Elaine Crory, Belfast, Northern Ireland, SSH Blog Correspondent

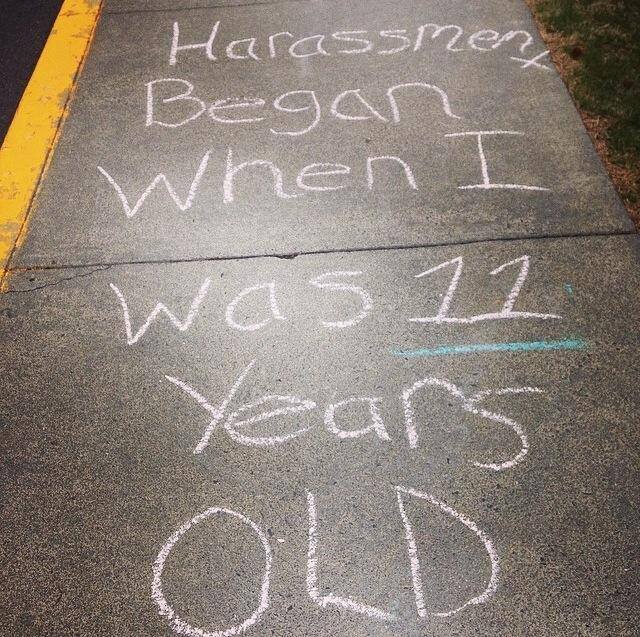

In survey after survey, women tell us that they begin to experience street harassment at a young age; many as young as 12 years old, almost all by the age of 18. In a world where so much divides us, this is something that is almost universal for young women.

In survey after survey, women tell us that they begin to experience street harassment at a young age; many as young as 12 years old, almost all by the age of 18. In a world where so much divides us, this is something that is almost universal for young women.

The evidence for the harm that street harassment does is enormous, too. Young women learn to text friends to say they got home safe, to keep keys between their fingers or mace in their bag, to shrink away from large groups on the street or in public transport. They turn up the music on their headphones to drown out catcalls, or pretend to talk on the phone, or lie about imaginary boyfriends – because some men will respect another man’s supposed territory before they will heed a woman’s “no”.

But the effects goes beyond behavioural changes to avoid harassment. The impact on women’s sense of independence, on her comfort in her own skin is hard to gauge in numbers, but we hear testimony of it again and again, via resources like Stop Street Harassment, Hollaback!, and the Everyday Sexism Project. Teachers and parents see young women shrink into themselves and become less outgoing and confident, less willing to go out by themselves perhaps, more self-conscious of showing legs and bellies even in the height of summer. Projects like SSH, and the online realm generally, are invaluable resources for sharing stories and experiencing solidarity, but somehow the need to find support on the internet when surrounded by women – mothers, grandmothers, sisters, friends – who have been through the same ordeals is indicative of the greatest harm done by street harassment. It fills us with shame. It teaches us that it is our fault, our just desserts and as inevitable as death and taxes.

When we are still children in so many ways we learn that we are subjects to be observed, categorised and consumed by men. We are objects to be desired or to arouse disgust. At all times when we are out in public, we are inviting judgement and appraisal. Young men become consumers and arbiters of taste. It is no wonder that so many men take that supposed right to all other areas of their lives and that so many of us tolerate it, after all even the President of the USA grades women from 1 to 10. We knew this, and yet the majority of white American women voted for him. It’s unremarkable. It’s just how the world is, right?

I recalled in my last piece for SSH that my first experience of street harassment was being told that I was ugly, and that I immediately believed my harasser. I was ashamed of my own obviously strikingly ugly appearance, disrupting a man’s peaceable walk through the town on an unassuming afternoon. The sense of shame was so strong that I was in my 30s before I told anyone my experience, and as I did so I felt a strange lump on my throat and tears come to my eyes. After all the years that had passed in between, and even after the feminist texts and work on anti-harassment groups, the shame and humiliation is still there. It took a while before I realised that I felt much the same about the times I’d been cat-called, touched or groped, flashed and leered at. So different and yet so similar, because they all were rooted in the fact that we all grew up in a society that sees women as consumables and men as the consumers.

That is the real and frightening impact of street harassment. It is at the coalface of everyday sexism, the first clumsy instrument of rape culture, the insidious infection that makes so much of the sexism and misogyny that we encounter seem somehow natural and inevitable. And it starts alarmingly young, perhaps even younger than the figures can capture. I was 13 when I was told that I’m ugly by a stranger, and also 13 when a much older man furtively rubbed his erection against me on a bus. Legally and socially, I was a child – albeit one with breasts. Why had I already internalised the shame? Because it permeates all social interactions.

I walk my 5 year old home from school, and it is striking how often people – generally men – comment on her appearance. Usually it seems that she doesn’t notice. Once, though, an older man wanted to give “the lovely child” a coin. She recoiled and hid behind my coat, and his reaction was to curse, toss the coin towards me, instead, and to reach around me to tousle her hair. She cried in anger and shock most of the way home, and I felt choked with both anger and fear for the future, because this is how it starts. This is why I accepted verbal abuse at the age of 13, and now I worry that she will, too. We walk on the other side of the road now, more often than not, and I hate that fact.

Elaine is a part-time politics lecturer and a mother of two. She is director of Hollaback! Belfast, co-organises the city’s annual Reclaim the Night march, and volunteers with Belfast Feminist Network and Alliance for Choice to campaign for a broad range of women’s issues.