~ en español ~

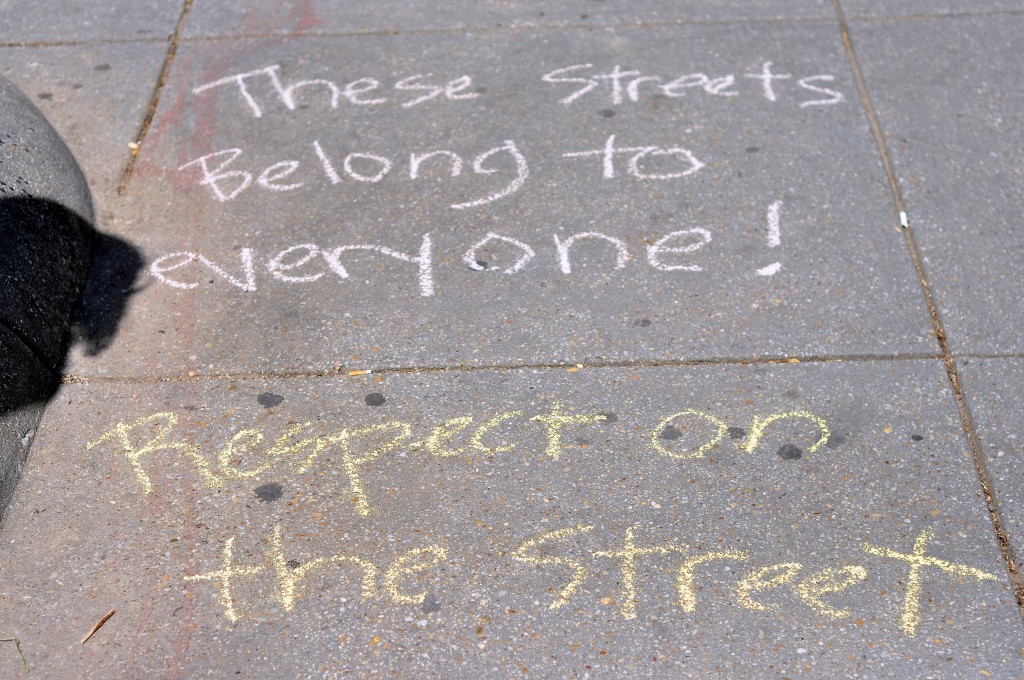

Gender-based street harassment limits people’s access to public spaces and lowers their comfort level there. It can cause people to “choose” less convenient routes and alter their routines; give up hobbies and change habits; and even quit jobs or move neighborhoods or simply stay home because they can’t face the thought of one more day of harassment. This page addresses street harassment all female-identified individuals face, then harassment members of the LGBQTI community experience.

All Women/Female-Identified Individuals:

Unlike the harassment based on other factors (e.g. racial harassment, homophobic harassment, disability harassment), the street harassment of girls/women because of their gender is usually not taken seriously and few other groups address it. It’s seen as a joke, compliment, or their fault. It is none of these things.

Unlike the harassment based on other factors (e.g. racial harassment, homophobic harassment, disability harassment), the street harassment of girls/women because of their gender is usually not taken seriously and few other groups address it. It’s seen as a joke, compliment, or their fault. It is none of these things.

Impedes Equality

In reality, street harassment limits women’s peace of mind and mobility, making it a gender equality and human rights issue. No country has achieved gender equality and no country ever will until street harassment ends. Additionally, for most women, street harassment begins around puberty and being the recipient of it signifies to many of them the transition from girlhood to womanhood. That is a sad, sad statement about how girls/women are treated – and expect to be treated – in our society.

In 2013, the United Nations recognized the reality that street harassment prevents equality during the annual Commission on the Status of Women meeting, a convening of the highest global normative body on women’s rights. For the first time ever, the commission included several clauses about the safety of women and girls in public spaces in its Agreed Conclusions document. The conclusions expressed “deep concern about violence against women and girls in public spaces, including sexual harassment, especially when it is being used to intimidate women and girls who are exercising any of their human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

The U.N. called on its member states “to increase measures to protect women and girls from violence and harassment, including sexual harassment and bullying, in both public and private spaces, to address security and safety, through awareness-raising, involvement of local communities, crime prevention laws, policies, and programs.”

A Tool to Intimidate

Harassment can be used as a tool to intimidate people, to make them leave and give up. As women strive to gain equal rights worldwide, some men harass them to try to keep them from advancing, to prevent their equality, and to try to force them to retreat to their homes. In countries like Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, for instance, groups of men have harassed and stripped young women wearing clothes that the men deemed inappropriate. “Public strippings represent the front lines of a cultural war against women’s advancements in traditionally conservative but rapidly urbanizing societies. They aren’t really about what women are wearing. They are much more about where women are going,” wrote Sisonke Msimang, a South African columnist, in a January 2015 op-ed for The New York Times. After describing the advances African women have made in education, employment, and political leadership in a short amount of time, she said, “Street harassment is often a sign of deep-seated resentment of women’s changing status in society. For men who were raised to believe that they are entitled to be breadwinners and receive sexual gratification and domestic subservience from women, the shift hasn’t been easy.”

Girls who attend school sometimes face backlash for doing so. A famous example is when the Taliban shot 15-year-old Pakistani schoolgirl Malala Yousafzai on her way to school in 2012 because she was an outspoken advocate for girls’ education. She survived the attack and continued her advocacy, particularly for girls’ education in Pakistan, which has the world’s second-highest number of children out of school.

Spectrum of Violence

Street harassment is also a harmful and serious social ill because it falls along a spectrum of violence. It can start as verbal harassment and escalate to sexual assault and rape—and even murder. In the U.S. national street harassment survey conducted by GfK and commissioned by SSH, for instance, 23 percent of women and 8 percent of men said they had been sexually touched by a stranger in a public space, and 9 percent of women and 2 percent of men had been forced by a stranger to do something sexual. Overall, more than two-thirds of harassed women (68 percent) and 48 percent of harassed men said they were concerned their experiences of harassment would escalate. This fear of escalation also encompasses a not uncommon concern that a harasser may pull out a knife or gun and then might use it, in large part because this occasionally does happen. In a 1991 article, scholar Elizabeth Arveda Kissling called street harassment a form of sexual terrorism because one never knows when it may happen—or how far it may escalate.

Street harassment also relates to violence because it can cause re-triggering and be especially upsetting for rape survivors. Researchers at the University of Mary Washington found that sexual harassment is traumatizing for women, especially for those who have experienced sexual abuse. “Women who experienced frequent sexual harassment displayed signs of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Those who had a history with sexual abuse endured a greater degree of trauma, regardless of how often they were harassed.”

The impact of street harassment on women is the focus of Chapter 6 of the Stop Street Harassment book.

The 811 women who took the 2008 Stop Street Harassment survey said they do the following because of actual of feared harassment.

Behavior that could be categorized as staying “on guard” was the most common. At least monthly women:

Constantly assess their surroundings – 80% (62% said always)

Avoid making eye contact – 69% (32% said they always do this)

Purposely wear clothes to attract less attention – 37% (10% always)

Talk or pretend to talk on a cell phone – 42% (10% always)

Next, behavior that limits access to public spaces was most common. At least monthly women:

Cross street/take other route – 50% (16% said always)

Avoid being out at night/after dark – 45% (11% always)

Avoid being out alone – 40% (8% always)

Pay to exercise at a gym instead of outside – 24% (11% always)

Most alarming was how street harassment prompted some women to make a significant life decision:

Moved neighborhoods (at least once) because of harassers in the area – 19%

Changed jobs (at least once) because of harassers along the commute – 9%

(Read SSH Founder’s Forbes.com article about why employers should care about street harassment and what they can do about it)

From anecdotes and women’s stories, it’s clear that street harassment also impacts women’s:

Hobbies and career choices;

Decision to go to evening networking events, night classes, political forums, and go on business trips;

Ability to go to restaurants or movie theaters alone;

Finances when women “choose” to pay for taxis rather than walk or take public transportation, drive their car short distances, pay to exercise at a gym rather than outside, pay for a more expensive hotel in a city center while traveling, pay for room service rather than go out to eat when on a business trip;

Ability to go places without a male escort who often can help keep harassers at bay by showing a woman is “owned” or “spoken for”;

Desire to be nice to strangers because they never know which one will turn into a harasser.

Individually, any one of these strategies and restrictions may not seem like a big deal. Collectively, however, the long list of ways women tend to change their lives is extensive.

The ways most women are told to and “choose” to restrict their lives are myriad and often so ingrained that we may not even realize why we do them anymore. Instead of universal outrage about this as a human rights issue, most men live in ignorance and most women try to adapt and usually live more restricted lives.

This must end.

More:

* Christian Science Monitor, “Street harassment of women: It’s a bigger problem than you think”

* The Guardian, “Feeling harassed? Do something about it”

* Ms. Magazine Blog, “A High Schooler Speaks Out on Street Harassment”

* Rookie Magazine, “It Happens All the Time”

* Medium.com, “Five Reasons Why Street Harassment is Serious” (en español)

Because there is still a lot of discrimination and prejudice against LGBQT individuals, especially transgender individuals, harassment, assault and even murder is a regular fear and experience for them when they are in public spaces and visibly “out.” Each year those who have been murdered are remembered during the November 20 Transgender Day of Remembrance.

There is a small body of information about the effects of street harassment on these individuals and why stopping street harassment against them matters.

* In a survey of 93,000 LGBQT individuals in the EU, one-half of all respondents said they avoid public places, two-thirds avoid holding hands when in public, and four-fifths frequently overhear jokes being made at the expense of LGBT individuals.

When they were asked, “Where do you avoid being open about yourself as L, G, B or T for fear of being assaulted, threatened or harassed by others?” respondents reported the highest levels of fear in public spaces (restaurants, public transportation, streets, parking lots, parks, and other public premises) and lower (though still significant) levels at home, work, and school. Similarly, respondents overwhelmingly identified the “street, square, car parking lot / public place” when asked where their most recent incident of physical/sexual attack or threat of violence occurred.

* When Patrick Ryne McNeil surveyed 331 gay and bisexual men around the world about their experience with street harassment for his master’s thesis, about 90 percent said they are sometimes, often, or always harassed or made to feel unwelcome in public spaces because of their perceived sexual orientation.

* 71 percent reported constantly assessing their surroundings when navigating public spaces.

* 69 percent said they avoid specific neighborhoods or areas

* 67 percent reported not making eye contact with others

* 59 percent said they cross streets or take alternate routes