Elizabeth Kuster, Brooklyn, NY, USA, SSH Blog Correspondent

When I first started making notes about the harassment I received from random men on a daily basis — and began talking to other women about it, to get their stories — thousands of people around the country were taking buses to Washington so they could march in protest of the Republican president who was trying to limit a woman’s right to choose.

The beating of a Black man by a group of white police officers had created a dark and disturbing negative energy in New York City. Thousands of demonstrators in Times Square were protesting against police departments’ blatant racial discrimination.

A female editor from the same publication that was going to print my first street harassment article was working on an exposé of the pay-or-play casting couch. “Hollywood’s ugliest secret goes public, but will actresses take action against a power broker who can make them a star?” she asked, before quoting a frustrated Halle Berry: “How many complaints will have to be filed before something happens to these guys?”

I can testify firsthand that it is really hard to write about street harassment when there’s so much other terrible shit going on.

Meanwhile, in my personal life, I had just been dumped by the stable (read: unimaginative) older man I thought I loved. (“I need some space,” he said — proving that even when breaking up, he wasn’t capable of originality.) I was in the midst of casually dating an actor/comedian (!) while dealing with crippling menstrual cramps that kept me laser-focused on my uterus for far too many days a month.

And through it all, I was keeping a diary of all of the random ugly comments, stares, propositions and unwanted touches I was receiving from strange men on a daily basis. Let me tell you: It’s hard to “go high” like Michelle Obama when the cultural mood — and the article you’re working on — demand that you focus for months on the lowest of the low. And that lowest of the low is alternately staring at you, ordering you to smile, stroking your hair on the subway train and yelling things like, “I want to f*ck you!” and “You got a fat ass!”

Anyway, I guess it’s time for me to tell you when all of this was going on in my world. You probably think you know. But I bet you don’t.

Hint: It wasn’t 2017.

It wasn’t 2016, either.

Give up?

It was 1992.

1992, people.

Nineteen.

F*cking.

Ninety.

Two.

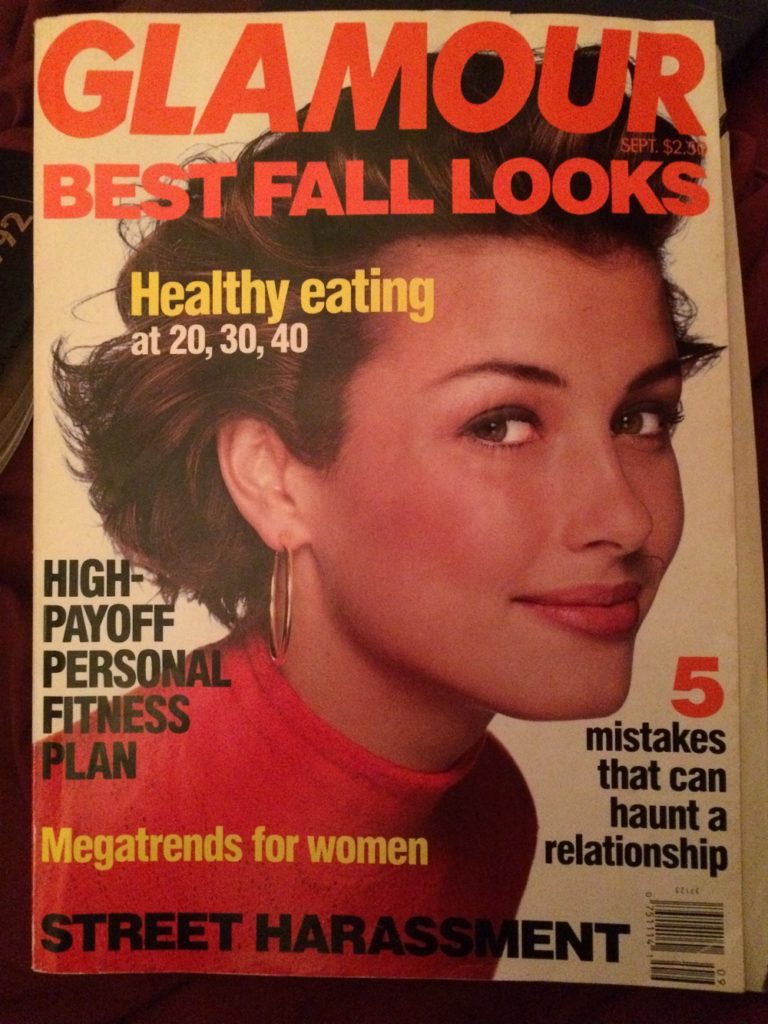

Here’s the cover of the September, 1992, issue of Glamour magazine, which featured my groundbreaking cover story on street harassment:

It was the first time the topic had ever been covered in the mainstream media. A few articles describing a phenomenon called “street harassment” had been published in academic journals or a feminist publication, but that was about it. Back then, I looked toward the future with hope, confident that my article, which ultimately reached 15 million American readers, would empower women and help lawmakers name, fight, and eventually put an end to the problem.

Spoiler alert: It didn’t.

So perhaps my current despair is understandable. Because I seem to be stuck in a feminist’s Groundhog Day. On the face of it, so very little has changed. It’s 25 years since my article came out, and street harassment — and so many other issues — are still huge problems.

The September 1992 issue of Glamour featured Charla Krupp’s prescient article about Hollywood’s casting couch. Today, there’s Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, #TimesUp, and #MeToo.

In May of 1992, there were race riots after the beating of Rodney King. Today, there’s Trayvon Martin, #BlackLivesMatter, the Wall, the Muslim Ban, and ICE.

On April 5, 1992, a massive pro-choice march took place in D.C. Just this week, Republicans tried to shove through yet another misogynist abortion ban. A pussy grabber is in the White House. Women are marching by the millions. And I’m still hoping against hope that I will someday find a human being with a penis who is capable of loving and supporting me and my uterus.

But of course, some things have changed. In my upcoming blogs for Stop Street Harassment, I will revisit my original article and its aftereffects, and explore some of the progress women have made since 1992 in the areas of personal space and physical safety. I’ll celebrate our victories and spotlight areas that still need work. Because those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. And it’s high time for us women to put this particular Groundhog Day to bed once and for all.

Stay tuned.

Elizabeth pitched and wrote the very first mainstream-media article about street harassment. She has held full-time editorial positions at publications such as Glamour, Seventeen and The Huffington Post and is author of the self-help/humor book Exorcising Your Ex. You can follow Elizabeth on Twitter at @bethmonster.