Recently, two young Argentinian women, María Coni and Marina Menegazzo, were killed while backpacking in Ecuador. In response to the horrific victim-blaming that followed, the phrase #viajosola (I travel alone) trended on Twitter, with more than 5,000 women using the hashtag to discuss their experiences.

Here’s mine. I have visited 19 countries and all 50 U.S. states (more than 40 of them at least twice) and have traveled alone for many of the trips. I began running alone in public spaces in middle school and I first flew on a plane solo as a teenager. Thus, combined, I have spent a lot of time alone in public spaces locally and while traveling. And yes, I have faced a lot of street harassment. I’m 33 now and I’m sure the figure is in the thousands.

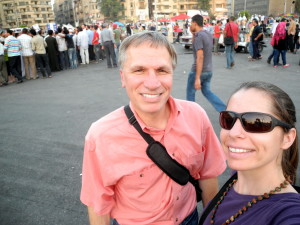

In addition to the scary experiences I’ve had in the U.S. of being grabbed, followed and chased, my worst experiences have been in the UK, Ethiopia, and India. Men made explicit comments to me, followed me, hounded me. I traveled with my dad in Egypt and if I ever left his side for a second in a public space, men would start in with catcalls. I specifically traveled with my dad to try to stay safe, especially as there were still mob attacks happening against women at Tahrir Square.

But I’ve had really wonderful solo travel experiences too, with my best experiences happening in Ireland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden (likely there’s no coincidence that they are countries with some of the highest gender equality rates in the world… it probably also helped that I didn’t look out of place as a white woman in those countries).

I was hesitant the first time I traveled completely alone in Ireland at age 21 while studying abroad. I stayed in hostels full of strangers, had to figure out bus schedules and debated ever eating in restaurants or just picking up snacks at a grocery store and eating on a park bench or hostel room bed. But overall it was a lovely trip. I saw major historic sites and national parks from coast to coast. I even kissed the Blarney Stone. Everyone I encountered was so nice and helpful. In my six days of solo travel I wasn’t harassed once. And I had the freedom to do what I wanted. I determined every aspect of my schedule. I could eat when I wanted, leave when I wanted, go to bed when I wanted, etc.

I wish every person — every woman — could have the experience to travel and to travel safely. To see the world, to meet its diverse people, and to expand their mind. But street harassment and the fear of it escalating to sexual assault and even murder puts a damper on things.

Going back to the two Argentinian women and the victim-blaming, here are excerpts from two excellent articles on the Guardian and NPR:

“The restriction of women’s solo travel remains a curiously acceptable form of victim-blaming. When Sierra was killed, for example, one headline read: “American’s death in Turkey puts focus on solo travel”. Compare this with a headline about the death of Harry Devert, a 32-year-old US citizen killed while travelling alone in Mexico: “The untimely death of world traveler Harry Devert.” When Australian Lee Hudswell died after an accident while tubing down a river in Laos, the press reported: “Fatal end to Lee’s overseas adventure”.

Female travellers have long been subjected to restrictions and double standards, with their gender emphasised over their capability and strength. Female travellers are much more likely to be categorised into reductive stereotypes – such as the glamorous adventuress – than their male counterparts. Think HG Wells in ‘Warehouse 13’, sexy Lara Croft, or the film portrayal of Adèle Blanc-Sec versus that of Tintin. When men travel in films, they are usually just travelling, but when women do, they are often running away from (or towards) a male romantic partner. (Compare The Holiday, Wild, Under the Tuscan Sun, Eat Pray Love, to The Motorcycle Diaries or Into the Wild.) There are, of course, welcome exceptions (take a bow, Dora the Explorer).

Travel has historically been, and to an extent still is, seen as a natural, bold activity for men, and a risky or frivolous pursuit for women. And as with so many other forms of low-level sexism, the knock-on impact is enormous. At a local level, curtailment of travel can prevent women from accessing healthcare, visiting family or taking job opportunities. When we restrict women’s wider freedom, we also curtail their ability to broaden their horizons and acquire valuable language skills. The impact on women’s careers can be clearly seen in the responses to female journalists who experience assaults while reporting abroad and face not only immense victim-blaming but also the curtailment of foreign assignments as a result.”

NPR:

“By the time I read about Marina Menegazzo and María José Coni, their bodies have already been found. They’d been missing for nearly a week and were discovered on Feb. 28, wrapped in plastic bags and dumped near a beach in Ecuador. One had her skull bashed in, the other had stab wounds and had bled to death. The two Argentine tourists, 22 and 23, had been vacationing in Ecuador. Their murder wasn’t reported much in English language media.

As is often the case with crime in Latin America, there’s been an array of versions of what happened shrouded in a cloud of doubt. Initially, Ecuadoran authorities detained two suspects and said one had confessed that he and his friend were drunk. One of them tried to touch one of the girls and she resisted. He then hit her on the head with a stick; the blow killed her. The suspect says her friend panicked, and the other murder suspect stabbed her.The families of the victims publicly questioned this version — they think both suspects might have had nothing to do with the murders and were being forced by authorities to confess.

In recent days another version of the story has surfaced: One of the suspects has linked the murders to a group of Colombian, Ecuadoran and Venezuelan drug traffickers, one of whom was arrested this week. Coni’s father has publicly speculated that “perhaps they kidnapped the girls to traffic them and killed them.” The Argentine Consul in Guayaquil, Ecuador, has said he does not discount that hypothesis.

Justicia por Marina Menegazzo y María José Coni!! pic.twitter.com/neUkxWYjFD

— Milagros Portioli (@Mili_Portioli) March 3, 2016

One thing is for sure: The murders have sparked outrage in Latin America, where there is a widespread crisis of femicide (the deliberate killing of women) and sexual violence. Central America has some of the highest rates. The 2012 Small Arms Survey, often cited by United Nations, surveyed murders of women around the world in the years 2004-2009. At a rate of 12 per 100,000, El Salvador is the country with the highest femicide rate, followed by Jamaica (10.9), Guatemala (9.7) and South Africa (9.6). Many of the deaths are related to gang violence that rages throughout much of Central America: In a recent series, NPR investigated the brutal effect gang violence has on young women, who are seen as sexual trophies and are targeted in sexual attacks.

Central American women who choose to leave the region and head north to the U.S. face a grim reality. Amnesty International estimates that 60 percent will be assaulted on the way. Activists report that many take birth control before the dangerous journey, in preparation for possible sexual assault.

And it’s a problem that extends far south. According to Argentine NGO “La Casa Del Encuentro” in 2014 nearly 300 murders in Argentina were considered hate crimes against women. All of this has led to a growing women’s rights movement, with the hashtag campaign #niunamenos (#notoneless) protesting the killing of women. It’s also led to femicide laws in several Latin American countries, including in Brazil, where the U.N. estimates that an average of 15 women a day are murdered in acts of gender violence. The new Brazilian law imposes jail sentences of up to 30 years for convicted offenders and longer sentences for criminals who attack girls under 14, women over 60 and pregnant women.

The outrage over the fate of the Argentine tourists goes beyond the killing itself. News articles about the murders are filled with reader comments like this one: “It’s terrible, what happened to them, but how irresponsible of their parents to let them travel alone, backpacking.” Another commenter writes: “the world is tough and their parents clearly didn’t teach them well … What did they expect?”

That line of questioning has launched a twitter hasthag #yoviajosola (#Itravelalone).”

There SHOULD be outrage. No woman should be killed simply for being female in public. Or for simply being female. (And ideally, no one should be murdered, period!).

When people have warned me to not travel someplace because it’s unsafe, I weigh the facts. I’ve never not gone somewhere, but twice I did adjust my plans. When I went to Egypt, I decided I’d feel safer with my dad. When I went to India for a conference and sightseeing, I decided I’d feel safer going with a friend than alone.

But generally, I realize that I have just as much chance of being street harassed near home (as I was earlier this month) as I do abroad or in other states. And it’s more likely that I’ll be hurt in a car accident here at home than that I’ll be raped while traveling.

So yes, harassment and worse are considerations, but they won’t stop me from traveling for work, for activism, and for my own education of the world.

We should not blame women who are traveling alone or with other women for the harassment or violence they face. We should instead do everything that we can to ensure that everyone can have the freedom to navigate our world safely, in their own communities and abroad.