This is a guest blog post for International Anti-Street Harassment Week 2013 by Lea Goelnitz, Germany.

Street harassment is a strategy to scare women away from the public space so they do not work or go to school, earn their own money, go into politics, make decisions, claim property and take power.

I feel harassed when I receive unwanted attention in the street (for the record, basically all of it is unwanted), and the only one who decides what is unwanted is myself. When I am alone in public, I am usually going somewhere deliberately. So when strange men talk to me or stare at me, that means it is assumed that whatever I am up to do is less important than what they are doing and it is fine to interrupt me and demand my attention.

I feel harassed when I receive unwanted attention in the street (for the record, basically all of it is unwanted), and the only one who decides what is unwanted is myself. When I am alone in public, I am usually going somewhere deliberately. So when strange men talk to me or stare at me, that means it is assumed that whatever I am up to do is less important than what they are doing and it is fine to interrupt me and demand my attention.

Even if that does not physically hurt me, it destroys my feeling of security and shows me that my time and me as a person is perceived as less valuable compared to others. So the message to me on a personal level is that I am made to feel uncomfortable and out of place because I dared to be in the male dominated public space, where according to them I should not be. I am being punished for participating in everyday life.

If I ask male friends what precaution they take when they step out into the street, they are confused. They do not take another way, dress differently, behave differently, try not to be too drunk and go home earlier or take a taxi instead of walking. They do not do any of these things, meaning that they feel safe enough just doing what they want.

The permanent feeling of insecurity makes women follow unwritten rules to go out in public.

They are always careful, they are made to think about what to wear (although not at all relevant as a strategy to avoid harassment), avoid going out alone, go in groups or with trustworthy male friend, avoid being out in the dark, avoid certain routes, avoid to generate attention, change their body language and attitude.

We debate on the advantages and disadvantages of pepper spray and other “weapons”, we strategize on routes to take to places and on responses we give in which situation to which men, considering what is possible to do and say in regard to the amount of men, the level of aggression and if it is daytime or night time. We applaud each other when we managed to react in a way, which did not leave us feel powerless.

For all these efforts we are neither rewarded by feeling safe, nor are these restrains publicly acknowledged.

The women-focused victim-blaming approach did NOT result in a decrease of harassment, rape, murder and other gender-based violence. More women might report more crimes. But clearly they do not feel safer.

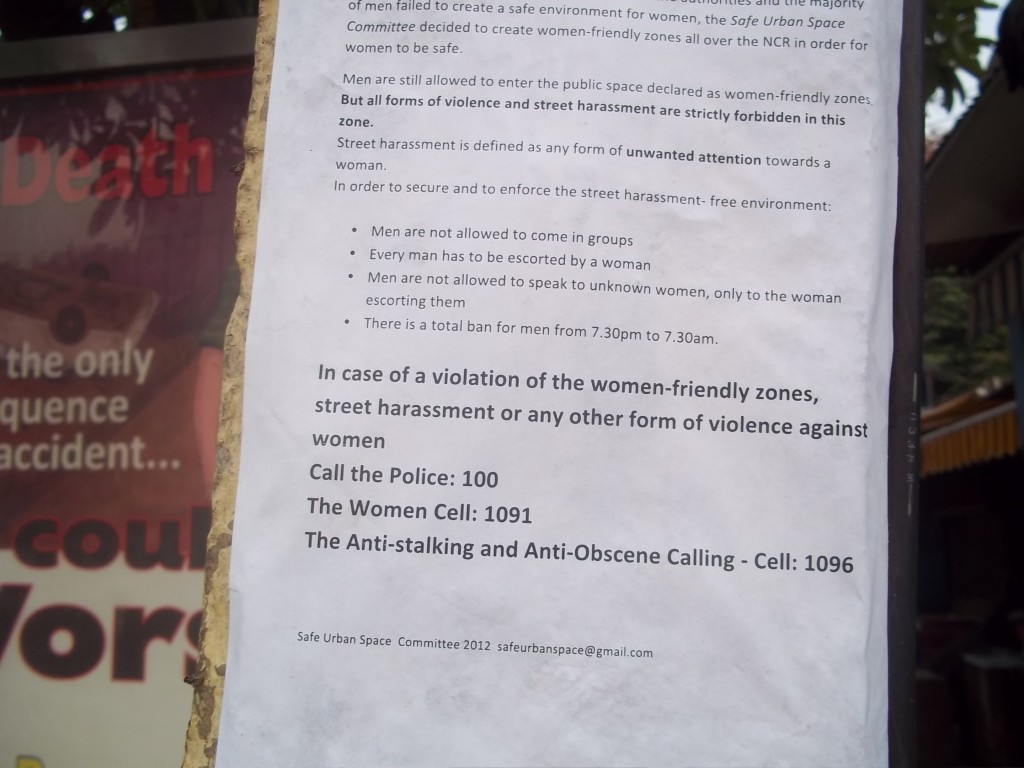

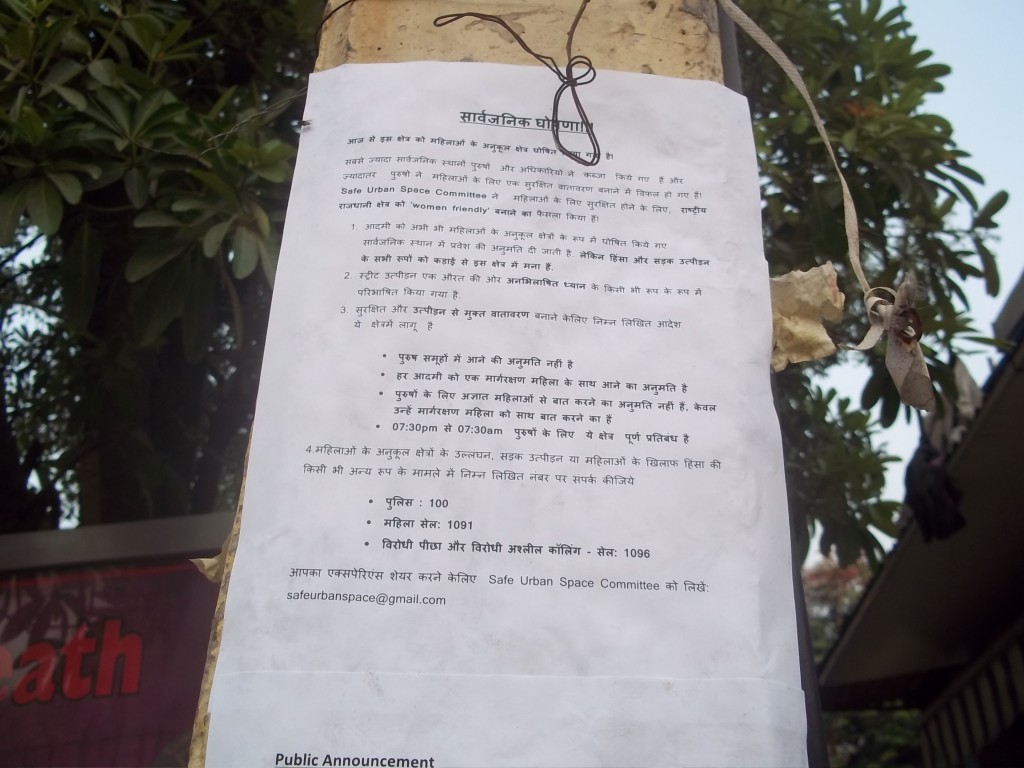

The women-only compartment in the Delhi metro inspired the Safe Urban Space Initiative I started with a friend in a Delhi neighborhood. Obviously, a women-only zone is backwards and no long-term solution. So the plan was to create women-friendly zones instead of women-only zones, in which men could enter, but in order to secure and to enforce a street harassment-free environment, these (half-seriously meant) opposite rules of what women follow in order to be safe, applied;

The women-only compartment in the Delhi metro inspired the Safe Urban Space Initiative I started with a friend in a Delhi neighborhood. Obviously, a women-only zone is backwards and no long-term solution. So the plan was to create women-friendly zones instead of women-only zones, in which men could enter, but in order to secure and to enforce a street harassment-free environment, these (half-seriously meant) opposite rules of what women follow in order to be safe, applied;

1. Men are not allowed to come in groups

2. Men have to be escorted by a woman, so that other women can see that he is ok.

3. Men are not allowed to approach and speak with unknown, in case there is need for communication, this can happen via the women who escorts him.

4. No cameras, no mobile phones, so that men cannot take pictures of women.

5. No staring! If men are unsure if they are still creating an atmosphere of harassment, they have the option to be blindfolded

6. There is a total ban for men to be outside from 7.30 p.m. to 7.30 a.m.

The approach is perpetrator-based and solely focuses on what men need to do/ need to stop doing in order for women to feel safe.

Back in Germany, I got increasingly annoyed with the media coverage of gender-based violence outside of Europe. It is easier to talk about a (far away) country and portray that as barbaric and then not address the same issues at home, but instead using the same victim-blaming arguments.

This actually inspired a new initiative “There is no dress code for street harassment,” an online- exhibition of clothing.

In order to shut down the re-occurring argument of blaming women for the way they dress, “provoking” men, the aim of the campaign is to visually demonstrate the range of clothing women are wearing when harassed.

Lea became an anti-street harassment activist when living in Delhi. Now living in Berlin, she is also involved in some anti- street harassment action.