Katie Bowers, NY, USA, SSH Blog Correspondent

As a community educator, I work with a wide range of people. On any given day, I might spend the morning with adults talking about nutrition, the afternoon exploding homemade volcanoes with elementary students, and the evening working with high schoolers on a community change project. I’ve got a Batman-level utility belt of tools and tricks to use whenever I’m teaching. One of my favorite tools is comics.

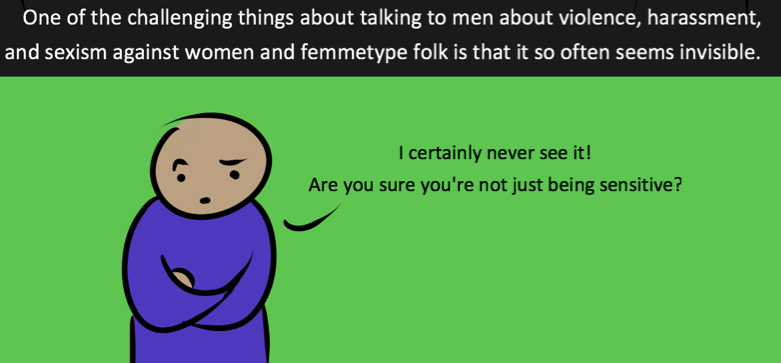

When we talk about social justice, we’re talking about complex systemic oppression, small, everyday injustices and big, in-your-face discrimination. We’re talking about oppressions that, like street harassment, are only experienced by a portion of the population. Other people may not even believe that a particular form of oppression is real. As a result, social justice organizers and educators are often trying to make the invisible visible.

Comics are highly visible by nature. Through rows of text on a screen or in a newspaper, comics ju mp out at us and demand to be read. They are usually simple to follow and understand. They are familiar and inviting, and can be made and distributed by anyone. Most importantly, they have a long history of activism – including calling out street harassment.

mp out at us and demand to be read. They are usually simple to follow and understand. They are familiar and inviting, and can be made and distributed by anyone. Most importantly, they have a long history of activism – including calling out street harassment.

The first editorial or political cartoon dates back to 1720, and there are cartoons documenting women’s struggles in everything from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire to the fight for universal suffrage. Comics have been talking about street harassment since at least the 1960’s. In a Fantastic Four title from 1963, Sue gets accosted on the street by a man remarking on her looks and – of course – telling her to smile. Being busy saving the city from peril apparently isn’t enough. She also needs to look perky while doing it. Fortunately for the Invisible Woman, her powers allow her to disappear – something many women wish they could do when they are catcalled.

In 1974’s Wonder Woman Sensation comics, it doesn’t matter that Diana is new to the planet and already cleaning up criminals. She immediately gets catcalled, with men ogling her and women calling her a “hussy”. In one particularly poignant panel, one of her male catcallers manages to objectify Diana and the two women insulting her. As early as 1974, comics were already showing how street harassment isn’t about how a woman looks or what she wears.

In 1974’s Wonder Woman Sensation comics, it doesn’t matter that Diana is new to the planet and already cleaning up criminals. She immediately gets catcalled, with men ogling her and women calling her a “hussy”. In one particularly poignant panel, one of her male catcallers manages to objectify Diana and the two women insulting her. As early as 1974, comics were already showing how street harassment isn’t about how a woman looks or what she wears.

These days, more and more cartoonists are offering their commentary and personal experience with street harassment. I believe that the reason for this is two-fold. Firstly, the advent of the internet has made it much easier for women (and for all people) to start producing and distributing comics. Cartoonists no longer have to break into newspapers or long-time comic publishers. They can do themselves, and they can write about their own lived experiences. Secondly, organizations like Stop Street Harassment, Girls for Gender Equity, Hollaback!, and many others have worked hard to get people talking about street harassment – and have they ever been successful. With everyone from Fox News, The Daily Show, and Playboy talking about street harassment, it makes sense that artists are weighing in as well.

Many of the current cartoons are dedicated to making street harassment more visible. Robot Hugs’ incredible long-scroll comic explores all sorts of different types of street harassment, as well the various things we say and do as a culture that make it possible to maintain a that harassment.

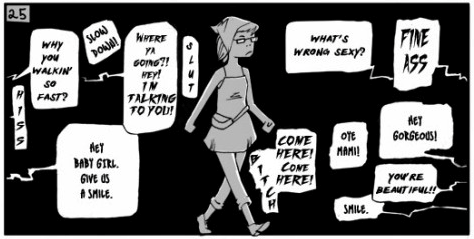

Lefty Comics also has a great example of what catcalling looks like on a day-to-day basis. Ursa Eyer’s Cat Call takes it a step further to show how a lifetime of regular harassment leads women to be constantly defensive when out in public, and how even that becomes cause for harassment.

Other anti-harassment comics are those that explore the supposed thought process used by the men who street harass. Kendra Wells’ comic looks at harassers and begs the question “What reaction did you expect to get?”

Some comics of this vein come from male allies who are asking their friends and fellow-Y-chromosome-havers the same question: why are you harassing women? Check out Matt Bors for a good example, or xkcd’s take on bystander intervention.

Finally, one of my very favorite anti-harassment comics is one that reminds us of the difference between a compliment and harassment. Ultimately, whether or not it is harassment is up to the person on the receiving end of the action. But as positivedoodles shows, there are a lot of ways to demonstrate your appreciation for others that aren’t derogatory, vulgar, or demeaning.

Comics are incredible tool for teaching social justice, and it’s fantastic to see so many artists speaking out against harassment. Do you have a favorite anti-harassment comic you want share? Send it to us on Twitter @StopStHarassmnt so we can share these tools with the world!

Katie is a social worker and community educator interested in ending gender-based violence, working with youth to make the world a better place, and using pop culture as a tool for social change. Check out her writing at the Imagine Better Blog and geek out with her on Twitter, @CornishPixie9.