Michelle Marie Ryder, USA, SSH Blog Correspondent

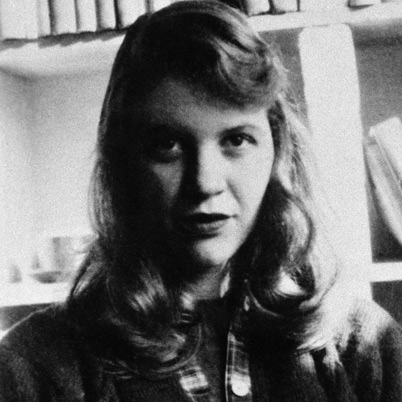

Despite her themes of feminism, there is no Sylvia Plath poem about street harassment. If you type “street harassment” into the search bar at two of the largest poetry databases (The Poetry Foundation and poets.org) you’ll get zero results. Type in “trees” or “love” and you’ll find hundreds or thousands of matching results.

It appears as if street harassment is not the subject of poetry. Which isn’t surprising, considering how historically male-dominated the literary world has been. Just like public space, cultural circles and high centers of learning are long-established male domains. Only within recent memory have women experienced some success in forcing the doors open, demanding a ‘room of their own’ in the literary world.

Still, I don’t think I ever expected to find a poem about street harassment by Sylvia Plath, despite the regularity in which her name surfaced when I talked to people about the subject. As both a literary giant and a feminist icon, I understood why Plath came to mind. But the dots, easy to connect, were still too few.

In truth, only very recently are enough dots beginning to appear and fuse intelligibly to bring the bigger picture into view. Thanks to our ability to disseminate our stories through modern technology, women from all ranks of society are speaking up and being heard, exposing the bigger picture of street harassment for what it really is: “a pattern of violence that constitutes a genuine social crisis,” writes Rebecca Solnit.

Despite the lack of search results at some popular websites, the poetic imagination is alive and flourishing. Survivors of street harassment are fighting back and sharing their experiences through the poetic medium. They are using poetry as a powerful tool to develop a vocabulary of dissent against gendered oppression in the public sphere. Surging with raw poetic insight and justified rage, these poets are transforming the streets by changing minds.

Being the digital age, this conversation is happening mostly online, on personal websites and social media platforms, among career artists and activists and ordinary folks alike. And because of its grassroots nature, it is expanding beyond the limited reaches of the white, cis, middle class female experience in order to embrace the experiences of the LGBTQIA community, lower-income people, people of color, and people with disabilities. Anyone who is not a wealthy, straight, white man is likely to endure public harassment at some point in their life.

Perhaps what’s most fascinating about this burgeoning genre of poetry is that it is dominated by spoken word: “performance-based poetry that focuses on the aesthetics of word-play and storytelling” (Wikipedia). This is in part because the literary establishment has yet to take street harassment as a subject of poetry seriously, but also – and more importantly – because spoken word is a natural fit.

Rooted in the oral tradition, spoken word has long served as a powerful vehicle for voicing dissent and agitating for social change. Poetry about street harassment is about moving beyond the individualistic poetic pursuit. It is about translating painful, self-aware moments into something larger, pushing poetic self-expression to answer to larger political realities in order to create a wider community consciousness – i.e. a movement.

It is about practicing freedom, even if we don’t have it yet. Change can and does start with a poem, even if your voice trembles. And now is the time to speak up. Visibility of the issue is at an all time high. The term “street harassment” has finally entered the popular lexicon thanks to the hard work of countless organizations and individuals.

Sylvia Plath may never have written a poem about street harassment, but it would be disingenuous of me to leave you with the impression that she was silent on the issue. She wasn’t. She suffered too, as much from the problem itself as from her own radical understanding of it, writing in her journal:

“My consuming desire is to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, barroom regulars — to be a part of a scene… all this is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always supposedly in danger of assault and battery. My consuming interest in men and their lives is often misconstrued as a desire to seduce them, or as an invitation to intimacy. Yes, God, I want to talk to everybody as deeply as I can. I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night…”

The limitations patriarchy placed on Plath’s life were obvious and unwelcome; catcalls, sexual solicitations and the underlying threat of assault policed her existence.

If street harassment is the shrinking of one’s world, poetry is its opposite.

Michelle is a freelance writer and community activist. She has written for Infita7.com, Bluestockings Magazine, and The New Verse News on a range of social justice issues, and shares her poetry regularly at poetrywho.blogspot.com.