Each day across the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, we will highlight a 2018 activism effort undertaken to stop street harassment or a personal story about stopping harassers!

Day 3: UK Government Inquiry

A nine-month inquiry into street harassment led by the Women and Equalities Committee caused some MPs to call for the government to address street harassment.

A nine-month inquiry into street harassment led by the Women and Equalities Committee caused some MPs to call for the government to address street harassment.

“Committee chairwoman Maria Miller said: ‘Women feel the onus is put on them to avoid ‘risky’ situations – all of this keeps women and girls unequal.’

The report concluded that social attitudes underpinned sexual harassment, and the normalisation of it contributed to a ‘wider negative cultural effect on society.’

And while the government has pledged to eliminate sexual harassment of women and girls by 2030, the committee said there was ‘no evidence of any programme to achieve this.’

The report outlined seven key recommendations to tackle street harassment:

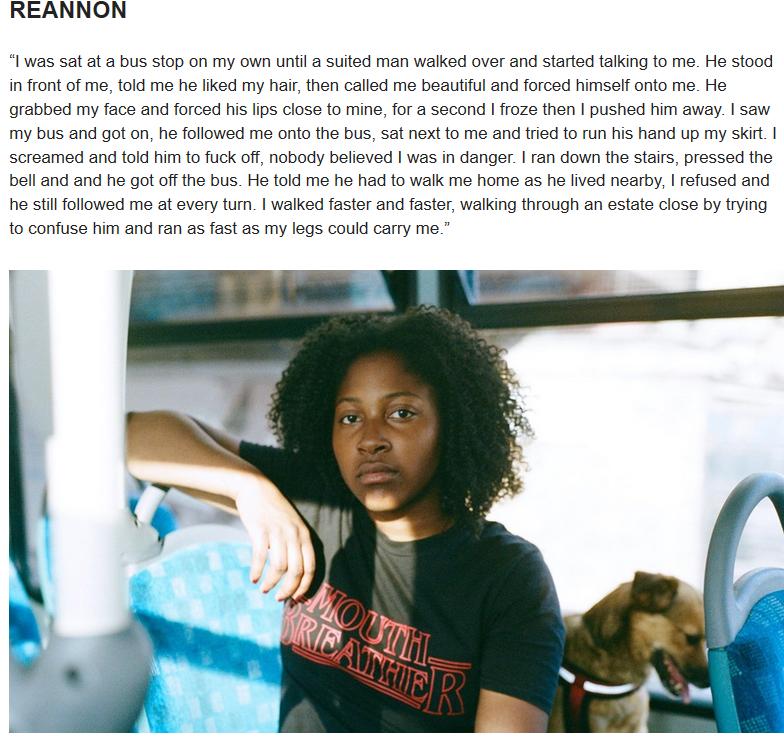

1. Force train and bus operators to take tougher action against sexual harassment and block the viewing of pornography on public transport.

2. Ban all non-consensual sharing of intimate images

3. Publish a new “Violence Against Women and Girls” strategy

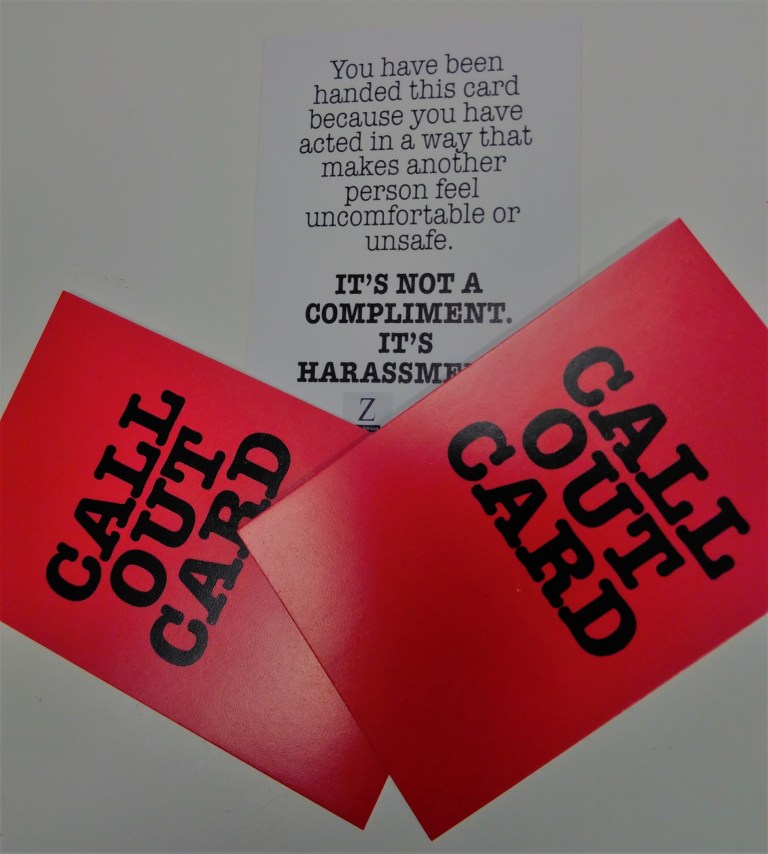

4. Create a public campaign to change attitudes

5. Take an evidence-based approach to addressing the harms of pornography, along the lines of road safety or anti-smoking campaigns

6. Tougher laws to ensure pub landlords take action on sexual harassment – and make local authorities consult women’s groups before licensing strip clubs

7. Make it a legal obligation for universities to have policies outlawing sexual harassment.”

My name is China Fish and like many women, I have experienced frequent and unwanted sexual harassment as I walk our city streets. In 2010 I created a satirical performance about this very subject called ‘Lucky Saddle’, two words shouted at me by a man as I cycled in Bedminster when I was around 21 years old. It is an issue close to my heart, as, like most humans, I desire to be able to move freely and safely through the world I inhabit.

My name is China Fish and like many women, I have experienced frequent and unwanted sexual harassment as I walk our city streets. In 2010 I created a satirical performance about this very subject called ‘Lucky Saddle’, two words shouted at me by a man as I cycled in Bedminster when I was around 21 years old. It is an issue close to my heart, as, like most humans, I desire to be able to move freely and safely through the world I inhabit.

Take action in Bristol!

Take action in Bristol!