This article has been cross-posted from Kaligraphy Magazine for International Anti-Street Harassment Week. You can read more stories about street harassment in Spain at Levanta La Voz! Madrid.

I started this webzine because I believe in the power of story sharing; in raising awareness, in connecting people, in promoting empathy, story sharing is one of the most powerful tools at humanity’s disposal for effecting change.

I started this webzine because I believe in the power of story sharing; in raising awareness, in connecting people, in promoting empathy, story sharing is one of the most powerful tools at humanity’s disposal for effecting change.

This is understood by Hollaback, a global network founded in 2005 of activists committed to ending street harassment largely via story sharing and mapping on their app and website.

Last year, I helped found one of these networks in Madrid, Spain, after I met an expat like me who was appalled by the pervasiveness of street harassment worldwide. With myself and five other strong, committed women, we founded Levanta La Voz! Madrid to help women in Spain’s capital find the support they need through sharing their stories.

Here are our stories.

Elena

67% of girls experience harassment before age 10. I was one of them.

When it happens to you at such a young age, it becomes a part of you. You get used to it, in a way, but you never stop being vulnerable. You flinch every time a male stranger talks to you, conditioned to expect harassment. You put up walls in the way you walk and the way you look, which often only elicits more harassment: “sonríete!” (smile).

So when I first moved to Madrid, I wondered if it would be different. After living there no more than a few weeks, I attended an event hosted by a group that showed films which passed the Bechdel test. After the film, I asked the group’s founder, a woman from England, what her experience of street harassment was like in Spain compared to back home. She directed me to another woman at the event, Debbie, who she said was interested in starting an organization to target that sort of thing.

Bingo! I love activism. Debbie and I talked, and I was immediately on board.

My personal experience of street harassment in Spain differs in some ways from that of the co-founders. I’m a short, curly-haired brunette who fits perfectly well with the description of a “typical” Spanish woman. In other words, I fit in.

In my view, street harassment in Spain centers largely on targeting the ‘other’, reminding those who don’t fit in that they don’t belong – exoticizing them, which is never a good thing.

But even though I’ve rarely had more than the occasional, uncomfortable “oye, guapa!” thrown my way, I’m still conscious of the culture of power and domination which exists as profoundly here as it does in the United States. And as long as it exists, I’ll be fighting to ensure it doesn’t.

Kate

I had been living in Madrid for a while and looking to be more involved with the local community and feminist activism.

Street harassment had been something I struggled with here since the beginning.

Whilst my home city, Brisbane, also has street harassment, it was usually people yelling things at me from cars or on public transport; whereas, here more often than not my harasser would be literally centimetres away – or less when they reached out and touched me!

As with most places in the world men especially target people that look different to the “typical” Spanish person. Hence, being blonde acts as a beacon for street harassment, ¡ya, yo sé que soy rubia!

I’d tried a few strategies for dealing with the street harassment – venting online and to my friends, doing something “daring” when it felt safe to do so – like giving them the finger as I walked away, or with one man who was in his 80s, I practically pushed him over.

Most the time the street harassment I’ve experienced has been on the annoying side rather than scary but not always.

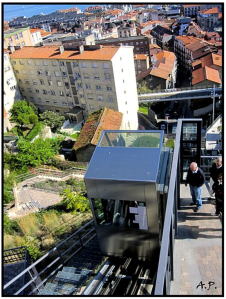

When I’d been in Spain for just two weeks, I was taking Spanish classes in Santander, Cantabria. One Sunday morning, I was walking down from my host family to meet my boyfriend in centre of the town. Now Santander has a lift that you can take to get from the top to the bottom of the town. To get to the lift I had to walk next to an empty construction site. As I walking along, a man behind me called out “Hola guapa!” Not wanting to engage with him, I walked a bit faster and ignored him. He was furious, he called out after me “Oye, puta” and started running towards me. There were several flights of stairs next to the lift so I ran down a flight and decided he would either take the lift and I could go back to the top or if he started coming down the stairs towards me I would have a head start. He took the lift down and was out of sight. I waited awhile then walked down to the bottom of the stairs. It turned out the man was still waiting there and ran back up to start yelling at me. There was an old man waiting for the lift, so I stood beside him, hoping the other man would just go away. After a while, he moved away and walked up to a seat that looked over the lift and kept muttering things at me. I ran down the hill and met my boyfriend there. It was terrifying as the man just had so much rage, all because I’d ignored his “hola guapa” remark.

So earlier this year when I met a woman, who I now work with, who told me she was working with other women on a grassroots, community led response to street harassment, it couldn’t have been more perfect. I was being harassed daily and had had enough scary encounters to know it was a serious problem and one that left you feeling helpless and sometimes alone.

Jen

I moved to Madrid 2 years ago and I immediately began to notice that men would comment as I walked past. At first I wasn’t sure if I was imagining things. Then when it became more common I didn’t always understand what was being said and I certainly didn’t have the level of Spanish to retort. I felt frustrated and angry. I stopped making eye contact. I started listening to music all of the time when I was out and about so that my earphones would block out any harassment. I have since acquired a level of Spanish to tell my harassers off. Sometimes I just explain that I don’t like their behaviour and would like their respect. Sometimes I ask them if they think I am as insignificant to them as a dog. Thankfully I have never felt unsafe or threatened, but I panic if I leave my house without earphones, avoid certain streets and don’t make eye contact. I am also always mentally prepared with a comment. It affects how I feel at times depending on what I’m wearing. I am thankful the weather is cold again so that I don’t have any skin on display. The reason I got involved in Hollaback is because I don’t want to feel oppressed anymore and I envisage a future where no one feels like I do – regardless of sex, race, religion, sexual orientation, body type, ability, or age. We all have the power to try and make a change.

Debbie

Why did I get involved with fighting street harassment? Because I just couldn’t take it any more.

Harassment is something I think women notice and feel more when they live abroad. This leads me to believe that the prevalence and society’s normalisation of street harassment means women are more likely to think of their own country’s harassment as just part of being a woman, but it’s when we are abroad and experience another culture’s harassment that we really feel it.

So despite having experienced plenty of harassment in my native country of England the street harassment cultural shock I got from moving abroad to Spain was difficult to deal with. I hated it but as a young woman I knew that putting limits with complete strangers would get me called a ‘bitch’, ‘frigid’, ‘uptight’, ‘no fun’, ‘humourless’ and more. I tried to swallow it – it is of course, I thought, the price of being a woman. But years went by and as I got older I realised that, even though I’m a woman, I deserved a basic respect that was continuously being denied me in the street, and that’s when it got unbearable. That’s when I started noticing just how often it happened, started realising it had nothing to do with the clothes I wore, nothing to do with how I looked, realising that no matter how I reacted – angry, confused, polite, conversational, you name it – what I got back was aggression and all this led up to me one day running home, locking myself in and crying, wondering if my harasser might have followed me and now knew where I lived, and what he would do to me if he saw me again in the street. The power play became evident and I went online looking for support, support I desperately needed so I wouldn’t feel alone as if these things only happened to me.

What I found online is what has brought me to where I am now. I found that street harassment is a global problem, a cross-cultural problem, and that it happens to most women but that we simply don’t talk about it. I read up on it, worked through my own brainwashing and ideas of what it was and where it came from and I started talking about it with my friends only to find that almost all of them had silently been experiencing street harassment and felt just as I did. I wanted to do something about it and was so lucky to come across the section of Hollaback! which explains how they support anti-street harassment groups globally, and was so lucky again to end up forming a team with an amazing group of hardworking, dedicated women. Now we’re getting Madrid’s anti-street harassment movement off the ground and it’s the most exciting thing ever – the idea of a Madrid where women decide to stop and say ‘No. No more’ to street harassment.

Vicky

Within a few weeks of living in Madrid, I became aware that I was receiving a lot of attention from men on the street. The sounds of “oye rubia” seemed to follow me everywhere. I became tired of hearing it, although it didn’t really affect me. However, as my Spanish improved I started understanding more and more of the accompanying comments I would receive, and I started to become annoyed and angry with the situation. Not a week would go past where I didn’t have at least one particularly memorable experience, but I was frustrated by the responses I received from many of my Spanish friends when I told them my stories: “this is Spain, you have to get used to it”. “Why should I have to get used to this?” I asked my friends, and I asked myself.

I wanted to be able to change this attitude towards street harassment, so that people would realise it is a problem and not the way things have to be.

Being harassed became an expectation in my daily life. It affected how I now behave when I am out and about, causing me to always wear headphones so I’m more likely to be left alone as harassers don’t have the enjoyment of seeing their words register. I started mentally preparing myself if I was going out wearing more revealing clothing. It affected how I behaved with my partners in public, as even just holding hands with another girl can elicit stares and comments.

Having lived part of my life in a country where wearing “inappropriate clothing” in public would cause me to be arrested and my family to be deported, I really value the freedom to be in public spaces without fear of harassment, comments, judgement, or attack. By working with Levanta La Voz (Hollaback) Madrid, I hope to be able to bring this freedom to myself and to everybody, so that nobody fears being unsafe in a public space because of who they are or how they choose to present themselves.

Blanca

It was summer, I was on vacation at the beach with my family where we always went back then. It was 4 in the afternoon and my sister suggested going to the mall for the afternoon. It was a bit of a walk and although I was lazy I decided to accompany her. Five minutes after leaving the apartment we heard the honk of a car horn as the car passed by us. So my sister in turn proposed a new game: What if we count the times the cars honk at us or someone says something to us? It was more than ten cars which honked or said something to us, and two men who made some sort of comment. I was 13. My sister 16.

All my life I’ve experienced street harassment, and therefore all my life it was put into my head that it was something unique to men, and something inevitable for women. I had to be careful not to be harassed, assaulted, or potentially raped. All my life I’ve experienced the frustration of not being able to do anything against “what it means” to be a woman. “There are crazy men who you are going to know what they can do to you if you are careless. You have to take precautions and be careful.” That is what the world has taught me and all women since we were children.

All my life I assumed that these roles were established and I couldn’t do anything to change them, and that wasn’t the worst of all: It never occurred to me to think them over. But luckily they also made me see that a critical look and a thoughtful mind are the best form of liberty. And little by little that idea has kept me going until researching, self-analyzing, and seeing what is real and fair in everything around me. “Feminism ruined my life but also, and above all, it was my salvation and liberation.” For me, introducing myself to feminism and joining Hollaback was just that: liberty and empowerment. All my life I’ve experienced street harassment, and probably, and sadly, I will continue experiencing it, but never again will I let it silence me, shame me, and violate me. Now I can raise my voice, and make myself listen. And I can do it together with devoted, strong, and inspired women that work every day so that more than half of humanity can once again feel safe and free.

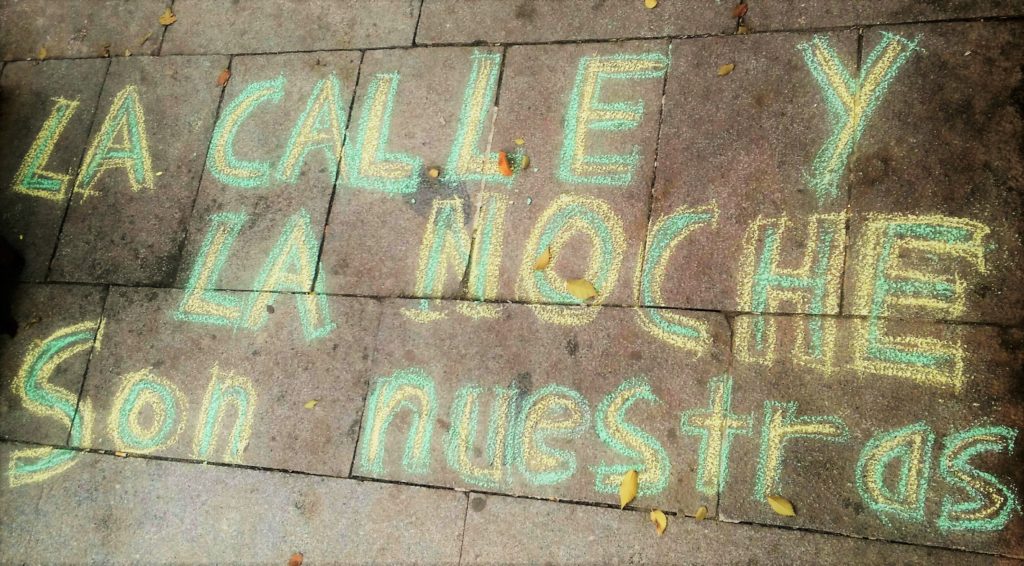

Photo by Levanta La Voz! Madrid.