Cross-posted from Bristol Zero Tolerance

By Dr. Jelena Nolan-Roll

“One that sticks in my mind is when I was quietly eating a burger by the fountains in central Bristol at the end of a night out. A bloke came up and started harassing me and when he did not get the response he wanted (and I remained polite throughout) he grabbed my food and threw it across the square before stalking off. I felt very angry that there was no protection for me against someone stronger stealing from me, no help from the law. I was sure that even if a policeman had been nearby they would have dismissed it as the usual rough and tumble of a night out.”

Bristol Street Harassment Project survey respondent

Bristol was recently dubbed the best place to live in the UK. On a first glance, it has much to offer: breath-taking views, pirate stories, underground tunnels as well as the likes of Wallace and Gromit. However, if you are a woman considering a move to here, you should ask yourself how you feel about being harassed on the street as this is also a common occurrence in this top city as well.

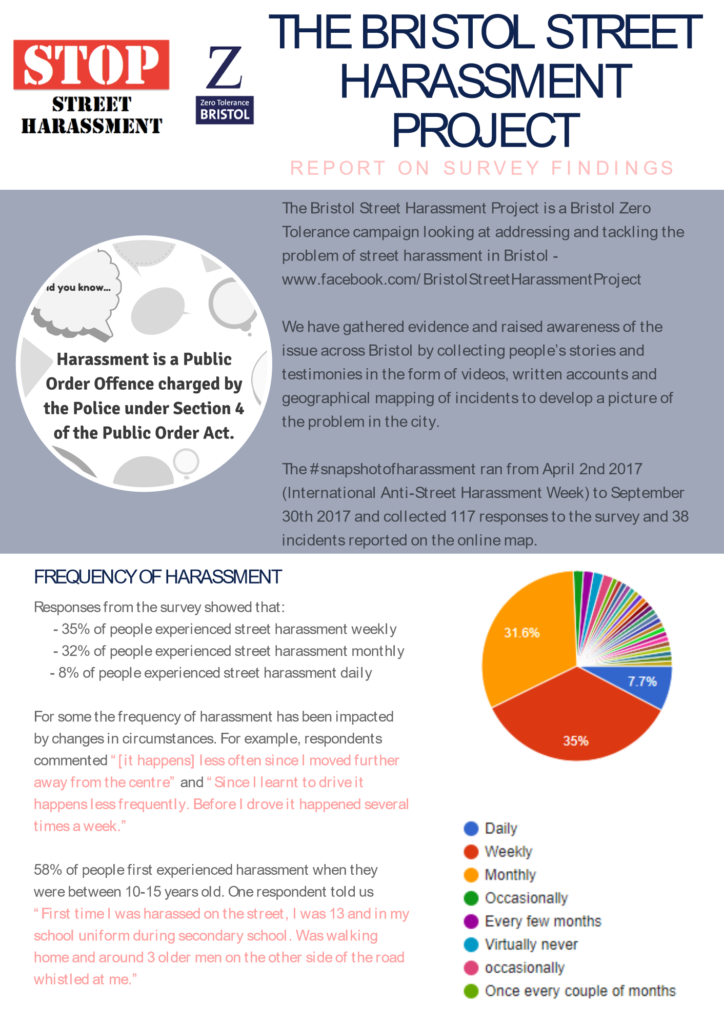

Bristol Zero Tolerance understands gender-based harassment as unwanted comments, gestures, and actions forced on a stranger in a public place without their consent, and directed at them because of their real or perceived gender (whether male, female or non-binary). This type of harassment often takes place in public spaces, and in order to tackle this, the Bristol Street Harassment Project survey (BSHS) was created. More than 100 respondents have completed the survey in order to help explore the incidences and stories about street harassment in Bristol. It has unearthed many important issues- from geographical points where harassment is most likely to happen to specific stories of incidents.

Bristol Zero Tolerance understands gender-based harassment as unwanted comments, gestures, and actions forced on a stranger in a public place without their consent, and directed at them because of their real or perceived gender (whether male, female or non-binary). This type of harassment often takes place in public spaces, and in order to tackle this, the Bristol Street Harassment Project survey (BSHS) was created. More than 100 respondents have completed the survey in order to help explore the incidences and stories about street harassment in Bristol. It has unearthed many important issues- from geographical points where harassment is most likely to happen to specific stories of incidents.

In order to get a deeper insight in to the specifics of street harassment in Bristol, as well as to honour the bravery of those who have experienced it we have analysed these responses.

To start with, they tell a story about the harassment which knows no boundaries be it:

- Gender – “As a trans non-binary person, I recently had 2 men shoulder-barge me in the chest”; ”A woman reported she was approached, questioned and followed by two men on the Lawrence Hill underpass on a light evening recently”; “A woman grabbed my testicles.”

- Age – “First time I was harassed on the street, I was 13 and in my school uniform during secondary school”; “It’s happened since I was about 12 and been non-stop for the last 9/10 years”; “three days ago I was touched inappropriately by a young boy who wasn’t more than 15 years old. I’m 32.”

- Time of day – “I was shouted at, at 10am on a public street.”

- Or even the speed someone is moving at – “While running I was followed by a man”; “I was riding my bicycle in St Pauls when a man in a white van started shouting – hey there, sexy legs, sexy legs! I ignored him and he shouted louder and louder and then noticed there was a child in the vehicle and they started laughing”; “Mainly being shouted at in the street when on my bike – either derogatory comments about my weight or sexual comments. I have also been grabbed by men reaching out of car windows whilst I cycle.”

That is not to say that the harassers should restrict their comments to a certain age group, part of the town or time slot, but that the tide of their privilege washes across many shores with absolutely no regard to the local ecosystem. This is quite problematic.

Research has shown that harassment for a victim can have a plethora of negative psychological and emotional consequences, such as fear, anger, distrust, depression, stress, sleep disorders, self-objectification, shame, increased bodily surveillance, and anxiety about being in public. Therefore, by performing the act of street harassment the harasser makes public spaces feel unsafe for the victim and so excludes the victim from actively participating in that community with their voice. It is the voices and the stories that do not have a problem with harassment that stay dominant and are heard loudest.

According to the survey responses, this is how some of them do it:

Objectification

“I was riding my bicycle in St Pauls when a man in a white van started shouting – hey there, sexy legs, sexy legs! I ignored him and he shouted louder and louder and then noticed there was a child in the vehicle and they started laughing.”

Bristol Street Harassment Project survey respondent

“Sexual objectification doesn’t get oppressive until it is done consistently, and to a specific group of people, and with no regard whatsoever paid to their humanity. Then it ceases to become about desire and starts to be about control. Seeing another person as meat and fat and bone and nothing else gives you power over them, if only for an instant. Structural sexual objection of women draws that instant out into an entire matrix of hurt. It tells us that women are bodies first, idealised, subservient bodies, and men are not.”

Laurie Penny ‘Unspeakable Things: Sex, Lies and Revolution’ 2014

Based on the responses in BSHS, the harassers consistently and constantly objectify their victims: “I was followed up Park Street by a group of about 8 men who were out drinking. They were all commenting on how I looked ‘alright’ and how they should take me with them”; “a large group of men in their mid/late 30s (drunk) started shouting at me and my friend whilst walking towards us, they were making hand gestures and specifically targeting me, making comments about my clothes and body”. Most of the harrasers’ seem to be not aware of consequences. “It is just a game we lads play when we go out, innit?”

No it is not.

Feminist theory has shown how objectification leads to women feeling self-conscious about their body which in turn can bring about a host of issues. For example, being regularly reminded that the physical features you have are the most important aspects of you or that these do not align with what society considers ‘ideal’, is being regularly reminded of how, essentially, worthless your other qualities are. Goodbye, wonderfully complex person you spent ages developing and working on. Hello, self-depreciation, shame and anxiety. And then the victim moves deeper into herself, and away from the public space. Inequality wins again.

In addition to this, research also shows that street harassment increases self-objectification (Lord, 2009). When objectification is internalised and turns into self-objectification, it can also be a contributing factor in developing mood and eating disorders (Greenleaf and McGreer, 2006; Moradi, Dirks and Matteson, 2005).

So while boys play, girls tremble in terror. While a frightened person with potential mental health issues (like mood or eating disorders) will find it that much harder to be on the front lines of social change – so the vicious circle keeps spinning.

Another facet of the problem is that society is getting used to this kind of behaviour and normalises it.

Normalisation of street harassment

“Street harassment isn’t just annoying. It is scary and traumatising. Nonetheless, it has been accepted as everyday reality.” (Read and May in Kearl, 2010)

“Living with street harassment means… accepting assault and disrespect as normal” (Cathy Ramos, in Paludi and Denmark, 2010)

Responses also show the normalisation of street harassment in Bristol. For example: “My 13 year old daughter gets whistled at on a regular basis (in her school uniform)”; “A drunk man in his late 30s came and talked to me when I was sitting on the grass in Castle park. He was with 2 other men. I politely but firmly told him I wanted to continue reading yet he insisted on staying and talking. I then told him I wasn’t interested and he brushed me away with a hand gesture calling me something I didn’t understand but which made his friends laugh”.

Normalisation of street harassment takes place, among other factors, because street harassment itself serves as a powerful bonding tool for certain types of men, who often represent a dominant voice in society. Indeed, research has consistently shown that the reasons men engage in catcalling or objectifying women are to do with “feeling of youthful camaraderie” (Benard and Schlaffer, 1984:71) and male social bonding practices (Wesselmann and Kelly, 2010; Quinn, 2002).

On the other side – the victim side, this means living in fear of going to certain public places (i.e. in 1981 Riger and Gordon surveyed women in three cities, finding that a fear of violence severely restricted many women’s movements in public), anxiety when walking home alone and learning from adolescence (71% of women in UK have been harassed before the age of 17 as an international survey on street harassment shows) that the fear and sexuality go together. This seems like a very high price to pay for the group of mates to become closer.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t end there.

Responses to harassment

“I felt like I had no option but to engage with him as I was afraid of his reaction and walked away feeling annoyed and frustrated that this had happened.” Bristol Street Harassment Project survey respondent

“On my way back to City of Bristol College Green after going to Greggs for lunch a man spat at me. I proceeded onward like nothing had happened and then cleaned off the Phlegm with some toilet roll in the College bathroom.” Bristol Street Harassment Project survey respondent

“One sure test of social privilege is how much anger you get to express without the threat of expulsion, arrest, or social exclusion.” Laurie Penny ‘Unspeakable Things: Sex, Lies and Revolution’ 2014

Due to the different raising patterns of girls and boys, where boys are the heroes of their own stories and girls are often a supportive character (Penny, 2014), most of the victims either do nothing or very little as a response to being harassed, often due to the fear that the situation will escalate or because they were simply taught that ‘good girls’ do not make a fuss. Unfortunately, good girls also make good victims – ones who just ignore when they are catcalled, do not respond back and are seen but not heard.

The departure from that sort of behaviour for a woman is often deemed newsworthy – for example, a woman who takes selfies with the harassers. Whereas this is a very creative and intelligent idea, it still occurs post hoc and doesn’t tackle the harassment per se, and not to mention that not all of the girls who get harassed are so brave.

For there is fear as well. Fear that they will be physically assaulted, fear that there will somehow be repercussions to them being victimised but also fear that they will not be taken seriously and that their concerns will be dismissed as something inconsequential. This fear is well justified, judging by the rage and anger of harassers who are stood up to (How dare she?!), but also by the internal belief of victims of abuse that the authorities will do nothing to protect them. One of the respondents explains it well:

“You are so objectified by these men that if you veer from their idea of an object, i.e. you fucking speak, their only response is pure confusion which within seconds becomes rage, how very fucking dare I speak when I’m being harassed?! Now you’re really going to get it. Now I don’t say anything and I hate myself for that because it feels so weak and voiceless.”

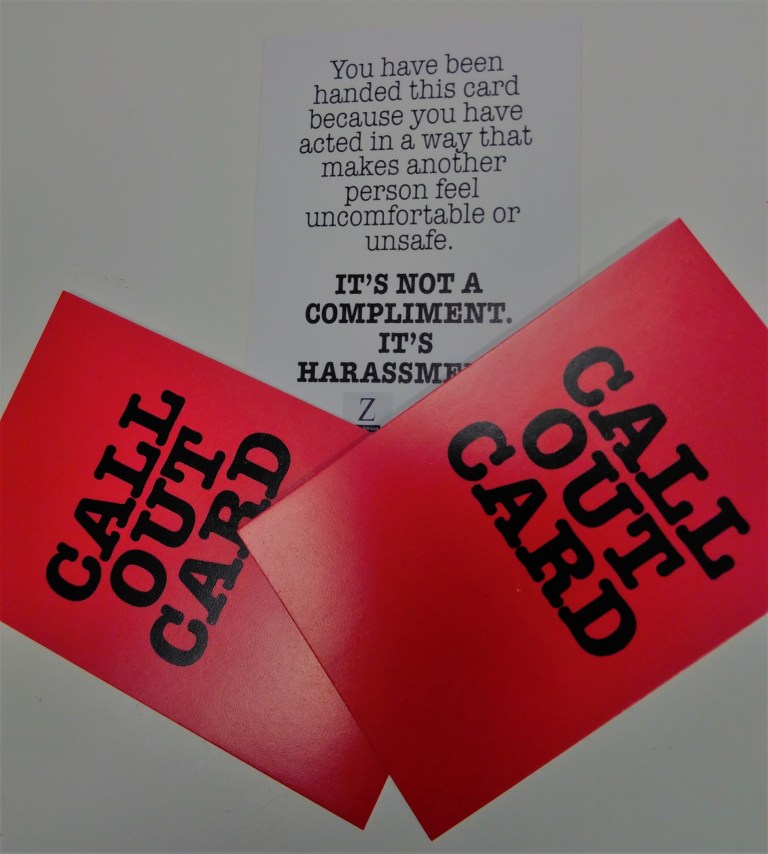

This is also evident in the responses of people who chose not to use the Call out Cards developed by Bristol Zero Tolerance as a way to address street harassment in a nonviolent way. When asked why they would not use them, many respond that it is out of fear of escalation or being ridiculed. For example: “Surely it would only inflame the situation, putting me in more danger, and would mean nothing to the harasser.”

This demonstrates even further the scope of normalisation of harassment and the ways the experiences of those on the receiving end are laced with fear and shame. Those who are doing the harassing do it with a conviction that it is somehow acceptable to objectify and catcall.

So they keep doing it.

Consequences of harassment

“[Harassment] was very, very intimidating, and made me feel insecure about wearing leggings / gym wear outside of the gym.” Bristol Street Harassment Project survey respondent

“I ended up borrowing my partner’s car and choosing a longer (more expensive) driving commute just to avoid [harassment] and continued to do this until I no longer needed to commute.” Bristol Street Harassment Project survey respondent

Interestingly, the most reported emotion in response to the harassment was anger. Whereas in most men the anger would lead to confrontation, be it verbal or physical, when it comes to victims of street harassment the reaction is quite the opposite. This again shows different ways boys and girls are socialised and taught to respond to anger. As the violence expert Rory Miller states: “Women are used to handling men in certain ways, with certain subconscious rules – social ways, not physical ones. These systems are very effective within society and not effective at all when civilization is no longer a factor, such as in violent assault or rape.” (Miller, 2008. 48)

Many women alter their behaviour as a consequence of experiencing street harassment. Changes range from choosing a different route home to moving away, like perfomer China Fish did after she had enough of being catcalled and abused on Bristol streets. Behaviour alterations are rarely, if ever, towards a more positive and fulfilled lifestyle. Those reported in BSHS are always towards a behaviour of avoidance – of certain streets, of certain clothes, or certain modes of transportation (i.e. a bicycle). And as we know, avoiding the problem does not solve it, unfortunately.

Many women alter their behaviour as a consequence of experiencing street harassment. Changes range from choosing a different route home to moving away, like perfomer China Fish did after she had enough of being catcalled and abused on Bristol streets. Behaviour alterations are rarely, if ever, towards a more positive and fulfilled lifestyle. Those reported in BSHS are always towards a behaviour of avoidance – of certain streets, of certain clothes, or certain modes of transportation (i.e. a bicycle). And as we know, avoiding the problem does not solve it, unfortunately.

Conclusion

“Recognising gender as an aggravating factor in hate crime is a huge step towards ensuring the streets and homes we live in are free from prejudice.”

Avon and Somerset Police lead for Hate Crime, Superintendent Andy Bennett

Whereas Bristol may well be seen as one of the top ten cities to live in the UK, if you are a potential victim of street harassment, the results of the Bristol Street Harassment Survey indicate that you would probably be better off moving elsewhere or brushing up on your self-defence skills.

Responses to the question about a specific incident of street harassment paint a picture where harassers (who are mostly men, but there was one woman as well) objectify the victims in an atmosphere which normalises the harassing behaviour. This leads to feelings of shame and fear in victims and results in behaviour changes, mostly on the scale of avoiding certain places or changing one’s dressing style in the hope that the harassment won’t take place.

At the core of this kind of harassment is a power dynamic that constantly reminds historically subordinated groups of their vulnerability to violence in public spaces and also reinforces the sexual objectification of these groups in everyday life. If this happens in a European Green Capital and one of top ten cities to live in the UK, what kind of situation do you think happens in less open spaces?

Dr. Jelena Nolan-Roll is a researcher at Association of Employment and Learning Providers.

My name is China Fish and like many women, I have experienced frequent and unwanted sexual harassment as I walk our city streets. In 2010 I created a satirical performance about this very subject called ‘Lucky Saddle’, two words shouted at me by a man as I cycled in Bedminster when I was around 21 years old. It is an issue close to my heart, as, like most humans, I desire to be able to move freely and safely through the world I inhabit.

My name is China Fish and like many women, I have experienced frequent and unwanted sexual harassment as I walk our city streets. In 2010 I created a satirical performance about this very subject called ‘Lucky Saddle’, two words shouted at me by a man as I cycled in Bedminster when I was around 21 years old. It is an issue close to my heart, as, like most humans, I desire to be able to move freely and safely through the world I inhabit.

Take action in Bristol!

Take action in Bristol!