Yasmin Curzi, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, SSH Blog Correspondent

In 2006, the Legislative Assembly of the State of Rio de Janeiro approved a law which enacted segregated areas on public transport for women, commonly known as “pink carriages.”. According to the memorandum of the law, the measure would serve as a remedy in order to avoid severe sexual harassment cases during rush hours on the city’s metro. It enunciates that this measure serves as an immediate remedy, “because the scenario of recurrent gender violence in public transportation is a problem difficult to overthrow.” Also it has few costs for the State or the concession-holder, so the implementation can be faster than other possible measures.

In effect, women who suffered from abuses would feel welcoming in this “special” spaces – a symptom of the institutional mistreatment directed to them. There are some narratives that corroborates with this approach, but the discussion about the real effectiveness of the law is far to be settled. In this article I’ll try to point some of the controversial topics concerning this public policy.

1. Enforcement: Supervision of women-only carriage is made by the metro guards, only on a few platforms – usually the ones located in richer neighborhoods. The result is that men often disobey the law, specially when the subway is crowded. Also, most of the guards are men and frequently present misogynistic behaviors toward women who suffered abuse in the subways. In most of the cases, they are insensitive about women’s issues and unprepared to deal with these occurrences. Often it results in a double-violation: women are slut-shammed, offended or neglected when try to make a complaint. And the guards themselves also harasses women, usually by leering or starin

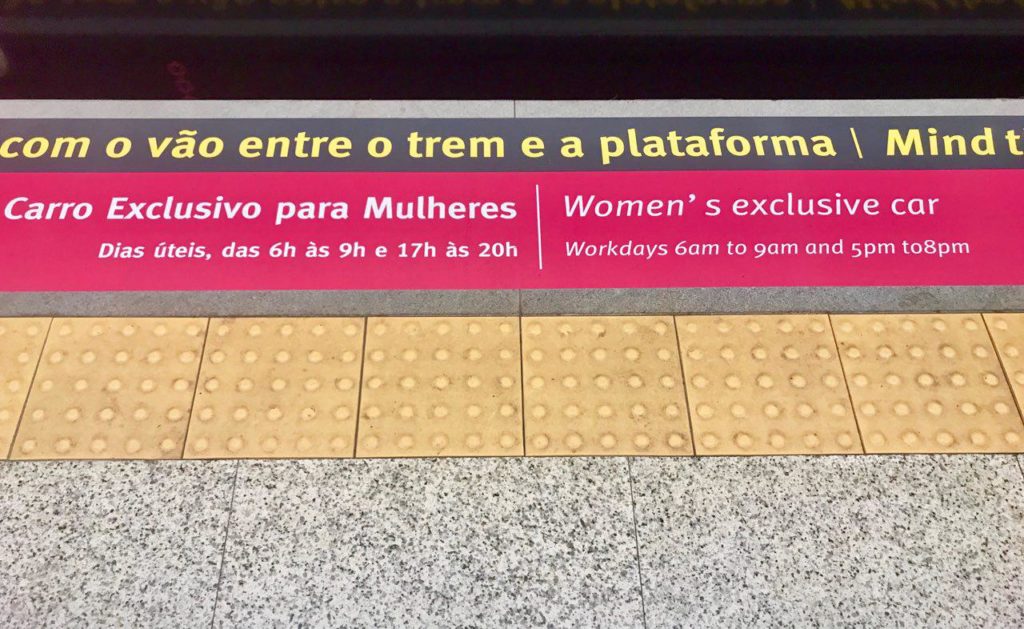

2. The law’s definition of “rush hours”: “Rush hour” is settled by the law as being “workdays 6h a.m. to 9h a.m. and 5h p.m. to 8h p.m.”, but the use of the subways increased severely in the last decade. Therefore, “rush hours” are dynamics nowadays. A college student reported to me that she suffered harassment and abuse on a Saturday afternoon. The subway was crowded and a white blond guy started to stare at her breasts, stopped in front of her and masturbated himself. Then, she ran scared and chose not to make a complain. Stories of women that decided not to report harassment and other violations are recurrent, because, not only are institutions often hostiles toward those victims, but also society normalizes these behaviors.

3. LGBT concerns: One problem of the law is that it essentializes women as an homogenous group, excluding lesbian, bissexual and transexual women. For these groups, the space doesn’t bring the same feeling of welcomeness that it does toward cisgender and heterossexual women. A lesbian woman reported to me that, when she is in the companion of another girl, before going to college at 7h a.m. (considered as a rush hour by this law), the staring of other women made her feel like she is a “circus attraction”. The women’s car is, therefore, designed for one specific group of women, nurturing the normalization of conducts in a heteronormative society.

4. It is a merely makeshift: The law memorandum itself affirms that this measure is a quick response to reduce violence towards women. However, it’s possible to assume that public power chose the easiest path. By segregating spaces by gender, the State gets rid of its duty to address the real causes of sexism with more profound and long-term measures, such as education campaigns, in order to change the perception of women’s body as a public property.

5. It corroborates victim-blaming: Another issue of the law is that it implies a perception that if a woman isn’t in the women’s car in a “rush hour”, she is responsible for the harassment suffered. Victim-blaming is recurrent in other abuses/harassment situations and usually materializes in thoughts like “what was the victim’s wearing” and “what was she doing in the street late of the night”. Segregated spaces also spreads the idea that if a woman wasn’t in the women’s car, then she “wasn’t taking the necessary precautions in order to avoid risk situations”.

The discussion about this law is in dispute even inside the feminist’s movement. There isn’t a consensus about its real effectiveness and what other measures the State could implement in order to deal immediately with sexist violence in the public transportation. However, it’s pacified that short-term measures aren’t able to solve these issues in a profound way, thus, State should also institute awareness campaigns and public policies that treat sexism in its structural roots and not only by focusing in its surface results.

Yasmin is a Research Assistant at the Center for Research on Law and Economics at FGV-Rio. She has a BA in Social Sciences from FGV-Rio and a Master Degree in Social Sciences from PUC-Rio, where she wrote her thesis on street harassment and feminists’ struggles for recognition.