Eve Aronson, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, SSH Blog Correspondent

The events in Paris last week, just a few hours drive from Amsterdam, were tragic and appalling. They also represent an extreme form of a familiar foe.

The Paris shooters targeted people in public venues—sports stadiums, restaurants and concerts—dictating their movement and using violence to carry out their agenda.

What such a choice in venues and tactics makes clear is that the perpetrators targeted spaces designed for public use and leisure and used violence towards people they did not know within these spaces.

We can therefore look at the events in Paris as examples—albeit extreme ones—of the broader power structures that define how safe people feel in public spaces.

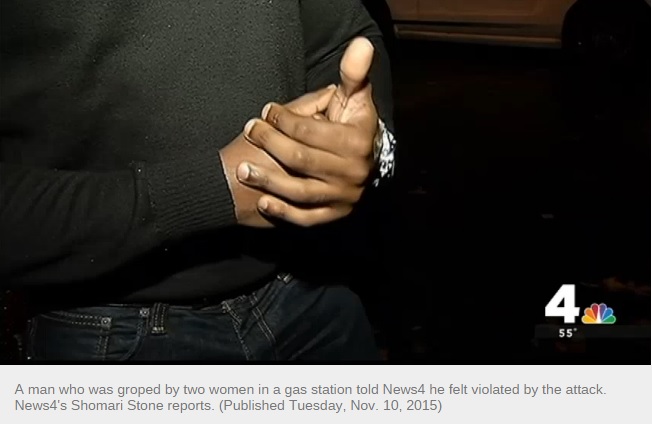

Not unlike a man groping or catcalling a woman on the street, the incidents in Paris show how important it is to understand seemingly mundane ‘everyday’ street harassment incidents as part of broader notions of freedom and safety in public spaces.

You might be thinking: Wait a second. That’s a bit of a stretch. Street harassment is, for one, typically gendered (e.g. a man catcalls/whistles at/gropes a woman), whereas the Paris events were not.

That is a valid point to raise and indeed, the Paris events were not explicitly gendered (although they do have implicit echoes of links between terrorism and masculinity that have been raised in relation to previous violent attacks in public spaces).

However, there are a few important connections to highlight that bring these issues closer together than you might expect.

But before I do, I want to note why I am taking the time to do so. By showing how different and seemingly unrelated forms of violence within public spaces connect, my hope is that better, more lasting and enduring solutions can be found to a larger number of problems that affect people in public spaces. In addition to finding better solutions, underlining the similarities among these issues can also lead to more resources and brains available to prevent them in the future. But I digress.

One main connection between the incidents in Paris and everyday street harassment are that the feelings of powerless, confusion and fear that were evoked last Friday were the same feelings that people in Amsterdam, for example, reported feeling while and after they were harassed.

And, at least for the short-term, the feelings of apprehension that many people in Paris are feeling when they step out into the public sphere is not so dissimilar to the feelings expressed by people as a result of their experiences with street harassment in Amsterdam.

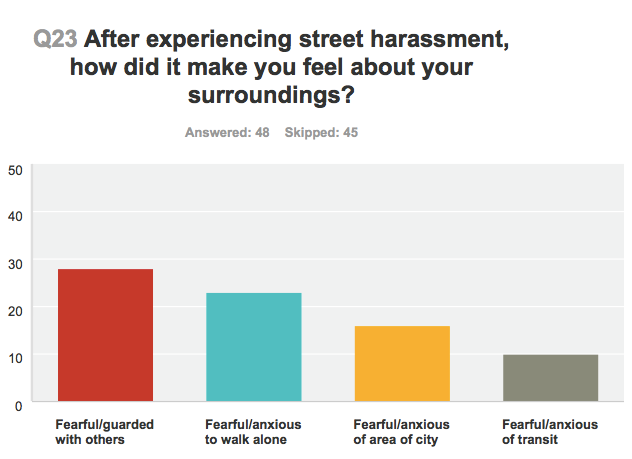

Below is a chart of some of the primary feelings about their surroundings that people in Amsterdam reported after experiencing various forms of street harassment:

A look on the conversations happening on Twitter about the Paris events reveals a similar spectrum of emotions. What this shows, is that in order to more fully understand and fight against issues like street harassment and violent attacks in public spaces, we have to start making connections between different manifestations of impeding or restricting movement within public spaces.

By doing this, we can start to see broader power structures emerge that reveal why these incidents occur and the factors that drive people to be physically or verbally violent towards others they do not know within different public spaces around the world.

The majority of reasons that people in Amsterdam, for example, think that their harasser(s) did what they did is that they believe their harasser(s) want to fit in with others in some way and to be accepted and applauded for their actions. The second most common reason people cited that was that they believed that their harasser(s) thought it was the ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ thing to do.

The fact that many perpetrators (street harassers or others) are motivated by group acceptance and by what they think is normal are just more of the many commonalities between issues like street harassment and other forms of violence in public spaces.

In a time where people are increasingly fearful, anxious or weary of moving through public spaces—whether because they do not want to be catcalled or groped, or whether because they do not want to be harmed or attacked in another way—it is absolutely essential that we make it our priority to examine the links between different forms of violence in public spaces more closely.

Looking at these links and using them to our advantage in the fight against street harassment and against violence in public spaces will lead to more informed policies, more helpful solutions and to more individuals feeling safer in public spaces. So what are we waiting for?

You can find the full analysis of the Amsterdam survey results here or by contacting Eve at evearonson@gmail.com. Follow Eve and Hollaback! Amsterdam on Twitter at @evearonson and @iHollaback_AMS and show your support by liking Hollaback! Amsterdam’s Facebook page here.