I’m so excited that our Safe Public Spaces Champion awardee Muriel Bowser is MAYOR of Washington, DC!

I’m so excited that our Safe Public Spaces Champion awardee Muriel Bowser is MAYOR of Washington, DC!

“”It’s my charge to make [D.C.] greener, healthier, safer and more fiscally stable than we find it today,” she said.

Formerly D.C.’s Ward 4 councilmember, Bowser is now just the second woman to lead the District. Early in her inaugural remarks, she thanked the female mayors of other major cities, saying, “Today, because of you, I am one too.”

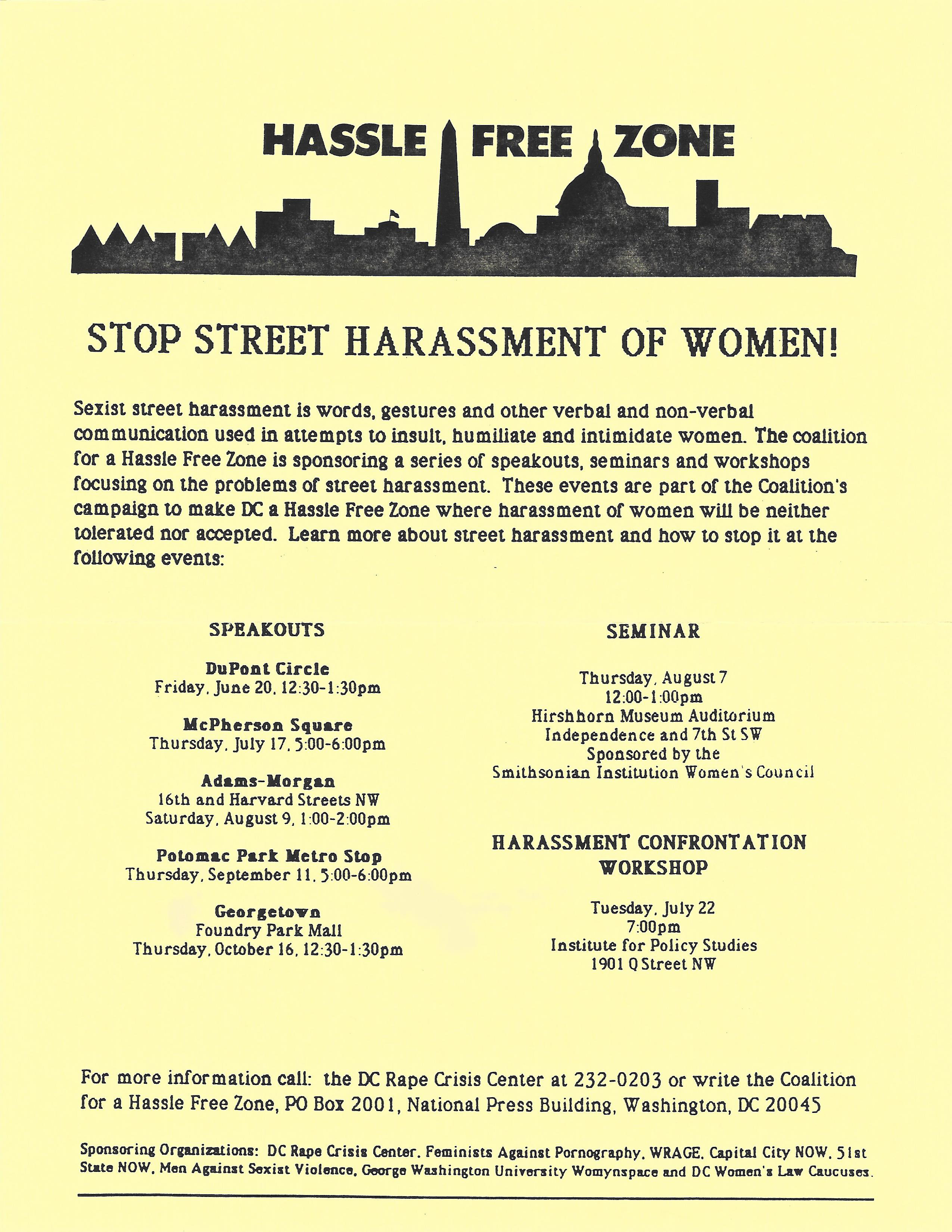

It’s in large part thanks to her that the Washington Metropolitan Area has an anti-harassment transit campaign. In 2012 when I was part of a group organized by Collective Action for Safe Spaces (I was one of their board members at the time) that testified about harassment before the DC city council and the all male WMATA leadership responded by saying harassment wasn’t a problem, Bowser told them “as a woman I feel differently” and told them to do something. And they did. #WomenLeaders