Cross-posted with permission from the author Patrick McNeil, our board member, from the Huffington Post

Late last week, the U.S. Office of Special Counsel found that the Department of the Army had discriminated against Tamara Lusardi based on her gender identity in a significant ruling that said Lusardi’s restricted daily movement “constituted discriminatory harassment under the guiding principles of Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act].”

At the same time, marriage equality is becoming the new normal, and the United States has suddenly become a nation where nearly two-thirds of same-sex couples live in a state where they can get married. Just this past Saturday morning, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that same-sex couples in six more states would receive federal benefits and have their marriages recognized by the federal government.

This is all very good news, but GLSEN’s annual school climate survey, also released last week, is a good reminder that – while LGBT Americans live in an increasingly evolving society – there’s still a long way to go.

At school, according to the survey, LGBT students really don’t feel safe. More than half (55.5%) of LGBT students feel unsafe because of their sexual orientation – and more than a third because of their gender expression. In the past month, almost a third missed at least one day of school because they felt uncomfortable, while more than a third avoided certain gender-segregated spaces (like bathrooms and locker rooms) for the same reason. More than two-thirds frequently or often heard homophobic remarks, and more than half heard negative comments about gender expression – like not being “masculine enough” or “feminine enough.”

LGBT students are particularly susceptible to verbal and physical harassment at school, and about half (49%) said they’ve experienced electronic harassment in the past year – such as via texting or on social media. What this all leads to is higher levels of depression and lower levels of self-esteem.

These findings, which are actually much improved from just a few years ago, are still very terrifying, given that schools are meant to be safe spaces where children spend a significant portion of their day. The findings are also very parallel with what we know about how LGBT people navigate and experience public spaces.

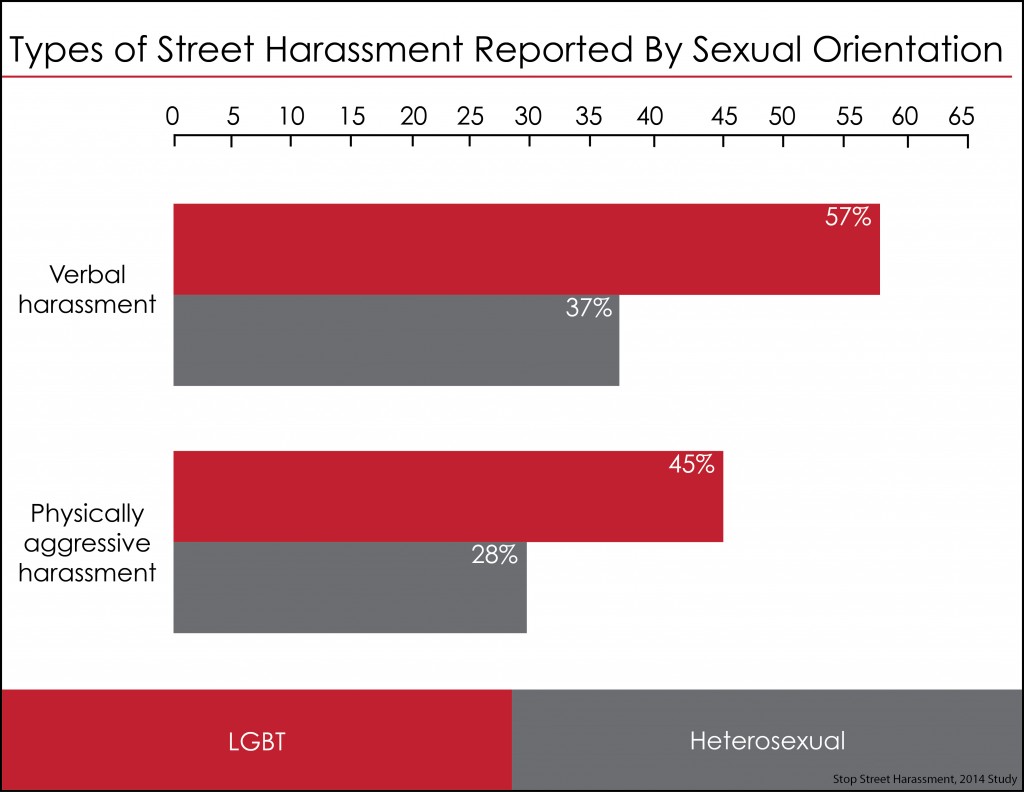

According to Stop Street Harassment’s (SSH) national study released earlier this year, LGBT people were more likely than straight people to report experiencing street harassment (both verbal and physical) – and it starts young. Seventy percent of LGBT people said they experienced it by age 17, compared to 49 percent of straight people (which is still very significant). In the same way that students in GLSEN’s survey reported avoiding certain activities because they felt unsafe, SSH’s study found that LGBT people were more likely to give up an outdoor activity for the same reason.

In my own research on the street harassment of gay and bisexual men – an admittedly much narrower group – survey respondents also reported high levels of avoiding specific areas or neighborhoods and crossing the street or taking an alternative route in order to sidestep unwanted interactions in what they felt were unsafe environments. In addition, 71.3 percent said they constantly assessed their surroundings when navigating public spaces.

That’s not healthy.

Whether at school or in public spaces, many LGBT youth don’t feel safe and continue to face disgraceful levels of discrimination (and some don’t feel safe at home, either). But when they enter the workforce, disadvantages persist.

In the absence of federal legislation like the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), it’s still legal in a majority of states to discriminate against employees simply on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity (even in some states where same-sex marriage is now legal). On the job, report after report notes the existence of persistent harassment and discrimination for LGBT people. And this is layered on top of pervasive race and gender discrimination.

This year, 50 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed, it’s certainly satisfying to know that the Act continues to guide favorable, groundbreaking rulings, like in the case of Tamara Lusardi. But we shouldn’t allow extraordinary advances to overshadow the amount of progress we still need to make toward full equality at school, in public spaces, in the workplace – and everywhere in between. Indeed, we’ve only just begun.