By @MsEntropy

Lauren Wolfe, founder of the project Women Under Siege, issued a recent call to declare 2013 as the year to end rape. The comments to her CNN post prove revealing—more than a decade into the twenty-first century, the discourse that facilitates rape culture is alive and well. Wolfe’s activism predates the horrific gang rape of Indian university student Jyoti Singh Pandey, but press coverage of the atrocity, and the debates it stimulated demonstrate that we—globally—have a long way to go.

Spiritual leader Asaram Bapu posthumously chastised the gang rape victim, Jyoti Singh Pandey, arguing that she should have grasped the hands of her attackers, called them “brother,” and begged them to salvage her “dignity.” A defense attorney for those accused in the Delhi attack, which resulted in the death of the young woman, recently declared that the victim was “wholly responsible” for her actions, as “respectable ladies” allegedly don’t get raped. In the wake of protests against this vicious assault, debates began spreading like wildfire about appropriate punishment, rape prevention and—stunningly—“culture” as an explanation. The recent decision (to many, including myself, questionable) of Egyptian activist Alia al-Mahdy to ally herself with FEMEN has similarly provoked debates on “culture,” sexual mores, and additionally thrown back into the mix assumptions about an alleged linkage between clothing and harassment. Al-Mahdy first came to fame over a nude self-portrait posted on her blog; she later stood naked outside an Egyptian Embassy in Sweden to protest the Islamist nature of the proposed Constitution. Egyptians debated whether or not al-Mahdi’s action merited stripping her of citizenship.

The horrific gang rape in Delhi, and the debates over Alia al-Mahdy’s alliance with FEMEN are not the only arenas in which rape culture, feminism and violence against women merit our attention. For many Americans, we need to look at our own backyard just as much. Remember Senate candidate Richard Murdock’s idea that pregnancy as a result of rape is a “gift from God?” What about Todd Akin’s inflammatory comments about “legitimate rape,” and his claim that women have a mysterious defense mechanism to “shut the whole thing down?” Georgia Representative (and obgyn) Phil Gingrey has appeared in a surreal, belated defense of Akin’s statements.

As a woman who has lived in the United States, France, Morocco, Algeria, Egypt and Tunisia—I am here to tell you: harassment is ubiquitous. No—it does not matter what we wear. Manifestations of discrimination and sexual harassment may take a variety of forms, but the all-too often unacknowledged abuse of power dynamics does not.

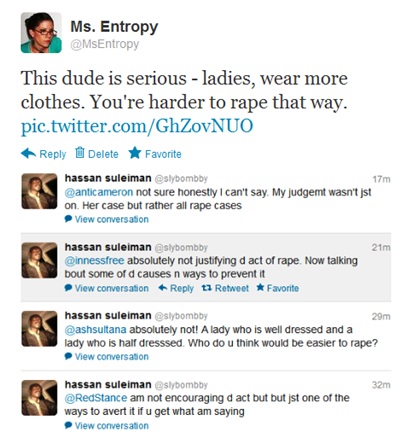

In light of all of these news stories, I decided to tackle one aspect to the discourse around rape culture, namely, the idea that what one wears matters in terms of drawing or repelling sexual assault and or harassment. Although I usually use Twitter as a mechanism for commentary on Middle Eastern and North African political affairs, I was prompted to take on this aspect of rape apologism when I came across the following series of Tweets:

Twitter user @slyombby does not appear to be cognizant of the manner in which the “clothing” debate feeds into rape culture; in his mind, he is not passing “judgment,” but rather—discussing what he feels is a fact: that more clothes somehow means more protection from assault. This is, frankly, simply not the case.

In response, I posted a series of Tweets to my own account with the caption, “I was sexually harassed/assaulted wearing this. Was it my clothing? #EndSH.” The five pictures included a spectrum of clothing, worn in different countries, at different ages in my life—ranging from a baby photograph to a recently taken image:

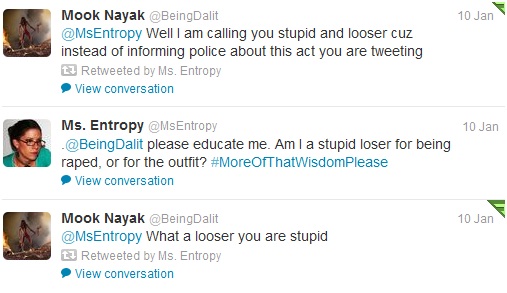

To be fair, I received several heartening responses from both women and men. Some eagerly took the idea that “clothing matters” to task; others seemed shocked at the question—and failed to detect the irony and sarcasm behind it. However, responses such as the following firmly convinced me that we—women and men—urgently need to debunk the myths that sexual violence can be correlated with clothing, and that it is a phenomenon uniquely facing women:

Twitter user @BeingDalit attacked me as a “stupid looser” [sic] for discussing my personal history, rather than going to the police (an assumption entirely of his own making). He went on in a later exchange to accuse me of seeking attention, although how a mention of childhood sexual abuse fits into that, I’m not entirely clear. This accusation, however, does merit a brief analysis.

For both men and women who have encountered sexual violence and harassment, speaking out is a difficult action. This is particularly the case for male victims, who are often far more reticent to relate their own experience of trauma.

I would like to call on others—critically, men and women—to post similar photos using the tagline, “I was sexually harassed/assaulted wearing this. Was it my clothing? #EndSH.” If you feel more comfortable blurring your face, do so. I do, however, think contributions from both genders, in a variety of cultures and spanning the range of clothing choices can make a difference. Refuse to take the shame of others as your own, and no—it is never, ever what you wear.