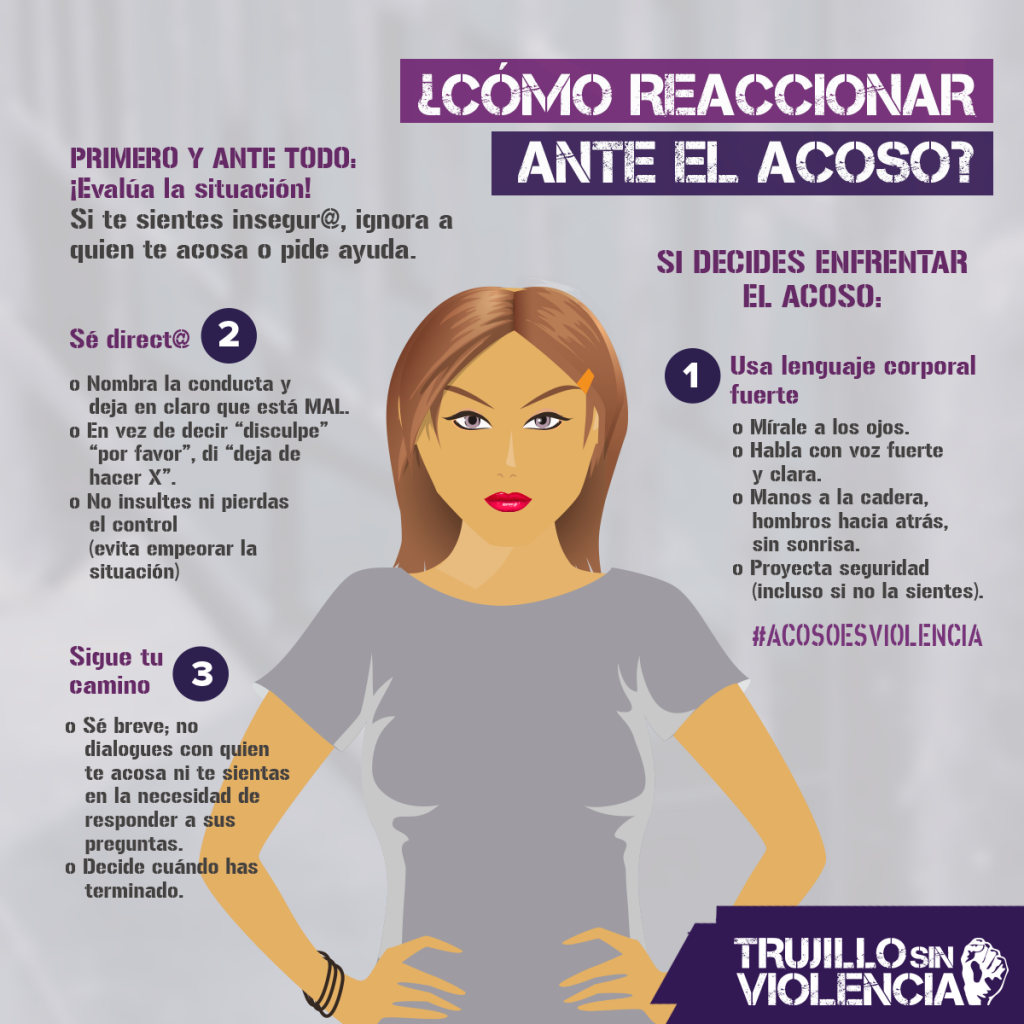

The new Peruvian group Trujillo sin violencia asked if they could adapt our “Quick guide to addressing street harassment” graphic for Spanish speakers. Of course we said yes and here is the end product! Excelente!

Making Public Spaces Safe and Welcoming

By HKearl

The new Peruvian group Trujillo sin violencia asked if they could adapt our “Quick guide to addressing street harassment” graphic for Spanish speakers. Of course we said yes and here is the end product! Excelente!

By HKearl

Katie Bowers, NY, USA, SSH Blog Correspondent

As a community educator, I work with a wide range of people. On any given day, I might spend the morning with adults talking about nutrition, the afternoon exploding homemade volcanoes with elementary students, and the evening working with high schoolers on a community change project. I’ve got a Batman-level utility belt of tools and tricks to use whenever I’m teaching. One of my favorite tools is comics.

When we talk about social justice, we’re talking about complex systemic oppression, small, everyday injustices and big, in-your-face discrimination. We’re talking about oppressions that, like street harassment, are only experienced by a portion of the population. Other people may not even believe that a particular form of oppression is real. As a result, social justice organizers and educators are often trying to make the invisible visible.

Comics are highly visible by nature. Through rows of text on a screen or in a newspaper, comics ju mp out at us and demand to be read. They are usually simple to follow and understand. They are familiar and inviting, and can be made and distributed by anyone. Most importantly, they have a long history of activism – including calling out street harassment.

mp out at us and demand to be read. They are usually simple to follow and understand. They are familiar and inviting, and can be made and distributed by anyone. Most importantly, they have a long history of activism – including calling out street harassment.

The first editorial or political cartoon dates back to 1720, and there are cartoons documenting women’s struggles in everything from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire to the fight for universal suffrage. Comics have been talking about street harassment since at least the 1960’s. In a Fantastic Four title from 1963, Sue gets accosted on the street by a man remarking on her looks and – of course – telling her to smile. Being busy saving the city from peril apparently isn’t enough. She also needs to look perky while doing it. Fortunately for the Invisible Woman, her powers allow her to disappear – something many women wish they could do when they are catcalled.

In 1974’s Wonder Woman Sensation comics, it doesn’t matter that Diana is new to the planet and already cleaning up criminals. She immediately gets catcalled, with men ogling her and women calling her a “hussy”. In one particularly poignant panel, one of her male catcallers manages to objectify Diana and the two women insulting her. As early as 1974, comics were already showing how street harassment isn’t about how a woman looks or what she wears.

In 1974’s Wonder Woman Sensation comics, it doesn’t matter that Diana is new to the planet and already cleaning up criminals. She immediately gets catcalled, with men ogling her and women calling her a “hussy”. In one particularly poignant panel, one of her male catcallers manages to objectify Diana and the two women insulting her. As early as 1974, comics were already showing how street harassment isn’t about how a woman looks or what she wears.

These days, more and more cartoonists are offering their commentary and personal experience with street harassment. I believe that the reason for this is two-fold. Firstly, the advent of the internet has made it much easier for women (and for all people) to start producing and distributing comics. Cartoonists no longer have to break into newspapers or long-time comic publishers. They can do themselves, and they can write about their own lived experiences. Secondly, organizations like Stop Street Harassment, Girls for Gender Equity, Hollaback!, and many others have worked hard to get people talking about street harassment – and have they ever been successful. With everyone from Fox News, The Daily Show, and Playboy talking about street harassment, it makes sense that artists are weighing in as well.

Many of the current cartoons are dedicated to making street harassment more visible. Robot Hugs’ incredible long-scroll comic explores all sorts of different types of street harassment, as well the various things we say and do as a culture that make it possible to maintain a that harassment.

Lefty Comics also has a great example of what catcalling looks like on a day-to-day basis. Ursa Eyer’s Cat Call takes it a step further to show how a lifetime of regular harassment leads women to be constantly defensive when out in public, and how even that becomes cause for harassment.

Other anti-harassment comics are those that explore the supposed thought process used by the men who street harass. Kendra Wells’ comic looks at harassers and begs the question “What reaction did you expect to get?”

Some comics of this vein come from male allies who are asking their friends and fellow-Y-chromosome-havers the same question: why are you harassing women? Check out Matt Bors for a good example, or xkcd’s take on bystander intervention.

Finally, one of my very favorite anti-harassment comics is one that reminds us of the difference between a compliment and harassment. Ultimately, whether or not it is harassment is up to the person on the receiving end of the action. But as positivedoodles shows, there are a lot of ways to demonstrate your appreciation for others that aren’t derogatory, vulgar, or demeaning.

Comics are incredible tool for teaching social justice, and it’s fantastic to see so many artists speaking out against harassment. Do you have a favorite anti-harassment comic you want share? Send it to us on Twitter @StopStHarassmnt so we can share these tools with the world!

Katie is a social worker and community educator interested in ending gender-based violence, working with youth to make the world a better place, and using pop culture as a tool for social change. Check out her writing at the Imagine Better Blog and geek out with her on Twitter, @CornishPixie9.

Diana Hinova, Sofia, Bulgaria, SSH Blog Correspondent

Sofia boasts several large parks: the South, West and North Parks (no joke on those names), Boris Gardens, and Hunting Park, for instance. For three weeks this autumn, the Runners’ Survey collected information from runners in Bulgaria about their perceptions of safety. The running community is growing here, thanks in part to initiatives like 5km Free Run which hosts organized runs every weekend in several Bulgarian cities. Running is a great, cheap activity that many people can rely on to keep in healthy shape – when the environment allows it. And since we seem to have the infrastructure, and the community, the Runners’ Survey aimed to investigate whether personal safety concerns prevent people from doing so.

Women runners cite personal safety much more often than men (22 percentage point difference) as a leading factor for the selection of where to run. For 12% of women runners this was the sole factor determining where to run (and for 5% of men runners), and not convenience to home or office, or safety from road traffic.

The forms of harassment described by the survey (since the general is not widely familiar in Bulgarian) included unwanted attention in the form of comments, whistling, gestures; attempts to touch; attempts by strangers to introduce themselves; a stranger following the runner; and physical assault. When asked specifically about instances of any of these forms of street harassment while running, 15% of men and 51% of women report having experienced it.

Logically, men runners use harassment avoidance strategies less frequently than women by orders of magnitude. Women runners most often rely on the selection of route and timing of their runs (31%) to avoid street harassment and other threats to their safety. Another common strategy is running with a phone and headphones (22%), although the role of headphones in runners’ safety is interpreted differently by some respondents:

“When running in areas that seem dangerous (eg. Borisov Garden in the dark), I take my headphones off in order to react more quickly if needed.” (w)

“I don’t wear headphones and I scan the surroundings when running” (w)

“I typically run with some friends and don’t pay attention to others in the area. If alone, I would be hesitant to run in an area with no one around or in parks at nighttime, even if there is lighting.” (w)

Women runners also often change their clothing choices (18%) and to a lesser degree rely on group runs, or carry self-defense aids like pepper spray, to avoid street harassment and more serious safety threats. These themes and strategies echo the recent #RWsafety twitter chat, where (mainly US-based) runners shared their experiences, concerns, and hope for change. An additional concern specific to Bulgaria turned out to be the sizable stray dog population.

It is important to consider the effect street harassment, which disproportionately affects the choices of women runners (and potential runners), has on women’s ability to equitably use of public space for healthy activity.

The results of the Runners’ Survey will be communicated to Sofia municipal and local government, officials in the Ministry of Physical Education and Sport, and other interested parties. The full summary of the Runners’ Survey results, along with graphics, can be accessed via the One Billion Rising Sofia Facebook page in English and Bulgarian.

Diana has a Master’s in Public Policy from Georgetown University and works as a consultant to INGOs. Follow her on Twitter @dialeidoscope or letnimletni.blogspot.com.

България: Да си тичаща жена

София се гордее с няколко големи парка: Южния, Западния и Северния, Борисовата Градина, Ловния Парк. тази есен за три седмици Анкета на тичащите събра информация от ентусиастите на бягане в България за усещането им за безопасност. Общността на тичащите се разраства, благодарение отчасти на инициативи като 5km Free Run, които организират безплатни седмични бягания в четири града. Tичането е страхотен, евтин начин за много хора да поддържат добро здравословно състояние – когато средата го позволява. Изглежда имаме инфраструктура за него, и изградена общност, за това Анкета на тичащите цели да разбере дали съображения за безопасност спират някой хора да се възползват от тази възможност.

Тичащите жени много по-често (22 процентни пункта) изтъкват личната си безопасност като водещ фактор при избора къде датичат от мъжете. За 12% от тичащите жени, това е единственият фактор определящ къде да тичат (и при 5% от тичащите мъже), а не удобство до дома и работата или безопасност от автомобилен трафик.

Формите на уличен тормоз описани в анкетата (тъй като цялостното понятие не е твърде познато в България) включват нежелано внимание изразено чрез коментари, подсвирквания, жестове; опити за докосване; нежелени опити за запознанства; следване; и физическо нападение. Запитани дали са били обект на тези проявления, 15% от мъжете и 51% от жените споделят че са срещали уличен тормоз по време на тичане.

Тичащите мъже прилагат стратегии за предпазване от нежелано внимание в пъти по-рядко от жените. Тичащите жени най-често прилагат внимание при подбор на маршрут и час за тичане (31%) за да избегнат нежеланото внимание и други опасности. Друга често срещана стратегия е тичането с телефон и слушалки (22%), въпреки че ефекта от носенето на слушалки при тичане предизвиква противоречиви мнения:

“При минаване през места, които ми се виждат опасни (напр. Борисовата градина по тъмно), свалям слушалките, за да реагирам бързо при нужда.” (ж)

“Не нося слушалки и се оглеждам докато бягам” (ж)

“Обикновенно тичам с компания и не обръщам внимание на околните. Ако съм сама бих се притеснила да тичам на обезлюдено място или в парковте особено на тъмно, дори и мястото да е осветено.” (ж)

Тичащите жени също често внимават в избора на облекло за тичане (18%) и в по-малак степен на тичането с придружител, или носене на защитни средства като спрей, за да избягват нежелано внимание и тормоз. Тези теми са паралели на дискусията в туитър #RWsafety, където тичащи жени (предимно от САЩ) споделиха свои преживявания, притеснения, и желания за промяна. Допълнителен фактор в безопасността на тичащите в България се оказват и бездомните кучета.

Важно е да си дадем сметка за ефекта, който нежеланото внимание оказва предимно върху жените, които тичат (или биха искали да тичат). Това е въпрос на равноправие да се ползват обществените пространства за лично здраве.

Пълно обобщение на резултатите: Анкета на тичащите 2014

By HKearl

Trigger Warning.

“A San Francisco man was stabbed and sustained life threatening injuries simply because he dared to ask a catcaller to leave his girlfriend alone.”

This is one of several stories from the past year where a father, boyfriend or male bystander stood up for a harassed woman and was hurt (or killed, as a father was in Chicago when he stood up for his teenage daughter). We have a SERIOUS problem on our hands that 1) street harassment happens and 2) that some harasses feel so entitled to women’s attention they will hurt anyone who challenges them.

Thank you, Ben, for speaking up and best wishes for a speedy recovery.

Siel Devos, London, England, SSH Blog Correspondent

By now, everyone has seen the video of a woman walking around New York for 10 hours and getting harassed over a hundred times.

But did you also know there has been a response in the form of a video of a woman walking through New York wearing hijab? The first 5 hours she is shown walking without hijab, experiencing harassment similar to the original video. However for the next 5 hours, when she does wear the hijab and niqab, she is miraculously not subjected to harassment at all.

The video says “you be the judge” implying that it is obvious to see that the only way to be free from harassment is covering yourself up. Once again, women are shamed and blamed – by both men and women – for bringing harassment upon themselves, merely by what they are or are not wearing. Once again people fail to acknowledge the real issue that is street harassment: the ingrained idea of entitlement and power over women and the fact that harassment is so normalized in both Western and Middle Eastern culture.

Victim blaming happens often when addressing sexual crimes and harassment, and even more in the cultural and social context of Islamic societies where women are seen as sexual creatures who are to blame for inciting men’s sexual urges. The idea of modesty and the concept of honour and shame regarding women’s bodies as a means of protecting women does nothing to solve the problem, rather it reinforces rape culture by always putting the blame on them.

The underlying meaning of this ‘modesty’ is that “good” women are those who cover up and belong to a man, “bad” women don’t cover up which implies that they are available to all men. In other words, respect for women depends mostly on their way of dressing as expected and imposed by men. Victim blaming and slut-shaming are very close related when talking about harassment. The notion of the male gaze becomes crucial here, and I very much agree with what the (anonymous) blogger behind A Sober Second Look says about this:

“What we didn’t notice was that regardless of whether we were measuring ourselves against a more or a less restrictive check-list determining “proper hijab,” we were nonetheless forever measuring ourselves in terms of an imagined male gaze, which we had internalized. We told ourselves that this had nothing to do with the male gaze, because what we were concerned with ultimately was obeying God. But coincidentally enough, the gaze that those check-lists had in mind was the male gaze. According to those check-lists, a woman has to always be aware if her clothing is “too” tight, “too” bright, “too” short, “too” fashionable, “too” eye-catching, “too” insufficiently Muslim… mainly, in the judgment of men—the generations of male scholars who had debated and determined these matters, and the male leaders of our community—and to a lesser extent, of a censorious and judgmental community generally.”

Going back to the message of the hijab video, “you be the judge” which implies that the hijab functions as a kind of invisibility cloak that magically protects against harassment and the male gaze. Problem solved then? Not really. How do you explain that 99.3% of Egyptian women experience harassment, when the majority of them wears the hijab?

The Qur’an and Hadith suggest that both women and men dress modestly in order not to incite sexual urges (an inherent natural aspect of human beings, both men and women). Maybe men who are shaming women for not wearing the hijab and saying this is required by the Qur’an haven’t read the Qur’an properly, as in the same chapter it is recommended that men lower their gaze. Other chapters in the Qur’an encourage men to respect women and treat them kindly. So why are we not addressing this blatant violation of Islamic doctrine? When are we going to focus on changing men’s behaviour and attitude instead of simply blaming women’s appearance and modesty?

Siel is a master’s student in Middle Eastern studies with a major in contemporary Islam at SOAS University in London. Find her on twitter and instagram under @mademoisielle.