Hannah Rose Johnson, Arizona, USA, SSH Blog Correspondent

Michel Foucault writes in Discipline and Punish (1975) that discipline is used to control entire populations through organizing space and the self-policing of individuals. For instance, he writes extensively about the panopticon—an architectural design of a prison, where a tower sits high in the middle of a circle of cells and while guards can see out of the tower, prisoners cannot see in. Without telling if a guard is or isn’t in the tower, prisoners are forced to police their own behavior and the behavior of others because, what if the guard is in the tower and watching? The architecture of communities plus the management of people is a way in which power is exercised. Power is a producer of reality that includes objects, rituals, examinations, individuals, “norms” and truths. He says, on the panopticon: “Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals which all resemble prisons?” (p. 228).

Michel Foucault writes in Discipline and Punish (1975) that discipline is used to control entire populations through organizing space and the self-policing of individuals. For instance, he writes extensively about the panopticon—an architectural design of a prison, where a tower sits high in the middle of a circle of cells and while guards can see out of the tower, prisoners cannot see in. Without telling if a guard is or isn’t in the tower, prisoners are forced to police their own behavior and the behavior of others because, what if the guard is in the tower and watching? The architecture of communities plus the management of people is a way in which power is exercised. Power is a producer of reality that includes objects, rituals, examinations, individuals, “norms” and truths. He says, on the panopticon: “Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals which all resemble prisons?” (p. 228).

Is it surprising that sexual violence resembles white supremacy, compulsive heterosexuality, heteronormativity, neoliberal economics which all resemble sexual violence? (Please refer to my previous article Police Violence is a Form of Street Harassment). We live in a culture of discipline, watching ourselves and others, which is shaped by an architecture of domination. Sexual violence and oppressive systems are about power and control.

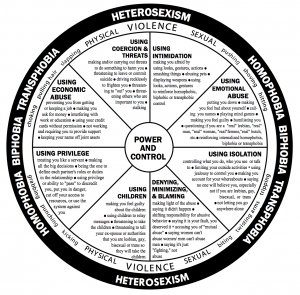

This month I have been thinking about intimidation in public spaces. On the Power and Control Wheel, which is used to identify patterns of physically and sexually violent behavior within intimate partner violence, there is a section for intimidation. Wheels differ from varying degrees, but generally intimidation highlights: placing partner in fear by looks, actions, and gestures; smashing things; destroying property; displaying weapons; sending frequent, unwanted messages and expecting the partner to respond immediately; and stalking. What I’m interested in exploring is the link between intimidation, control and power. That the use of intimidation, the behavior, is a performance of control and shaped by experiences of domination.

When I think of public spaces, I think of streets, I think of the commons, parks, I think of state and county buildings, I think of school systems and universities. I think of signs and lights and billboards and advertisements. I think about how power is exercised in ways that allow communities to organize themselves based on interlocking systems of oppression. When I think of public spaces, I think about the social contract that binds most of us together.

Social contract theory refers to the things we give up in order to come into public spaces; moral and political obligations, like agreeing not to take matters into one’s own hand and put faith in a legal system. Social contract theory explains how some people are locked away from public space and other people are not recognized even though they are here all the time, on the basis of race, gender identity, class status, sexual identity, HIV+ status, and unregulated labor.

I’d like to explore reproduction coercion within the context of intimate partner violence and expand the conceptual understanding. Reproductive coercion is forcing a partner into pregnancy when they do not wish to be pregnant, or forcing a partner to have an abortion when they wish not to. Reproductive coercion includes the murder of Native women during colonization so that an entire race of people would be wiped out. It includes the raping and forced pregnancies of Black women during slavery in the US to birth an entire disposable and exploited labor force (please read Incite! Dangerous Intersections).

And then there is reproduction in the performative sense- the reproduction of social roles and systems. In this instance, intimidation. If you play the intimated, you are the role that is the reason of power and control. Intimidation is white supremacy, compulsive heterosexuality, heteronormativity, and neoliberal economics. These systems of oppression feed an exercise of power, from anti-abortion billboard messaging to construction of the welfare queen—the image of the sexually immature Black mother who is both draining government assistance and creating poverty. Reproductive livelihoods are constantly threatened and queered.

In public we are surrounded by intimidation and it is a tactic of sexual violence. In the expanded understanding of imperfect victims (again, please refer to my article Police Brutality is a Form of Street Harassment), we see that not only is street harassment bound to sexual violence, it’s also dependent on reproducing instances and interactions of intimidation. So that when some people can control other people by a look or a gesture, or a certain kind of eye contact, power is running through the exchange. And actions, looks and gestures exist between partners, strangers, and the public/private. The look/gesture is the panopticon of intimidation.

It is the self-policing and submission for survival in violent relationships and interactions. Intimidation is a currency. It is intertwined with reproducing fear—in the context of street harassment it is the fear of harassers, from catcallers to police officers. Fear instills control, a conduit for power. And power, of a sexually violent nature, is sustained through systems of white supremacy, compulsive heterosexuality, heteronormativity and neoliberal economics.

Hannah Rose is writing from Tucson, Arizona and Lewiston, Maine (US) as she transitions from the Southwest to the Northeast for a career in sexual violence prevention and advocacy at the college level. You can check her out on the collaborative artistic poetic sound project HotBox Utopia.