Yasmin Curzi, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, SSH Blog Correspondent

For months, feminist Facebook pages announced and spread the word: A women’s strike was going to happen in Rio on Thursday, March 8, 2018.

The page “8M – RJ”, one of the most vital representatives of the strike, says in a manifesto on their Facebook page that they “belong to national and international feminist movements” and are also from “labor’s unions, parties, collectives and other social movements.”

They are also from Black women, lesbian and trans* movements. The heritage of the Russian Revolution is also highlighted. “We are the vanguard in revolutionary processes in Brazil and worldwide. And the March 8th of 1917 remarks it when, in a context of crisis and with country’s brutality, women factory workers organized a strike which was the very first cause of Russian Revolution.”

It was expected nearly 30 thousand women would attend the rallies and march in the city center.

I woke up on March 8 to the news that women from Landless Movement had occupied a Globo[1] graphic park in Rio in defense of democracy[2]. It gave me hope that even the torrential rain that day wasn’t going to stop women from their combative and fiery demonstration. This article is about what I saw there.

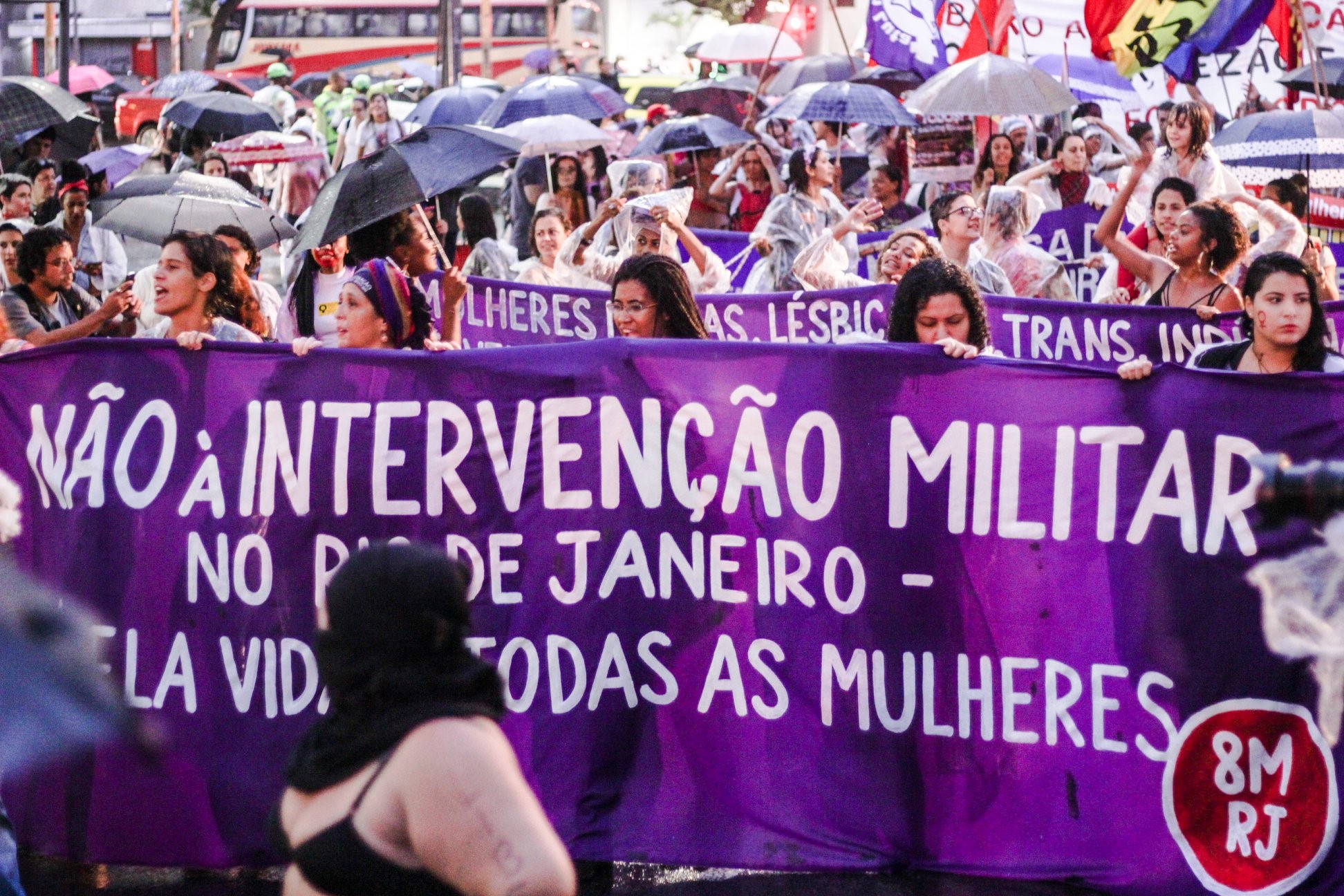

As soon as I arrived, because of the rain, I spotted the tent for the women’s sector of Labor’s Party. They were distributing material to inform the people of the risks of the “evil’s pack” from President Michel Temer’s administration. A sound car was parked in the square in front of Candelaria’s Church, and women with legislative mandates were speaking against Temer’s administration. In their speeches they were opposing the federal intervention in public security in Rio de Janeiro[3], against the conservative mayor of Rio de Janeiro Crivella and gender-based violence, and speaking in favor of women’s reproductive rights, legal abortion and political representation.

As soon as I arrived, because of the rain, I spotted the tent for the women’s sector of Labor’s Party. They were distributing material to inform the people of the risks of the “evil’s pack” from President Michel Temer’s administration. A sound car was parked in the square in front of Candelaria’s Church, and women with legislative mandates were speaking against Temer’s administration. In their speeches they were opposing the federal intervention in public security in Rio de Janeiro[3], against the conservative mayor of Rio de Janeiro Crivella and gender-based violence, and speaking in favor of women’s reproductive rights, legal abortion and political representation.

At 6 p.m., the march began. It was time for “Slam das Mina”[4] to make a splendorous presentation in the sound car. Women’s World March Brazil had a drum music group who were chanting and shouting lyrics like, “Women against war, women against the capital! / Women for the end of racism and neoliberal capitalism! / Women want the land, women want to be equal! / Women want international socialism and feminism.”[5]

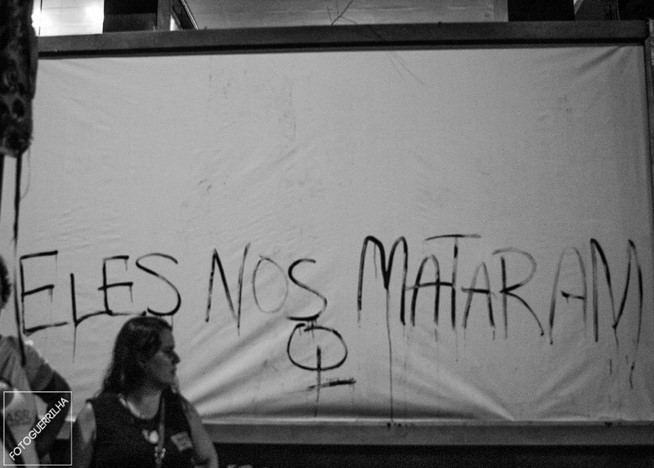

We marched until 8 p.m. and we finished with a big circle of women holding hands and chanting in solidarity with Latin America and each other. We spoke against feminicide and male privileged citizenship and in favor of a real democracy – one truly produced by the people.

Former president Dilma Vana Rousseff’s impeachment opened a wound in Brazil’s already fragile democracy – for it has always been with its economy under the control of international market’s actors. Neoliberal measures of Temer’s administration, in relation to labor laws, social security, art, culture and public security, do not seem to come from the popular will. All of the public policies against poverty of the Labor’s Party governments have suffered somehow with the austerity actions. Likewise, institutions created by Labor Party toward the combat of racism and gender inequality were affected, e.g. Special Secretariat of Policies for Women[6] lost its statute of Ministry to become a part of Justice Ministry, in a dismantling process.

For the political scientist Flavia Biroli[7], “parliamentary coup of 2016 put an end to the channels of dialogue between government and feminist movements”. In this way, the advances conquered by social movements struggles since the end of military dictatorship have been under constant menace. Neoliberal capitalism, holding hands with conservatism, push its agenda against gender equality with fake news and spreading fear to canalize people insecurities in relation to social changes — i.e. transformations in sexuality and in family models — in order to turn society against left parties and social movements. To explain better, this economic agenda isn’t in public debate, but hidden inside a moral agenda.

Biroli also points to Patricia Collins’ work about citizenship, saying that the sub inclusion of all women and all Black people signifies the super inclusion of white men – which are a numeric minority in Brazilian society. The struggle against power and wealth concentration should be the fundamental concern of feminist movements in order to redefine the concept of democracy.

The usual concept of democracy, centered in representative institutions, neglect discussions of relevant subjects which have huge impacts on minorities everyday lives. We can say that the “institutions of public life”, in reality, were built by the interests and discussions of the power elite. And if the distance of Brazilian parliament from the actual people is extensive, and we are living in a context where social movements can no longer act with and alongside the State, it’s terribly necessary to engender an other type of democracy that could be able to really articulate the popular will. True channels of civil society to achieve the representative institutions, such as mechanisms to enable the pressure from civil society over parliamentarians, and also for people to decide the destination of public resources.

Fundamentally, from my experience as a militant, feminist movements have been the ultimate source of hope against apathy. They have the potential to combat the hegemony of neoliberal and conservative sectors, for they incarnate the project of an inclusive democracy. And, even with the constant backlashes, young girls and women are more and more conscious that they have to fight for their rights – that they aren’t fully conquered, for liberal democracy is controlled by men and our rights are always seen as a bargaining chip in legislative trading desks. We have a lot to achieve and the organization is just beginning.

[1] The country’s largest TV and radio broadcasting company that supported the military dictatorship, indirectly supported Dilma’s impeachment and helps in Lula’s persecution, and has an explicit neoliberal agenda against left sectors, despite being a government grantee and despite the fact that the guarantee of the right to communication should be a State duty.

[2] See: http://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/cidadania/2018/03/mulheres-ocupam-parque-grafico-da-globo-no-rio

[3] A populist way of Temer’s to conquer some kind of legitimacy was by putting the National Army in the command of public security in Rio de Janeiro. Also, now there are two militaries occupying chairs as ministries. See: http://www.rioonwatch.org/?p=42012

[4] A slam poetry group of pheripheral women that make poetry with their everyday experiences and about the impacts of State and male violence in their individual trajectories.

[5] In the original “Mulheres contra a guerra, mulheres contra o capital! Mulheres contra o racismo e o capitalismo neoliberal! Mulheres querem a terra, mulheres querem ser igual/ Mulheres querem feminismo e socialismo internacional.”

[6] See Lourdes Bandeira, “Que vont devenir les actions du Secrétariat de Politique pour Femmes (SPM) au Brésil?” Available at: <https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-du-genre-2016-3-page-243.htm>

[7] See Flavia Biroli “Gênero e desigualdades: os limites da democracia no Brasil” 1ª Ed. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2018.

Yasmin is a Research Assistant at the Center for Research on Law and Economics at FGV-Rio. She has a Master’s Degree in Social Sciences from PUC-Rio where she wrote her thesis on street harassment and feminists’ struggles for recognition.