Anti-street harassment campaigns can serve many purposes. They can raise public awareness that street harassment is a problem and educate people about why it occurs. They also can lead to concrete changes, like anti-harassment public service announcements on the subway and street lamps on a busy but darkened road.

Here are four case studies of anti-street harassment campaigns in Chicago, New York City, Mauritius, and Cairo.

A list of other campaigns, followed by tips and ideas for carrying out one’s own campaign conclude the section.

Since 2003, members of the Rogers Park Young Women’s Action Team (YWAT) have been leading an anti-street harassment campaign in Chicago, Illinois. To start, the eight founding YWAT members surveyed 168 neighborhood girls, ages 13 to 19, about street harassment and interviewed 34 more in focus groups. They published their findings in a report titled “Hey Cutie, Can I Get Your Digits?” The results were astounding: 86 percent had been catcalled on the street and 60 percent said they felt unsafe walking in their neighborhoods.

Since 2003, members of the Rogers Park Young Women’s Action Team (YWAT) have been leading an anti-street harassment campaign in Chicago, Illinois. To start, the eight founding YWAT members surveyed 168 neighborhood girls, ages 13 to 19, about street harassment and interviewed 34 more in focus groups. They published their findings in a report titled “Hey Cutie, Can I Get Your Digits?” The results were astounding: 86 percent had been catcalled on the street and 60 percent said they felt unsafe walking in their neighborhoods.

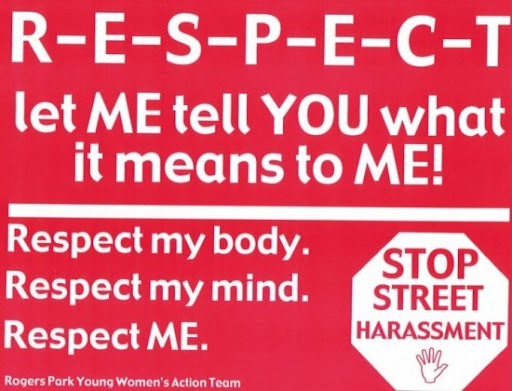

With their report in hand, the young women began a successful and well-organized anti-street harassment campaign. For example, they worked with local business owners to let them know men standing outside their stores harassed them and made them feel unsafe. Over 120 business owners agreed to post signs in their windows that said, “R-E-S-P-E-C-T let me tell YOU what it means to ME! Respect my body. Respect my mind. Respect ME. STOP STREET HARASSMENT.” The efforts of YWAT led to fewer men loitering outside businesses, harassing girls and women.

YWAT also held public forums on street harassment and worked with local leaders, including police and elected officials, to address public safety. One of the YWAT’s major victories was the installation of more street lights along Howard Street and Morse Avenue. City officials also installed a camera on Morse Avenue to better monitor street activities.

In May 2006 and May 2007, YWAT organized a Citywide Day of Action against Street Harassment Campaign to convey the message “the streets belong to ALL OF US.” People participated in 140 forms of activism that day. The young women also hold anti-street harassment workshops at high schools, conferences, and community events. Their latest initiative is working to make public transportation safer in Chicago.

In May 2006 and May 2007, YWAT organized a Citywide Day of Action against Street Harassment Campaign to convey the message “the streets belong to ALL OF US.” People participated in 140 forms of activism that day. The young women also hold anti-street harassment workshops at high schools, conferences, and community events. Their latest initiative is working to make public transportation safer in Chicago.

During the spring of 2009, the group of teenage and college-age women surveyed 639 Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) riders, mostly young women. They found that sexual harassment is common on CTA buses and trains. Over half of the survey respondents said they had been sexually harassed and 13 percent said they had been sexually assaulted. Forty-four percent of those surveyed said they had witnessed harassment or assault.

Armed with their survey results, YWAT met with the CTA Board and other key decision makers and asked that CTA employees receive training on how to deal with harassment and that CTA post more information about how people can report harassers. In a major victory for YWAT, only one month later in July 2009, the CTA announced it would expand its policies on how bus and rail operators deal with harassers. The CTA said it would update its public safety tips brochures to include information about harassment and how to report it.

In November 2009, the CTA began to made good on their word and launched PSAs about harassment. Their new print PSA states, “If it’s unwanted, it’s harassment. Touching. Rude comments. Leering. Speak up. If you see something, say something.” At the bottom of the poster there is information for whom to contact if a rider is the target of sexual harassment.

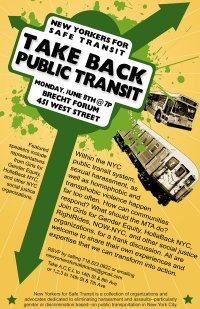

Since 2007, RightRides for Women’s Safety, Hollaback, Girls for Gender Equity, and other groups have been working to make public transportation safer. In 2009 they formed the group New Yorkers for Safe Transit (NYFST).

In 2007, they helped with a survey on sexual harassment and assault on the subway, conducted by the Office of the Manhattan Borough President Scott M. Stringer. Of the 1,790 people who responded to the online survey (the majority of whom were women), 63 percent said they had been harassed and one-tenth had been sexual assaulted on the subway system. Only four percent of people who were harassed reported it, as did only 14 percent of those who were assaulted. Forty-four percent said they had witnessed sexual harassment.

One of the report recommendations was a Public Service Announcement (PSA) campaign about sexual harassment on the subway. The next year, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) printed ads but shied away from posting them, claiming they were afraid they would encourage sexual harassment. Through a number of grassroots tactics, including an op-ed in the New York Daily News by HollaBack co-founders Emily May and Sam Carter, combined with a joint collaboration between RightRides, the offices of Council Member Peter Vallone and Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, the NYFST coalition issued letters calling for the release of the campaign with the ultimatum of a holding press conference on the topic. The MTA caved and posted the ads; a significant victory for the activists.

In August 2008, MTA posted the PSA in 300 subway cars with 2,000 posters. It reads “Sexual Harassment is a Crime in the subway, too – A crowded train is no excuse for an improper touch. Don’t stand for it or feel ashamed, or be afraid to speak up. Report it to an MTA employee or police officer.” In February 2009, the MTA launched an audio version of the PSA for the newest subway cars.

After continuing to work together to put pressure on the M TA to better address the problem of sexual harassment and assault on the subway system, in March 2009, the groups officially formed NYFST. They began a series of community dialogue projects with various nonprofit agencies serving women, youth, elders, LGBTQ and LGBTQ persons of color communities, and low-come individuals to better capture quantitative and qualitative data of harassment and violence in mass transit. They also began working to secure funding to conduct a scientific survey of 5,000 people to capture the mass transit harassment and assault numbers not being recorded. They met with various legislators about the need for policies that would require public transportation crime data transparency. With their support, in November 2009, Councilwoman Jessica S. Lappin, a Manhattan Democrat, introduced a bill that would require the police to collect data on sexual harassment in the subways.

TA to better address the problem of sexual harassment and assault on the subway system, in March 2009, the groups officially formed NYFST. They began a series of community dialogue projects with various nonprofit agencies serving women, youth, elders, LGBTQ and LGBTQ persons of color communities, and low-come individuals to better capture quantitative and qualitative data of harassment and violence in mass transit. They also began working to secure funding to conduct a scientific survey of 5,000 people to capture the mass transit harassment and assault numbers not being recorded. They met with various legislators about the need for policies that would require public transportation crime data transparency. With their support, in November 2009, Councilwoman Jessica S. Lappin, a Manhattan Democrat, introduced a bill that would require the police to collect data on sexual harassment in the subways.

Currently, NYFST are working on fundraising and collecting mass transit stories online and through focus groups. They also had made progress on several other initiatives.

In December 2009, their continued efforts and pressure led to more change in the public transit system. MTA reports they will increase the number of automated messages in the subway stations warning against assaults and they will begin distributing anti-groping posters and brochures. MTA will meet with NYFST in early 2010 to create a more comprehensive anti-harassment PSA that takes the onus off the survivor, provides a hotline number, bystander information, and details about how perpetrators will be held accountable for their actions. Building off the method Holla Back NYC uses for “hollaback”ing at harassers with camera phone photos, NYPD is working on a pilot program that would enable victims to send photos of harassers to police officers, who can investigate the case even after the harasser has slipped away into a crowd.

Street harassment is common in Mauritius, an island off the coast of southern Africa. Alyssa Fine, a Midwest native went to Mauritius as a Fulbright scholar to conduct research on sexual harassment in the workplace. During her data collection and analysis, it became clear that many women also wanted to talk about public harassment.

Street harassment is common in Mauritius, an island off the coast of southern Africa. Alyssa Fine, a Midwest native went to Mauritius as a Fulbright scholar to conduct research on sexual harassment in the workplace. During her data collection and analysis, it became clear that many women also wanted to talk about public harassment.

Because of the anecdotes she heard, Fine decided to research and write a report on street harassment in Mauritius; it was the first of its kind, sponsored by Soroptimist International Ipsae Mauritius. A companion 2009 anti-street harassment campaign called Respekte Nu (Creole for Respect Us) became part of a six-year, worldwide Amnesty International campaign of Stop Violence Against Women (SVAW). With the help of colleagues, Fine designed the campaign and oversees its implementation.

The campaign launched with a press conference attended by representatives from non-governmental, private and governmental agencies. Fine and her colleagues shared the results of their study and details of the campaign and ended with a participatory activity in which attendees could write down their ideas about how best to address street harassment.

The anti-street harassment campaign was multi-dimensional. Some activities included a Fam a Fam — or Woman to Woman — forum where 45 women and girls had a safe space to talk about street harassment. There was a youth art contest for which 30 young people submitted essays/poems and drawings/photographs on street harassment. One of their most successful campaign initiatives has been speaking on radio shows. They also held a man to man platform with trainings, youth education, brochure distributions, and street theater.

Because of the sharp increase in the number of women sharing their experiences with public harassment and a lack of societal awareness of the problem, in 2005 the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights (ECWR) launched an anti-sexual harassment campaign called “Making Our Street Safer for Everyone.” Volunteers are the driving force of ECWR’s campaign. They meet monthly to discuss ideas and plan initiatives.

Because of the sharp increase in the number of women sharing their experiences with public harassment and a lack of societal awareness of the problem, in 2005 the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights (ECWR) launched an anti-sexual harassment campaign called “Making Our Street Safer for Everyone.” Volunteers are the driving force of ECWR’s campaign. They meet monthly to discuss ideas and plan initiatives.

Initially, ECWR conducted informal, voluntary surveys of over 2,000 people. An overwhelming number of female respondents said sexual harassment was part of their daily life. Eighty-three percent of women said men had sexually harassed them and 62 percent of men admitted to perpetrating sexual harassment. Fewer than two percent of women reported going to the police for help. ECWR published their results in a 2008 report “Clouds in Egypt’s Sky, Sexual Harassment: from Verbal Harassment to Rape.” The report garnered lots of attention in Egypt and around the world.

Next, ECWR organized several forms of public awareness, including:

1. Distributing flyers with information like definitions of harassment, existing laws, how to file a police report, and how to campaign on the issue.

2. Creating public service radio announcements about sexual harassment.

3. Staging an anti-sexual harassment demonstration with 250 women and men on the steps of the Press Syndicate.

4. Holding press conferences and public awareness days at cultural centers, institutions, and hotels. Events have featured presentations and discussions on Egypt’s sexual harassment laws, women’s image in the media, the sociological and psychological impacts of harassment, group discussions on how to address the problem, self defense workshops, and live music and relevant films.

On the advocacy front, ECWR has worked with legal volunteers to draft a new sexual harassment law that increases jail time and fines for violation and puts more pressure on police to stop incidents and take the concerns of targets seriously. ECWR worked with allies in parliament to have this legislation introduced. They also have been working on holding roundtable discussions with ministry of interior representatives.

On the advocacy front, ECWR has worked with legal volunteers to draft a new sexual harassment law that increases jail time and fines for violation and puts more pressure on police to stop incidents and take the concerns of targets seriously. ECWR worked with allies in parliament to have this legislation introduced. They also have been working on holding roundtable discussions with ministry of interior representatives.

ECWR has been reaching out to youth, too, by training teachers and social workers to sensitize them to the issues of public sexual harassment and helping them know how to discuss the issues with their students. They recently released an animated five minute educational film and workbook for teachers to further help facilitate school discussions, including through painting and coloring. The resources teach children to trust others but to be careful and aware of inappropriate behavior and to learn the difference between appropriate and inappropriate language.

Related, activists who used to work with the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights launched HarassMap, a system for reporting incidences of sexual harassment via SMS messaging and online forms. The tool gives women a way to anonymously report incidences as soon as they happen. By mapping these reports online, the entire system acts as an advocacy, prevention, and response tool, highlighting the severity and pervasiveness of the problem.

- Blank Noise (India)

- Fighting Street Harassment of Women in Yemen (Yemen)

- Girls for Gender Equity (NYC)

- Helping Our Teen Girls In Real Life Situations, Inc.: “Anti-Street Harassment Campaign” (Atlanta)

- Hollaback

- LASH Campaign (London Anti-Street Harassment Campaign)

- ObjecDEFY (Jordan)

- One Step Too Far (Wales)

- Real Men Don’t Holla (NYC)

- Safe Cities Project (United Nations)

- Safe Delhi Campaign (India)

- Street Harassment Project (NYC)

- UNICEF’s efforts to end eve teasing (Bangladesh)

A Few Tips for Campaigning and Lobbying:

If you want to start or participate in an anti-street harassment campaign (large or small), here are some ideas and tips to help you. Also note that you do not need to be a professional to get started or to organize; campaigns often are run by regular people volunteering their time and expertise.

1. Form a coalition of concerned persons and/or organizations to work on the issue. If possible, include individuals who can offer a variety of viewpoints and experiences, including teenagers and young women, women of color, members of the LGBQTI community, women with disabilities, sex workers, low-income women, and homeless women.

2. Decide on preliminary goals for the campaign and create a plan for collecting data about women’s experiences.

3. Find out the experiences of women in your community by surveying them, interviewing them, and/or holding focus groups. Draft a report with the findings.

4. With the report findings, decide, as a group, what changes need to be made and what initiatives to work on.

5. Divide up the task work among groups, and plan to have regular meetings to share progress, ideas, and help each other with any challenges.

6. Create goals for specific timeframes, such as, in one month we will do X, and in six months we will have done Y, and in one year, we will have achieved Z.

7. Work on the goals, issue press releases to inform the public about your intentions and progress. Include ways for members of the public to become involved in the initiatives (from attending events to lobbying their local congress person to posting anti-street harassment signs in their neighborhoods).

The following are some ideas for campaign member activities:

1. Take the report to local council people who are sensitive to women’s issues and discuss street harassment with them. Propose a law that fines men who verbally harass women in a sexual or sexist manner. Ask them to introduce it and support it.

2. Meet with the local police departments about street harassment. If they do not already, ask that police officers receive sensitivity training regarding street harassment. Also, when surveying women about their harassment experiences you can ask them where they are harassed and create a map tracking this data. If there are problem areas, show the data to the police officers and ask them to have officers patrol the area.

3. Talk to local businesses that have employees who work outside about the general problem of street harassment. Ask them to be proactive and to publish a phone number on their work vehicles and/or on a sign at a worksite that people can call if the employees harass women. Ask them to post signs saying “This is a harassment-free zone.”

4. Ask the city council to hold a hearing on street harassment and/or conduct a city-wide study on the issue to better understand its prevalence and what can be done to stop it.