Eve Aronson, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, SSH Blog Correspondent

What’s in a word? In a character?

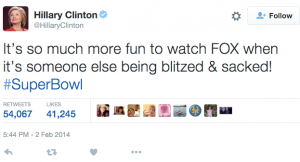

During last February’s Super Bowl Sunday in the US, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton found out.

With her excruciatingly ordinary tweet about American football and politics, Clinton unintentionally showed the power of 140 characters broadcast to 4.9 million vaguely- connected social media followers.

With her excruciatingly ordinary tweet about American football and politics, Clinton unintentionally showed the power of 140 characters broadcast to 4.9 million vaguely- connected social media followers.

According to blogger Bridget Coyne, the tweet was retweeted over 57,000 times and prompted 33,600 new followers, ten times Clinton’s average daily follower growth.

While there are plenty of social media critics out there (and there are many), there is no denying the powerful potential of social media platforms to provoke engagement and build interest in everything from funny cats to presidential debates.

In the sphere of anti-street harassment, social media is being used to not only quickly broadcast people’s experiences but to connect and empower folks with shared experiences.

Not unlike Clinton’s wildly popular tweet, more and more people are engaging with social media platforms like Twitter, and important issues like street harassment are gaining some serious momentum.

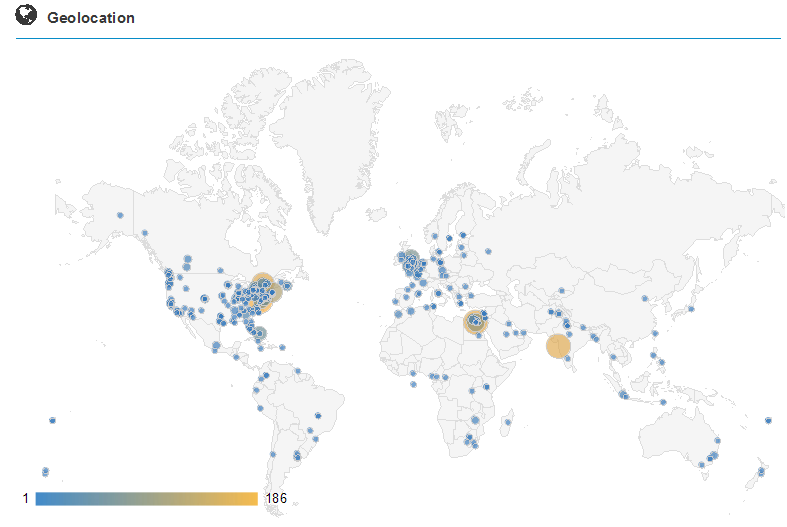

The figure below maps the global conversation about street harassment using the hashtag #endSH from 2014-2015:

(Source: Followthehashtag 2015)

With a reach of over 13 million, the above map speaks not only to global experiences of street harassment, but also to individuals around the world collectively exposing the phenomenon and, in doing so, working to unsettle and resist the power structures that sustain it.

Towards Sousveillance

We can also look at simple actions like tweeting as a means to empower those targeted in street harassment interactions— like women of all backgrounds and people of color or LGBTQ folks of all genders— by turning what is conventionally known as the “gaze” back onto harassers.

This practice of using social media to do this— either by sharing a story, an opinion or by offering virtual support to someone else posting about their experience— is what is called “sousveillance”.

Coupled with digital technologies like mobile phone apps, geo mapping or online platforms for sharing experiences about street harassment, what ‘sousveillence’ does is put the ball back into the court of the individual who experiences street harassment.

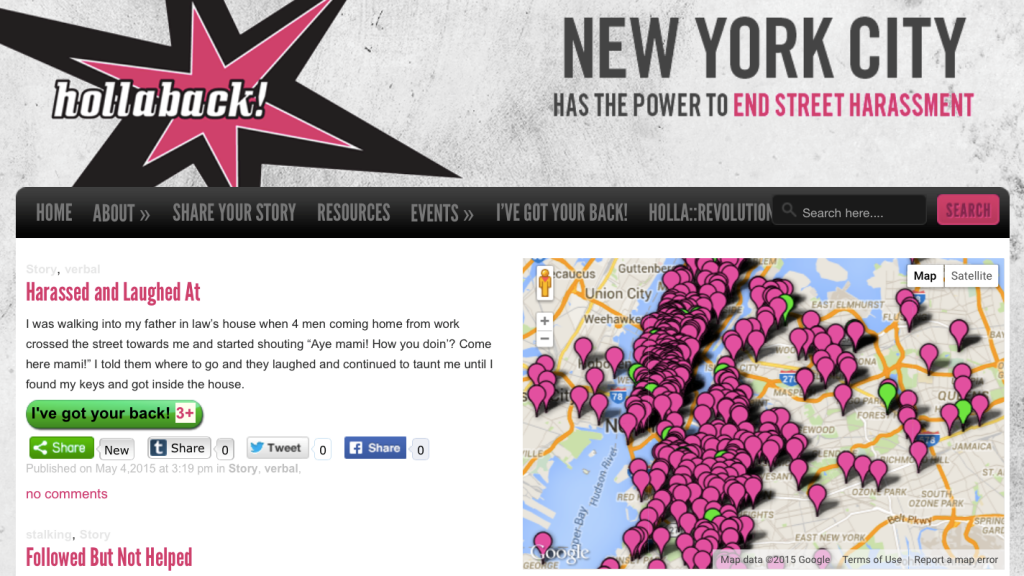

We can see in the map below how, for example, Hollaback! New York embeds geo mapping into its site to “sousvey” harassers as well as to visualize and map bystander presence. On the map, red dots represent reports of street harassment, while green dots represent individuals reporting bystander presence:

(source: Hollaback! NYC)

The image above isn’t just a bunch of red and green dots— each dot represents an experience of street harassment like hissing, leering or groping. And having experienced street harassment and knowing that you’re not along has a greater impact than you might think.

“[I]t makes me feel better to know that there are other women going through the same thing,” stated an anonymous submitter to Hollaback!. “I know I can be a little star on the map for someone else so they know they are not alone either”.

In the Netherlands Online

Although most Amsterdam survey respondents in my research earlier this year had not visited a specific website dedicated to combatting street harassment, almost half have tweeted or posted their thoughts or experiences of street harassment on social media. This finding is huge and signals a need that, for example, engaging more with these technologies could help to fill.

When searching for online platforms and digital technologies in the Netherlands being used to map and resist street harassment, Straatintimidatie (Street intimidation), an online campaign in the Netherlands that is vying for a law against street harassment, was the only online presence that I came across.

Straatintimidatie does not have a space—online or off—for community members to share stories and strategies about street harassment. Nevertheless, the campaign’s Twitter feed has a combined reach of over 52,000 people, which is considerable and indicates that engaging more in online activism about street harassment in Amsterdam and throughout the Netherlands could gain significant momentum with the introduction of more diverse online platforms.

As we saw with the hashtag campaigns above, there are evidently immense pools of people using these online platforms, which can be tapped into in the fight against street harassment in the Netherlands.

If a single tweet like Clinton’s can instantly engage tens of thousands, imagine the disruptive potential of billions of virtual voices— in the Netherlands and beyond— demanding an end to street harassment.

Hashtag activism is not only a lot of people talking; it’s a lot of people talking about specific issues that gain momentum over time and have the potential to effect change on unprecedented scales.

So the next time you sign onto your social media account, get excited. Get excited about the incredible amount of power at your fingertips; the millions of people ready to answer your call to action; and, one character at a time (but not more than 140!); it’s time to turn the tide against street harassment together.

You can find the full analysis of the Amsterdam survey results here or by contacting Eve atevearonson@gmail.com. Follow Eve and Hollaback! Amsterdam on Twitter at @evearonson and @iHollaback_AMS and show your support by liking Hollaback! Amsterdam’s Facebook pagehere.