Tharunya Balan, Bangalore, India, SSH Blog Correspondent

Trigger Warning

The 2012 case of the young woman who was fatally raped and assaulted on a bus in the Indian city of Delhi led to a number of decisions made at the State and Central levels to address violence against women, including several new laws against rape and sexual assault. The new laws include specific mentions of sexual harassment, voyeurism and stalking as punishable offences.

The 2012 case of the young woman who was fatally raped and assaulted on a bus in the Indian city of Delhi led to a number of decisions made at the State and Central levels to address violence against women, including several new laws against rape and sexual assault. The new laws include specific mentions of sexual harassment, voyeurism and stalking as punishable offences.

The publicity and international attention around the issue has led to more open conversation on the subject and encouraged more (mostly educated) women to report sexual assault and harassment. Unfortunately, passing laws to criminalize behaviour does little to change the prevalent rape culture and attitudes towards women held by much of the population. Even judges in other countries seem to assume that Indian culture means men simply do not understand boundaries and so cannot be held accountable for their actions.

In May of 2015, Amnesty International India approached the feminist magazine The Ladies Finger about their upcoming Ready to Report initiative, aimed at making it easier for victims of sexual harassment and assault to report incidents to the police. The online magazine then threw their doors open to people who had experienced sexual assault or harassment, and asked if they had tales to tell.

The stories published (a woman assaulted in a car, a woman molested by a friend she was visiting, a woman stalked by an old classmate, a woman molested on the street by a stranger, a team of journalists stalked and harassed by a stranger) include examples of the victims being interviewed in front of their attackers, of them being forced to recount the most intimate details of their assaults in front of a station full of curious policemen, of being browbeaten into recanting or rewriting their stories, and of their being treated as overreactions to minor annoyances, and the police taking it upon themselves to mete out justice as they saw fit.

The campaign also included a twitter hashtag that paints a depressing picture of the narratives that surround victims and stories of sexual assault in the country. Women are hesitant to speak up for a number of reasons, ranging from the fear of reprisals, the social stigma around sexual assault, the fear of being slut shamed for their choices, the stress of filing and following reports while fearing more harassment at the hands of the police force, the fear of negative media attention, and the fear of not being supported by friends and family, and the horror that surrounds medical examinations.

The founder of The Ladies Finger, Nisha Susan writes:

“The variables that affect whether an Indian woman’s claim is taken seriously by the police range considerably, from class, caste, the site of the assault, to the time of day. The more familiar the complainant was with the assaulter/ rapist/ stalker the less likely she was to successfully register a case. Our findings backed up results from the more rigorous studies undertaken by activists: in the legal system, you are likely to fare better if you have been violently assaulted by a working-class stranger in a public place.” (emphasis mine)

This only underscores the fact that marital rape is not a punishable offence, or indeed, a term recognized by the law at all, and it explains why so many reports of stalking are ignored or not taken seriously.

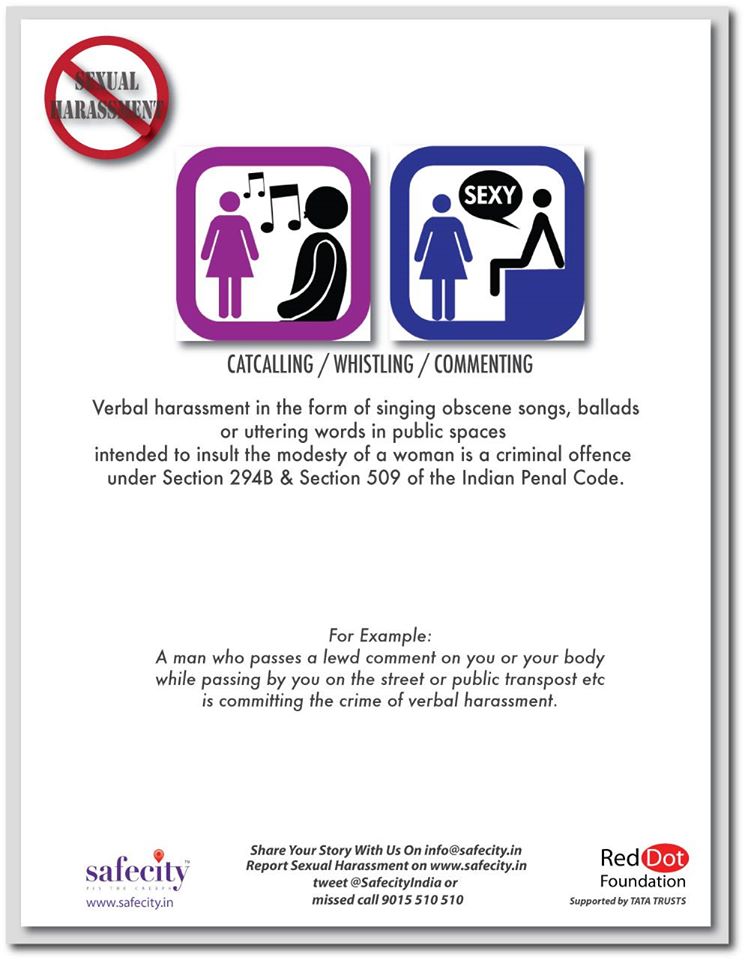

There is a lack of genuine discussion around the way women and women’s bodies are perceived in this country. The original text of the law (section 354 of the Indian Penal Code) defines as criminal the “assault or criminal force to woman with intent to outrage her modesty”, and it is this idea of “modesty” in the India context that is still such a sticking point. It is this idea that lies at the heart of the victim blaming, the slut shaming, and the dehumanizing treatment of rape and assault victims when they do come forward.

It is not just female victims who suffer under our archaic ideas of modesty and bodily autonomy. The sections of the Indian Penal Code that refer to rape are not gender neutral, and they do not acknowledge male victims of rape. There is something deeply embarrassing about a country whose leaders and whose laws are the equivalent of an ostrich sticking its head in the sand and pretending that what it sees does not exist. Treating sex as a taboo, refusing to understand the spectrums of gender and sexuality, ignoring the contradictions between what is portrayed in our media and what is taught to our children in schools and homes, and

What we are in dire need of in our country is real sex education: real conversations on consent and real understandings of the ways in which someone’s body and person can be violated by another’s actions.

Tharunya is an urban planner and architect with a passion for issues of social, environmental and spatial justice, including the gendered ways in which urban spaces are designed and function. She has a bachelor’s degree in architecture and a master’s degree in City and Regional Planning from the Georgia Institute of Technology, where she will be returning to obtain a degree in Geographic Infomations Systems Technology later this year.