Astrid Nikijuluw, Serpong, Banten, Indonesia SSH Blog Correspondent

English version below.

AREA KHUSUS WANITA PADA TRANSPORTASI UMUM: EFEKTIF?

Kereta pagi meluncur dari stasiun Manggarai menuju stasiun tanah abang. Di dalam penumpang kereta yang berdesak-desakkan, terdapat Agnes yang hendak berangkat menuju kantor. Tiba-tiba dari arah belakang dia merasakan sesuatu yang aneh. Sontak ia segera berbalik badan dan dengan lantang berteriak ke muka pria yang tepat berdiri di belakangnya,”Heh! Kamu sengaja ya gesek-gesek?!” Pria tersebut tidak bisa mengelak dan di stasiun berikutnya dia pun diturunkan oleh petugas dan dilaporkan pada pihak berwenenang.

Kisah diatas merupakan ilustrasi dari kejadian pelecehan seksual yang kerap terjadi di transportasi umum di Indonesia. Banyaknya pengguna kereta di pagi hari mengakibatkan hal-hal seperti ini terkadang sulit dihindari. Kejadian pelecehan seksual seperti yang terjadi pada KRL juga terjadi pada penumpang wanita Bis Trans Jakarta. Beruntung pemerintah cukup peduli dengan hal tersebut. PT Kereta Api Indonesia melalui PT KAI Commuter Jabodetabek (KCJ) terhitung sejak tanggal 1 Oktober 2012 meresmikan kereta khusus wanita. Gerbong khusus ini biasanya terdapat pada gerbong pertama dan gerbong terakhir dari rangkaian KRL. Selain pada transportasi kereta api, transportasi umum lainnya yang juga terdapat area khusus wanita adalah Bis Trans Jakarta. Bis Trans Jakarta juga merupakan sarana umum yang kerap digunakan oleh para pekerja setiap harinya. Dengan adanya area-area khusus wanita tersebut dapat pemerintah Indonesia melalui PT KCJ seperti yang diungkapkan oleh Eva Chairunissa selaku VP Communications PT KCJ dapat mengakomodasi permintaan para pengguna KRL yang merasa risih harus berdempet-dempetan dengan lawan jenis. Selain itu ia juga mengharapkan agar dengan adanya gerbong khusus wanita dapat menghindari kejadian-kejadian yang tidak diharapkan yang korbannya lebih sering perempuan. (https://news.detik.com/berita/d-3504057/sejarah-gerbong-krl-khusus-wanita-di-indonesia-dan-negara-lain)

Saya sebagai salah satu pengguna reguler KRL sangat mengapresiasi tindakan pemerintah dalam mengurangi pelecehan seksual terhadap pengguna wanita baik di kereta maupun di Bis. Kejadian seperti ilustrasi kisah diatas memang sangat mengganggu bahkan cenderung menjadi terror yang cukup menakutkan bagi sebagian wanita terutama para korban dari tindakan asusila tersebut. Saya merasa cukup beruntung tidak pernah mengalami kejadian ini. Dalam pengamatan saya membaca berita-berita, semenjak diadakannya area khusus wanita baik pada kereta api maupun bis trans Jakarta, kasus pelecehan seksual pada transportasi umum tidak sebanyak sebelumnya. Namun apakah hal ini bisa dibilang efektif untuk menanggulangi kasus-kasus pelecehan seksual yang terjadi pada sarana transporasi umum? Saya rasa hal ini masih harus dikaji lebih dalam. Coba sama-sama kita bayangkan. Untuk merasa lebih aman, pengguna kereta wanita yang jumlahnya bisa mencapai puluhan bahkan ratusan ribu per harinya harus rela berdesak-desakkan dalam 2 gerbong yang tersedia. Berita-berita terakhir bahkan menunjukkan kejadian tidak mengenakkan di gerbong wanita seperti adu mulut berebut tempat duduk. Sehingga akhirnya sebagian dari mereka tetap menggunakan gerbong biasa dengan resiko bisa mengalami kejadian pelecehan seksual. Dan apabila memang terjadi, akankah mereka disalahkan karena ‘memilih dengan sengaja’ gerbong yang bukan dikhususkan untuk wanita?

Buat saya kejelasan hukum juga menjadi poin penting dalam rangka pencegahan kasus pelecehan seksual tersebut. Dari penelitian singkat saya mengenai kasus-kasus pelecehan seksual yang terjadi di transportasi umum, pelaku tidak mendapat hukum yang setimpal, bahkan dalam beberapa kasus dibebaskan karena dianggap ‘hanya’ melakukan percobaan. Bukankah segala sesuatu itu berawal dari ‘mencoba’? Kalau berhasil diteruskan. Justru titik krusial menurut saya adalah pada saat mencoba ini. Jika dari hal ini saja sudah ‘dibolehkan’ secara hukum maka jangan heran kalau kasus pelecehan seksual masih akan dan terus berlangsung di transportasi umum. Sejauh ini saya belum menemukan hukuman yang dapat memberikan efek jera kepada para pelaku kejahatan seksual tersebut. Sekali lagi seperti yang pernah saya tulis sebelumnya, hal ini masih belum dianggap serius. Padahal efek yang ditimbulkan kepada para korban sangat dalam. Berdasarkan laman resmi dari Komnas Perempuan (komnasperempuan.go.id) pelecehan seksual dikategorikan ‘hanya’ sebagai perbuatan yang tidak menyenangkan dalam hukum Indonesia. Hal inilah menurut saya yang masih perlu perbaikan.

Upaya pemerintah dengan mengadakan area khusus wanita pada transportasi umum patut kita hargai. Setidaknya pemerintah masih peduli terhadap kasus-kasus pelecehan seksual yang kerap terjadi pada pengguna wanita. Namun alangkah baiknya apabila langkah yang sudah baik ini diikuti pula dengan payung hukum yang sepadan. Kita semua juga tahu tidak mungkin semua penumpang wanita berada di area khusus wanita. Sebagian akan tetap berada di area umum. Dengan hukum yang jelas dan bisa menimbulkan efek jera, akan sangat menunjang usaha pengurangan tingkat pelecehan seksual di area publik dan transportasi umum. Jika tidak maka jangan heran apabila kejadian seperti akan tetap berlangsung tanpa dapat dicegah.

Astrid received her Bachelors of Business at Queensland University of Technology Brisbane Australia. She finished her Master’s Degree at Gadjah Mada University Yogyakarta where she majored in Human Resource Development. Follow her on Twitter at @AstridNiki or on Facebook.

The morning train is on its way from Manggarai station to Tanah Abang station. Among those many people, there was Agnes who is on her way to the office. Suddenly she feels something disturbing. She quickly turns her body angrily and yells at the man standing behind her, “Hei! Are you intentionally touching my back with your p***s?! The man cannot avoid the accusation and in the next station he is brought to the post for further process.

The above story is an illustration of how the sexual harassment happens on public transportation in Indonesia. The crowds of people using the trains and buses in their daily morning makes that behavior seems unavoidable.

Luckily the government has shown their concern towards this matter. Since October 1, 2012, PT Kereta Api Indonesia (Indonesian Train Company) through PT KAI COMMUTER JABODETABEK (KCJ) has run women-only transit carriages in the front and back of the train. In addition to the train, the trans-Jakarta bus, which is also a common mode of transportation, has a special area for women, the first few rows behind the driver.

Eva Chairunissa, the VP Communications of PT KCJ, said the women-only areas are meant to help women riders feel more comfortable. The government hopes that the women-only areas are decreasing the levels of sexual harassment and that people are more comfortable using the public transportation.

I, as one of the public transportation user, really appreciate what the government has done in order to reduce the level of sexual harassment in public transportation. I am lucky enough to never have experienced such an incident, but based on what I’ve read in the news, the sexual harassment cases have gone down since the launch of the women-only areas.

However is it really effective at decreasing the level of sexual harassment in public transportation? I think it still needs to be reviewed. Let’s imagine. To feel more comfortable and safe, women passengers, who are up to hundreds of thousands in number each day have to use only two carriages on the train or the first few rows on the trans-Jakarta bus. There is simply not enough space for all women and there are often arguments over seating. Thus, many women still use the regular area in the public transportation and face the risk of experiencing sexual harassment there. And of course if and when that happens, some may blame them for choosing the “wrong” area.

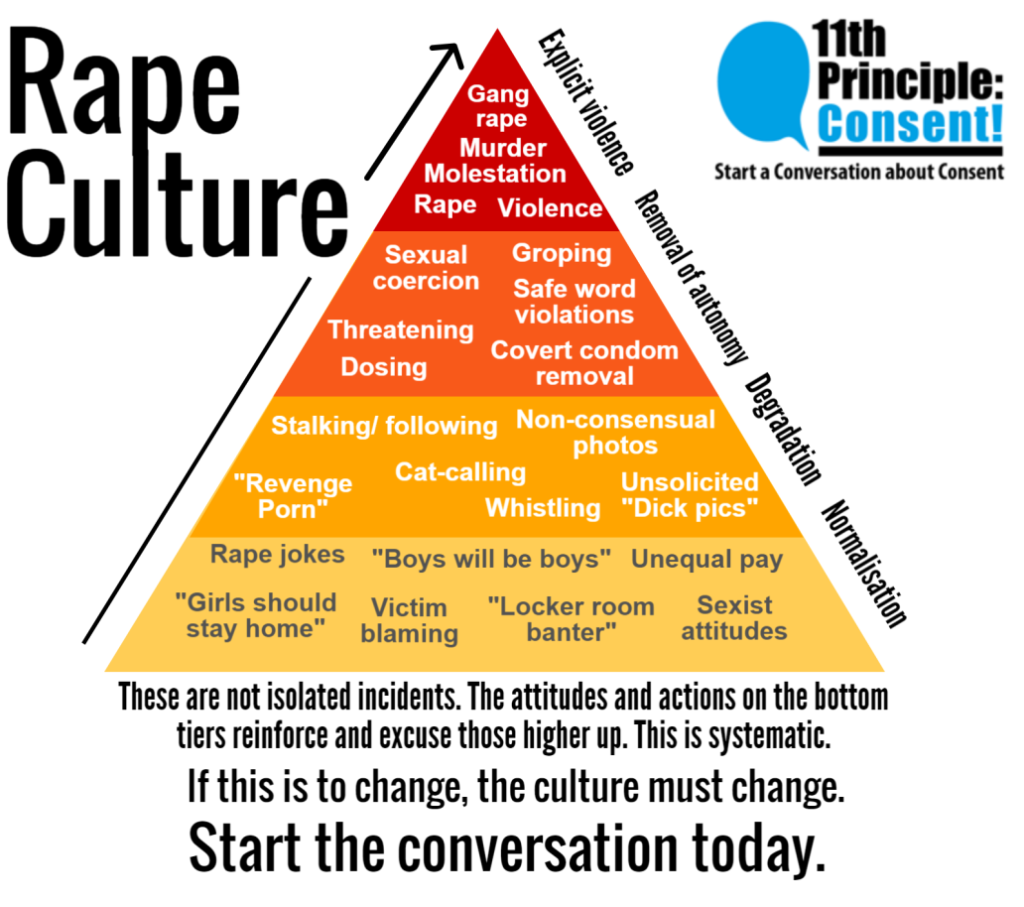

In my opinion, women-only options are not enough. The clarity of the law is also very important in order to prevent sexual harassment. From my own research of news stories, the punishment for the perpetrators are not worth it, even in some cases they are not being punished because they were ‘only’ just ‘trying’ to sexually harass the victim…. But doesn’t everything start from trying? If they succeed, they may do it again. The crucial moment for me is at the stage of ‘trying’. If this stage is ‘allowed’ according to law, then no wonder sexual harassment cases in public transportation still occur. Thus far, I haven’t found any punishment that would realistically act as a deterrent to the perpetrators. Once again, as my two last articles had stated, this kind of behavior has not yet been taken seriously.

Based on the KOMNAS PEREMPUAN (National Commission On Violence Against Women) website, by law, sexual harassment is categorized only as a “disturbing behavior” that is on the same level as other behavior, such as cheating. This is what needs to be improved. The current sexual harassment law is not at all adequate to accommodate the range of every day behaviors.

The government’s plan for preventing sexual harassment in public transportation by creating women-only areas is well-respected. At least the government has done something. However, it would be much better if this action was accompanied with a decent law, especially as many women still use the regular sections of public transportation. Therefore a stronger law will help reduce the sexual harassment cases on a larger scale in public spaces, including public transportation. Otherwise, we can’t be surprised when sexual harassment incidents continue to occur.

I like to walk and when the warmer weather hits, I go for walks as part of my self-care routine. I also walk to work and during work. As a domestic violence and sexual assault advocate, I sometimes have to respond to calls at our local services center or hospitals so I usually walk to these places to avoid wasting time looking for parking.

I like to walk and when the warmer weather hits, I go for walks as part of my self-care routine. I also walk to work and during work. As a domestic violence and sexual assault advocate, I sometimes have to respond to calls at our local services center or hospitals so I usually walk to these places to avoid wasting time looking for parking.

In philosophy, the concept of “disrespect” describes situations of injustices that marginalized groups and minorities suffer in a society. In my thesis “My name isn’t pssst!”: Street harassment and feminisms’ struggle towards legal recognition”

In philosophy, the concept of “disrespect” describes situations of injustices that marginalized groups and minorities suffer in a society. In my thesis “My name isn’t pssst!”: Street harassment and feminisms’ struggle towards legal recognition”