Yasmin Curzi, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, SSH Blog Correspondent

In order to address sexual violence, the first and necessary step is to identify what is violence. This involves the engagement of government and civil society as a whole.

In order to address sexual violence, the first and necessary step is to identify what is violence. This involves the engagement of government and civil society as a whole.

In 2013, Avon Institute launched a report showing that some violent behaviors are not seen as such. Even though 52 million Brazilian men acknowledged what constitutes domestic abuse or violence against a female partner, 9.4 million admitted that they committed violence in their own personal relations. This study also showed that when the violence is detailed, the positive answers of respondents increases, meaning that there are some kinds of behaviors that are not comprehended as being violent by their perpetrators.

Another contradiction is the fact that 41% of Brazilian population knows a man that was violent with at least one of his female partners. However, only 16% admitted that they were violent with the actual or ex-partner and 12% admitted violence against the current female partner. The most common type of violence that appeared in the report was verbal insult, with 53% of the men admitting to it. This data can have a bias since it’s generally not as shocking as forcing the partner to have sex, what only 2% of the male respondents admitted to have done.

The report also shows that there’s no differentiation of class when it comes to general violence against women. Even though poor and Black women suffer with more lethal and sadist behaviors, around 50% of the male-respondent in every social class (high, medium and low) admitted that they had committed violence.

Male-respondents also affirm that the violence perpetrated by them weren’t isolated cases: 87% of the men who had once insulted their female partner, insulted them more than once, and the average is that it happens around 21 times per man; also, 74% of the men who had once forced sex, forced it more than once, and it happens around 5 times per man on average. Another shocking data point is that 37% of male respondents said that the law against domestic abuse makes them disrespect women more.

The importance of social engagement to stop violence against women is evident when we see that violent men have grown with abuse in their homes. Traditional roles, therefore, are their references. Male socialization is violent and often boys are taught not to show their emotions, except anger. Family and school are often environments that enhance toxic masculinity. The majority of the male respondents don’t see in their fathers a figure of care (only 14%), but only in their mothers (74%). Also 81% of the men who committed violence were beaten in their childhood.

The Internet creates the possibility for the victims to express their individual stories of abuse and violence. This is a big step for transforming culture since most violent behaviors are not seen as such, neither by the perpetrators nor by the victims, as the report shows.

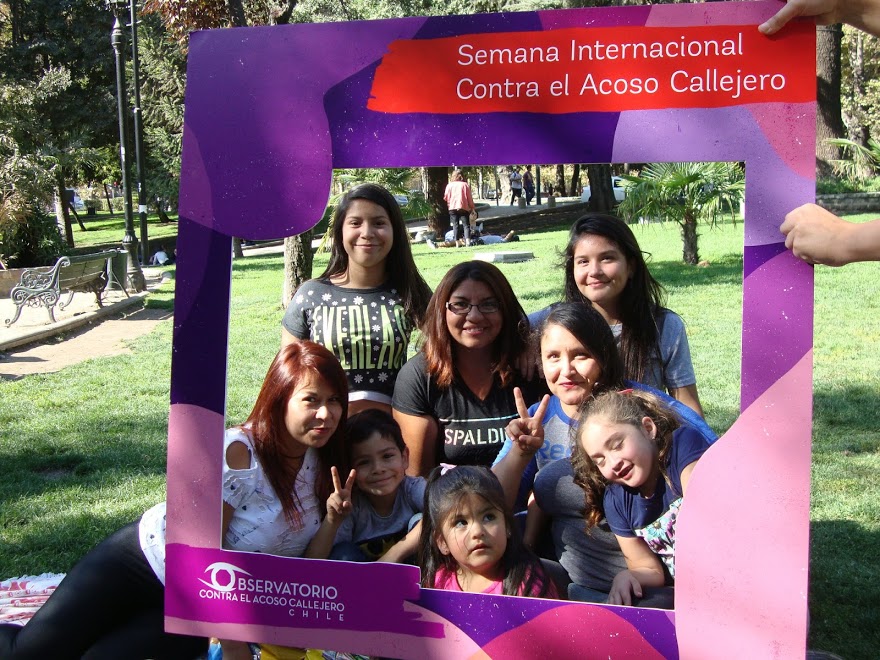

Communicating with others makes it clear that an experience of violence is not an individual experience. When other women say that they have suffered with similar experiences, it changes other victims’ perception of that reality. I think that the most important thing is that they stop thinking that the situation that occurred to them was their fault, and instead, they start to see that there are many other stories like theirs and that it may be part of a larger structure. Their particular case starts to be seen as a collective issue. This is true of all forms of violence, from domestic abuse to street harassment.

But for the last step to be fulfilled, it’s inherently necessary that the public institutions take women’s issues seriously. Women must be listened to in order to change the perceptions of what is “publicly relevant” in policy-makers’ agendas.

Yasmin is a Research Assistant at the Center for Research on Law and Economics at FGV-Rio. She has a Master’s Degree in Social Sciences from PUC-Rio where she wrote her thesis on street harassment and feminists’ struggles for recognition.