affairs, with a specialization in Global Health, at George Mason University.