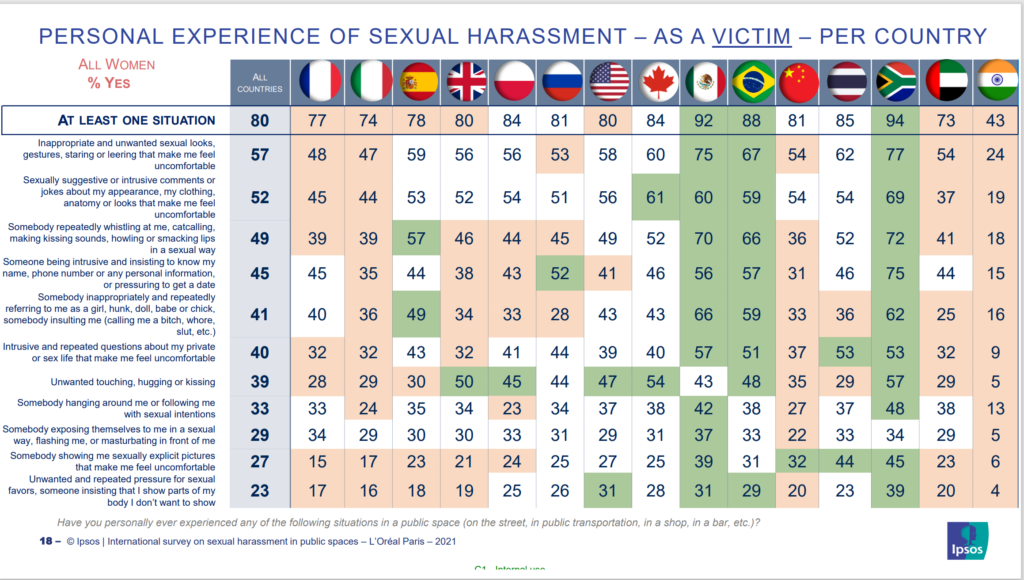

L’Oreal Paris, one of our partners for this year’s International Anti-Street Harassment Week, recently released the results of a 15-country study on street harassment. With survey firm IPSOS, they surveyed a representative sample of around 1,000 women in each country between Jan. 25th – Feb. 9th, 2021, so the results represent approximately 15,000 women’s experience.

First, the results confirm once again that this is a pervasive and global problem! Around 80 percent of women across the 15 countries said they’ve experienced street harassment (with the highest figures coming from South Africa – 94% and Mexico – 92%).** The countries included in the survey were: Brazil, Canada, China, France, India, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Spain, South Africa, Thailand, UAE, UK, and USA.

The results also show how much this violation continued during the past year of the COVID-19 pandemic, even with all the quarantines, lockdowns, social distancing, and increase in working and going to school remotely that came with it. Around one in three women (31%) said they faced street harassment last year. This figure is 46 percent for those ages 18 to 34. Additionally, 42 percent said they witnessed street harassment occur in the last year.

Thinking about the last year, 50 percent of respondents said they did not feel safe in public spaces! Among these women, reasons they gave for feeling unsafe included: not being able to see people’s faces behind masks (51%), there are fewer people around (36%), and shops are closed (10%).

75 percent said they avoided certain public spaces to try to avoid street harassment and 54 percent said they avoided some forms of public transportation specifically.

A unique feature of being in public spaces this past year is that many or most people wore masks. This did not help the situation of street harassment. Instead, 72 percent of women felt harassers were emboldened to harass because of the increased anonymity a mask gave them.

It is clear that street harassment continues to affect so many women’s lives in really significant and scary ways — the murder of British woman Sarah Everard while she walked home last month emphasizes this reality too.

L’Oreal Paris is partnering with Hollaback! to host free bystander online training sessions called Stand Up! to help combat this widespread problem. Check out the programs being offered this week and join one if you can!

** This survey only focused on women, ages 18 and up, and if teenagers and pre-teens were included and persons of all genders from the LGBTQ community and other targeted communities, I’m sure these figures would be even higher.

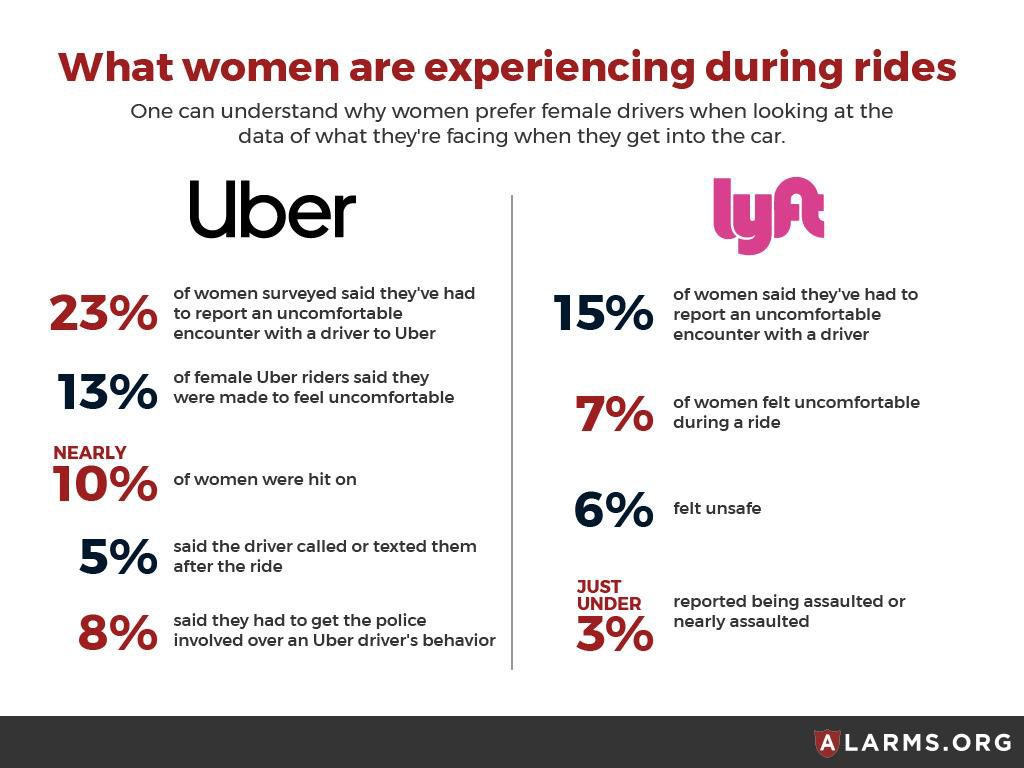

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) in public transport and its associated spaces has and continues to be a global problem. According to the

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) in public transport and its associated spaces has and continues to be a global problem. According to the