Mariel DiDato, NJ, USA, SSH Blog Correspondent

“Hold on” You may have thought to yourself after reading the title of this article, “I’ve told my sisters that they throw like ‘girls.’ It was just a joke. It has nothing to do with sexual violence.”

Directly speaking, no, it doesn’t have to do with sexual violence. However, telling a kid that they “(insert verb here) like a girl” is saying to that kid, boys are better at that thing than girls, and that they should emulate boys if they want to be good enough.

Or quite possibly, you thought, “Woah! I’ll tell a woman she’s sexy if I see her on the street, but I wouldn’t rape her.”

Fair enough. A street harasser may not ever think to rape someone, but somewhere along the line, they were taught that it is normal and acceptable to disregard a woman’s comfort so that they could tell her how sexy she is. Maybe someone else takes it a step further and follows a woman, demanding her attention. The next person might take it one step further and grab a woman inappropriately on a crowded street or bus. The next might become violent upon rejection, because his right to her body is more important than her right to say no. The line between any of these acts is a fine one, especially if they take place on a regular basis.

Ever ask for a woman’s number and then threaten to call it before she leaves to make sure she put in the correct number? Ever think that maybe she doesn’t want you to have her number?

Ever pressure a woman to have sex after multiple “No’s” or “I don’t want to’s,” for her to finally give in? Ever think that maybe she doesn’t want to have sex and that she’s either tired of saying “no,” or afraid of what you’ll do if she doesn’t eventually say “yes”?

Rape culture isn’t a myth that the progressive left came up with to place blame on men who have never committed sexual violence. It’s a term studied and used by professionals in this field to describe the aspects of society that condone and encourage violence against women.

“Woah, hold it!” You might be thinking, “Rape is one of the worst crimes someone can commit! Our society doesn’t condone rape!”

Stay with me, and just hear me out. It’s a more complicated idea than that.

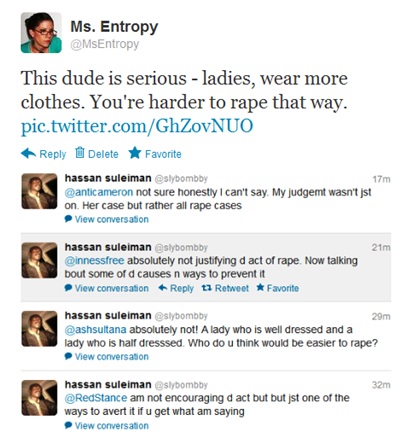

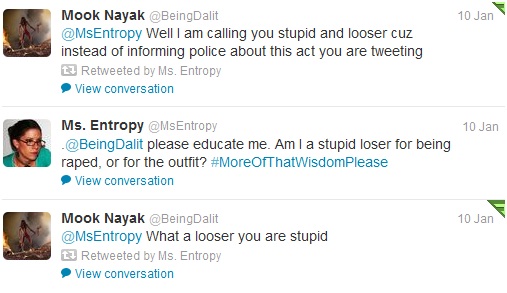

The violence pyramid is the concept that sexual violence wouldn’t be so prevalent if sexual harassment wasn’t condoned. In addition, sexual harassment wouldn’t be condoned if sexist attitudes weren’t taught from childhood. From “You throw like a girl!” to “Nice tits, sweetheart!” to “She shouldn’t have gotten drunk if she didn’t want to be raped,” these themes are connected. Victim-blaming, refusal to believe survivors of sexual assault, and physical manifestations of sexual violence cannot proliferate without first building the primary bases of sexism. If boys are just naturally better and more valuable than girls, boys’ desires must be more valuable than girls’ comfort. If young boys see men harassing women in public, maybe it’s okay to harass girls at school in the hallways. If the people around boys make jokes about sexual assault, and blame victims of rape more than abusers, maybe committing rape isn’t even such a big deal to begin with. And if all of this is something that “only happens to girls,” what happens when a male becomes a survivor of sexual assault?

If sexual assault is the victim’s fault because “Some people are just psychopaths. You can’t prevent it. You can only take measures to protect yourself,” why are rape and molestation far more common than murder? If society truly believed that sexual violence is truly only committed by “psychopaths,” why are we quick to ignore the acts of Nate Parker, R. Kelly, and so many more abusers in favor of their careers? Is it any wonder that convicted rapists such as the infamous Brock Turner, and more recently Austin James Wilkerson, received laughable sentences for committing a serious felony? Society is quick to decry the effects of rape culture, but quick to deny its existence. We need to acknowledge the ugly parts of our society that allow for these occurrences to be so commonplace and unpunished.

Throw out the ideas that men should be sexually dominant and promiscuous, and women should be sexually inexperienced and submissive, that it’s okay for boys and men to shout sexually charged “compliments” to women in public, and that men are entitled to women’s time, attention, and sexuality. Replace these with the concept that rejection is okay, and shouldn’t be met with persistence. Reinforce the fact that people on the receiving end of harassment and assault are never at fault. Stress to young children that doing anything “like a girl” is just as good as doing it “like a boy.” We can only work towards long-term solutions if we acknowledge the root of the problem. It’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks, but it’s easier to teach young children that all people, regardless of demographic, are worthy of respect.

Mariel is a recent college graduate, feminist, and women’s rights activist. Currently, she volunteers for a number of different organizations, including the Planned Parenthood Action Fund of New Jersey and the New Jersey Coalition Against Sexual Assault. You can follow her on Twitter at @marieldidato or check out her personal blog, Fully Concentrated Feminism.